Delia Burns

Since the outbreak of war in Tigray in November 2020, the Government of Ethiopia and its coalition partners have persistently obstructed humanitarian aid, pillaged and destroyed medical infrastructure and services, and incited violence against humanitarian workers. These actions have been well documented and are clear violations of international humanitarian law (IHL). Yet, the United Nations Security Council has failed to invoke resolution 2286, which was intended to prevent precisely such abuses against medical and humanitarian personnel and their activities, and seek accountability when they occurred. The UN Security Council met for the first time to consider the crisis in Ethiopia only this month. It has not condemned the systematic violations. Moreover, statements by UN Secretary General António Guterres have uniformly conveyed confidence in the assurances he has received from Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, most recently on July 9.

Resolution 2286 was adopted in May 2016, in the light of increasing violations against humanitarian staff and operations in armed conflicts. With special input from the International Committee of the Red Cross and Médecins Sans Frontières, the resolution drew upon disturbing patterns of violations in conflicts around the world including Afghanistan and Syria. In paragraph 1, the Security Council:

“Strongly condemns acts of violence, attacks and threats against the wounded and sick, medical personnel and humanitarian personnel exclusively engaged in medical duties, their means of transport and equipment, as well as hospitals and other medical facilities, and deplores the long-term consequences of such attacks for the civilian population and the health-care systems of the countries concerned.”

It calls for an end to such abuses and for accountability for perpetrators, and (in paragraph 12) requests the UN Secretary General to report to the Council,

“recording specific acts of violence against [humanitarian and medical personnel and facilities], remedial actions taken by parties to the armed conflict and other relevant actors, including humanitarian agencies, to prevent similar incidents, and actions taken to identify and hold accountable those who commit such acts.”

What might such a report contain? Here is an outline.

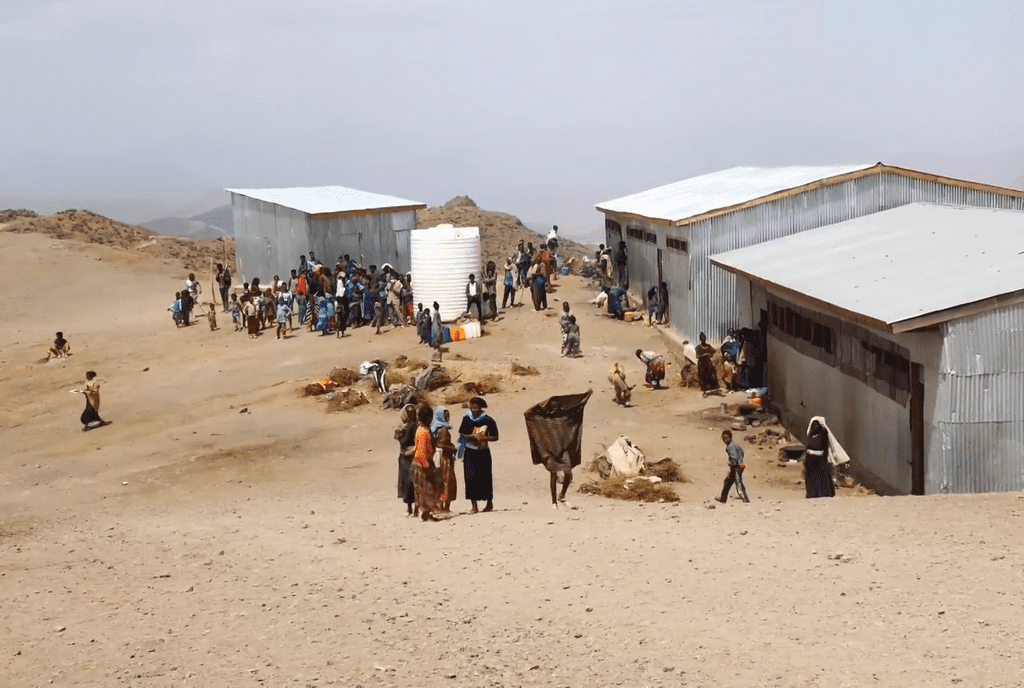

A conflict-induced humanitarian crisis

Approximately 5 million of 6 million people in Tigray are in need of emergency aid. As many as 900,000 are in conditions of famine. This is entirely the result of widespread pillage, destruction of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, and obstruction and diversion of humanitarian assistance over the last eight months.

When fighting began between the Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) and the forces of the regional government of Tigray on November 4,2020, aid convoys were blocked from entering Tigray for five weeks. Over the following seven months, The United Nation’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid (UNOCHA) has recorded over 130 incidents of agencies aid agencies being turned away at checkpoints and of staff being assaulted, interrogated or otherwise prevented from working in the region. With the murder of three MSF workers on June 26, the tally of aid workers killed in the conflict reached 13. This includes an employee of the Relief Society of Tigray, who was shot dead by Eritrean and Ethiopian soldiers in the central Kola Tembien district after declaring loudly that he was a humanitarian worker. The UN says that aid vehicles were still being turned away and aid workers assaulted and detained throughout the month of June. Notably, only one of 130 incidents of access violation prior to June was attributed to the Tigray Defence Force. The rest are attributed to members of the ENDF, allied Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF), and Amhara militia.

Tigray visit, Letmedhin Eyasu holds her son Zewila Gebru, 1 year old, who is suffering from malnutrition at Agbe Health center in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, on Monday, June 7, 2021. ©UNICEF Ethiopia/2020/Mulugeta Ayene (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

A situation update released by UNOCHA on July 1 paints a grim picture. Along with flights, road access remains mostly blocked – just one World Food Program convoy was able to proceed to Mekelle. Three bridges over the Tekeze river, connecting the Western Zone to the rest of Tigray, were destroyed, a serious blow to aid agencies who rely on the routes to access hundreds of thousands IDPs in need of emergency assistance. Partners report severe shortages of cash and fuel, and electricity and mobile network blackouts have severely hindered agencies’ ability to operate safely and effectively. Added to this, the killing of MSF staff members led to the evacuation of many humanitarian personnel from Abiy Addi, Axum, and Adigrat, some of the areas facing the most urgent need. In the wake of evacuations, much of service delivery has been halted. UN agencies themselves have been victim to attacks by armed elements, as Ethiopian soldiers stormed UNICEF offices during their withdrawal from Tigray capital, Mekelle, and confiscated vital satellite communication equipment. These acts amount to clear violations of the Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocols, which prohibit attacks on humanitarian personnel, equipment, and materials in both international and non-international armed conflicts.

A Devastated Health System

The Ethio-Eritrean coalition military campaign in Tigray ransacked and looted the great majority of the region’s medical facilities, leaving the population reliant on emergency medical assistance.

As early as January 2021, UNOCHA found that hundreds of health workers had fled to Mekelle and dozens of health centers had been looted by members of armed forces. Sometime in March, a medical student was raped by government soldiers inside Mekelle’s Ayder Referral Hospital. After the incident was reported, another 10 medical students came forward and recounted being raped by government soldiers. MSF reported an earlier attack on their staff that month, where one of their marked vehicles witnessed the summary execution of civilians by Ethiopian soldiers before their driver was beaten and instructed to return the staff to the capital. On May 16, Ethiopian soldiers raided the Axum University Teaching and Referral Hospital. Soldiers questioned patients, intimidated caretakers and threatened health workers, contaminated the operating room, and stopped all surgical operations in what appeared to be retribution for a CNN investigation and a search for pro-Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) fighters.

In and around the city of Adigrat, some 20 ambulances were taken from the hospital and nearby health centers and used for transporting looted goods by Eritrean forces. In the last month, the authorities blocked ambulances from reaching scores of victims of a deadly air strike in a busy market of Togoga.

Tigray: thousands flee in search of safety as humanitarian needs rise. EU humanitarian aid experts visited Wukro, a town 50km away from Mekelle, Ethiopia’s capital city. During the fighting in November 2020, the hospital in Wukro was damaged by shelling. It normally serves a population of 1.2 million people. © European Union, 2021 (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Resolution 2286 also calls on governments and armed actors to protect medical equipment, hospitals and other medical facilities. In February, nearly 80 percent of health facilities were inaccessible to humanitarian actors. In March, MSF announced that of 106 health facilities visited by MSF teams in Tigray from mid-December to early March, nearly 70 percent had been looted and more than 30 percent had been damaged. Only 13 percent were functioning normally. MSF found that hospitals and other medical facilities have been hit directly by Ethiopian and Eritrean airstrikes. They have also been set on fire after being looted and having their equipment destroyed. A health facility in Semema was looted twice by soldiers before being set on fire. In Debre Abay and Mai Kuhli, soldiers destroyed equipment, smashed doors and windows, and scattered medicine and patient files across floors in health centers. They also scrawled anti-Tigrayan graffiti on the walls. In Sebeya town, soldiers looted a health center. The same center’s delivery room was later destroyed by a rocket.

Ethiopian and Eritrean forces have converted previously functioning hospitals and medical facilities into military bases to house both weapons and personnel. Some have also been used to detain prisoners and to hold women and girls kept in sexual slavery. One fifth of facilities visited by MSF were occupied by soldiers. These included a facility in Mulugat, which Eritrean soldiers were using as a base at the time of visitation. Abiy Addi’s hospital was occupied by Ethiopian forces until early March, halting services to nearly half a million people.

Paragraph 1 of Resolution 2286 “deplores the long-term consequences of such attacks for the civilian population and the health-care systems of the countries concerned.” The above reality indicates that Tigray’s health system will require years of work and significant resources to rebuild. In the meantime, its citizenry will likely remain dependent on outside assistance for their medical care.

Denial and Accusation

The Ethiopian and Eritrean governments have ardently denied accusations that their armed forces had hindered aid efforts. In April, the prime minister’s office claimed to have delivered 70% of the aid in Tigray. In early June, Mitiku Kassa, head of Ethiopia’s National Disaster Risk Management Commission, which manages the government’s crisis response, accused the TPLF of attacking food trucks and aid personnel, but did not respond to a request for examples. He told reporters that more than 90% of people in Tigray had been provided aid. “We don’t have any food shortage,” he said.

Later in June, after the TDF began to score significant military victories, the federal narrative around the aid effort turned hostile. In the face of a famine warning by the world’s most widely accepted metric, Abiy repeatedly denied its existence. The prime minister told the BBC on June 11, “There is no hunger in Tigray, there is a problem in Tigray, and the government is capable of fixing that.” In an interview with Fana

News on June 22, Abiy extended his denial to suggest that famine relief was a tool used to fuel the TPLF. He explains,

“When the famine struck in 1984-1985, [the TPLF] called for the aid corridors to open. Then the forces who wanted the fall of the Derg regime went to the desert [i.e. the Sudan border] personally and supported it by providing strategy, finance, training, and weapons. It was after that the [TPLF] became strong and even able to control Shire for the first time in 1989.

“Now, the forces who came up with this idea, provide weapons to the TPLF that made the Derg regime fall, are not able to come up with a new idea…They want to use today the same tactic which they used 30 or 40 years ago.”

Two days later, MSF staff members, María Hernández, Tedros Gebremariam, and Yohannes Halefom, were killed while traveling between medical program locations. MSF assured that the three aid workers were engaged exclusively in medical and humanitarian activities, in alignment with international humanitarian law and in agreement with all parties.

The assertion of sinister action on the part of the international community reflects previous statements by Ethiopian and Eritrean foreign ministers that accuse the international community of leading a campaign against Ethiopia and conspiring with the TPLF. A report on the interview published in the Ethiopian Herald on June 25 said that Abiy also mentioned that aid agencies had declined a military escort he offered them, which he said further revealed their “hidden agenda.” For their part, aid agencies are often extremely reluctant to accept military escort, especially when those armed forces are suspected to have engaged in committing atrocities. A June 30 press statement released by the prime minister’s office lamented that the Ethiopian government had received little thanks from international donors for its efforts to deliver aid in Tigray. The PM also purports that people were registering multiple extra beneficiaries per household so that the extra support could be redirected to Tigrayan forces.

What Next for Aid in Tigray?

The stage of the war from November to June was characterized by widespread and systematic starvation crimes perpetrated by the forces of the Ethio-Eritrean coalition against civilians in Tigray and humanitarian and health workers and facilities. Following the defeat of the ENDF and the withdrawal of the EDF, these violations appear to have stopped.

What has followed instead is a siege of the approximately 6 million people living in Tigray under the control of the restored regional Government of Tigray.

Abiy’s June 30 statement claims he made a decision to leave Tigrayans to their own devices for a “time of reflection,” an apparent confirmation of the government’s intention to cut off civilians and agencies in Tigray from communications, access and services. Nevertheless, on July 9, the Government of Ethiopia released a statement on humanitarian flight arrangements to Tigray, which reiterates the untruth that the government has not denied any humanitarian flight request. The same statement condemns the “unconstructive actions” of UNOCHA and claims that the agency’s “inaccurate reports and statements” have not been helpful since the beginning of its “law enforcement operation” in Tigray. It goes on to accuse the agency of encouraging the TPLF, fueling misperception, and leading the international community to misconstrue the situation in the region. In a vitriolic end to the announcement, the government requests that the agency refrain from addressing the TPLF, whom the Ethiopian government has designated a terrorist organization, as the TDF, or else face “detrimental effects on the longstanding cooperation between the Ethiopian Government and the organization.”

The above denials, accusations and threats made by Prime Minister Abiy and his government are in violation of resolution 2286. They are both an incitement to additional violence against medical and humanitarian staff and their operations and facilities, and a clear statement of intent to commit further starvation crimes.

Delia Burns is an incoming second year MALD candidate at The Fletcher School, studying conflict and politics the Horn of Africa. Prior to Fletcher, she lived in South Sudan as a humanitarian worker with Action Against Hunger. There she helped to design and administer emergency nutrition, health, food security, and water and sanitation programs. She holds an bachelor’s degree in humanitarian affairs and political science from Fordham University. At Fletcher, she is a Research Assistant with the World Peace Foundation and Editor-in-Chief of the school’s academic journal, the Fletcher Forum of World Affairs.