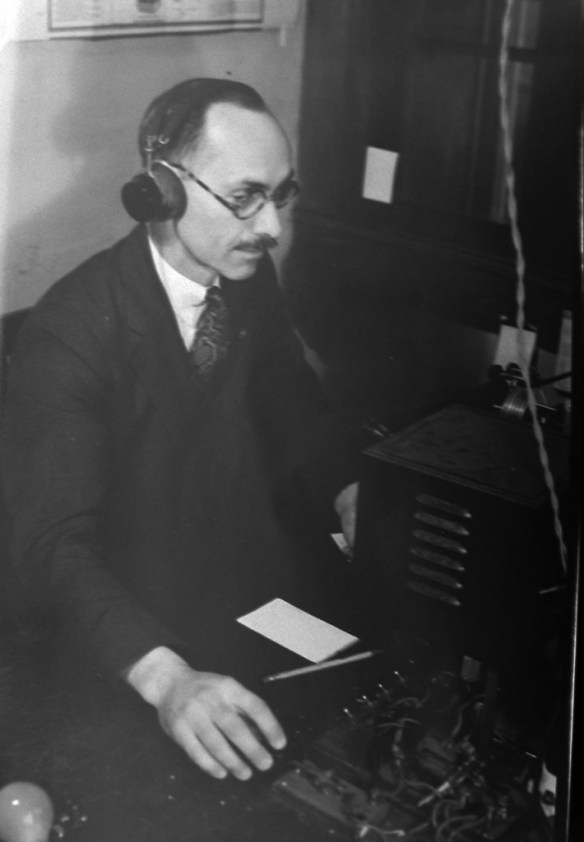

Ben Burtt in the studio

Starting as a humble film student at USC, Star Wars was audio enthusiast Ben Burtt’s first significant foray into the world of sound design. Working with George Lucas to give audio Lucas’ vision, Burtt was a pioneer of sound design as an art form. For its time, Star Wars’ sound was revolutionary: “there is more sound in that one picture than there is in ten average pictures put together” (Rinzler). While it’s difficult to attribute the massive success of Star Wars to any one element, the innovative sound design techniques Burtt used certainly helped.

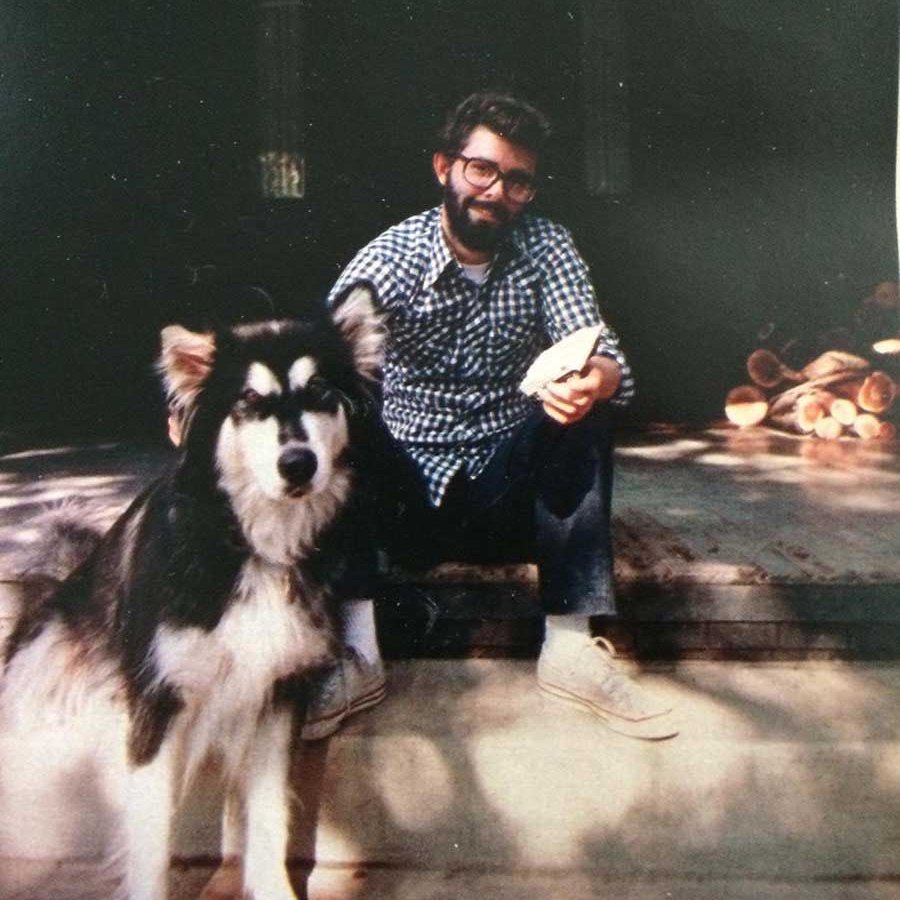

George Lucas and Ben Burtt

Inspirations

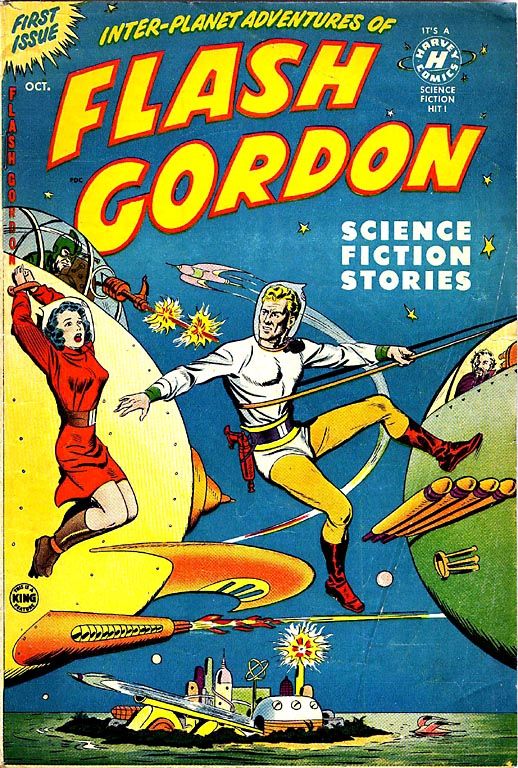

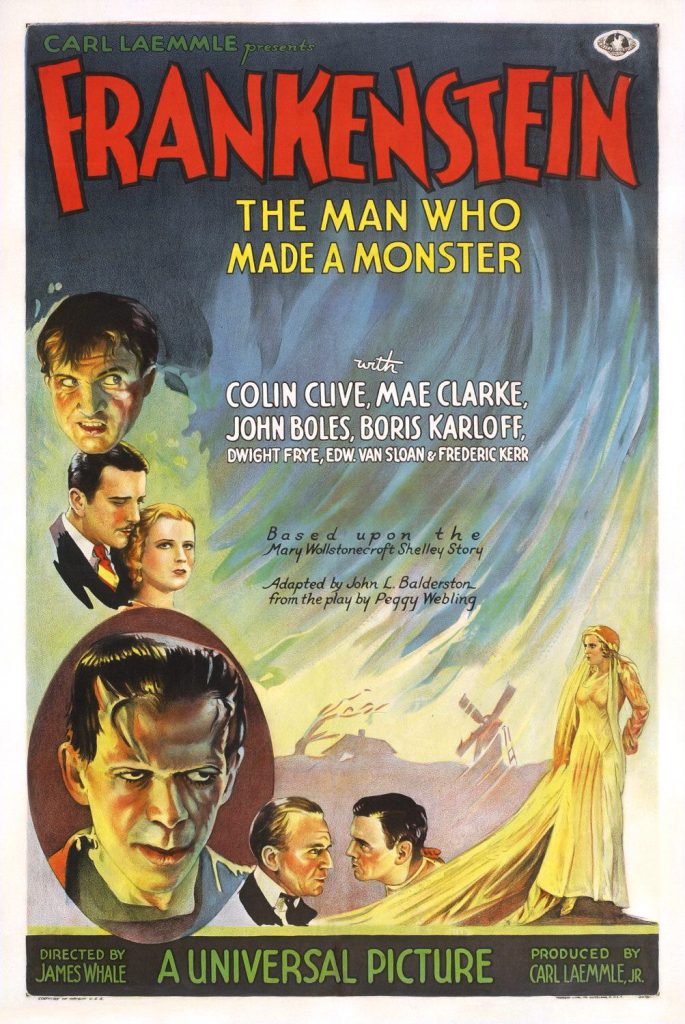

Decades before he’d even begun to work on Star Wars, classic Hollywood was influencing Burtt’s perception of sound. Burtt cites the 1931 Frankenstein movie, with its innovative electric and mechanical sounds, as being his greatest source of inspiration. Furthermore, many of the sounds from Frankenstein were later reused for the spaceships on Flash Gordon, from which much of Star Wars drew inspiration (Harvey). While working on Star Wars, Burtt reached out to the sound designer who had worked on Frankenstein, but he had become disillusioned with the movie industry. However, as Burtt recalls it, the sound designer’s faith in cinema was restored upon watching Star Wars, and he invited Burtt to get first-hand recordings of the machines he used to create the Frankenstein soundtrack. Though it was too late to incorporate Frankenstein’s sounds into Star Wars, they were used in the sound design for The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi (Burtt). After Frankenstein, Burtt credits the 1933 King Kong movie as another significant influence. Given the technological limitations of their era, the sound crew for King Kong had to be resourceful. Unable to bring their tape recorder to different locations, the sound designers had to create all their complex sounds in the studio. (Harvey). Though recording technology had since progressed to the point that portable tape recorders existed and anything could be recorded, Burtt retained the King Kong sound crew’s creative energy.

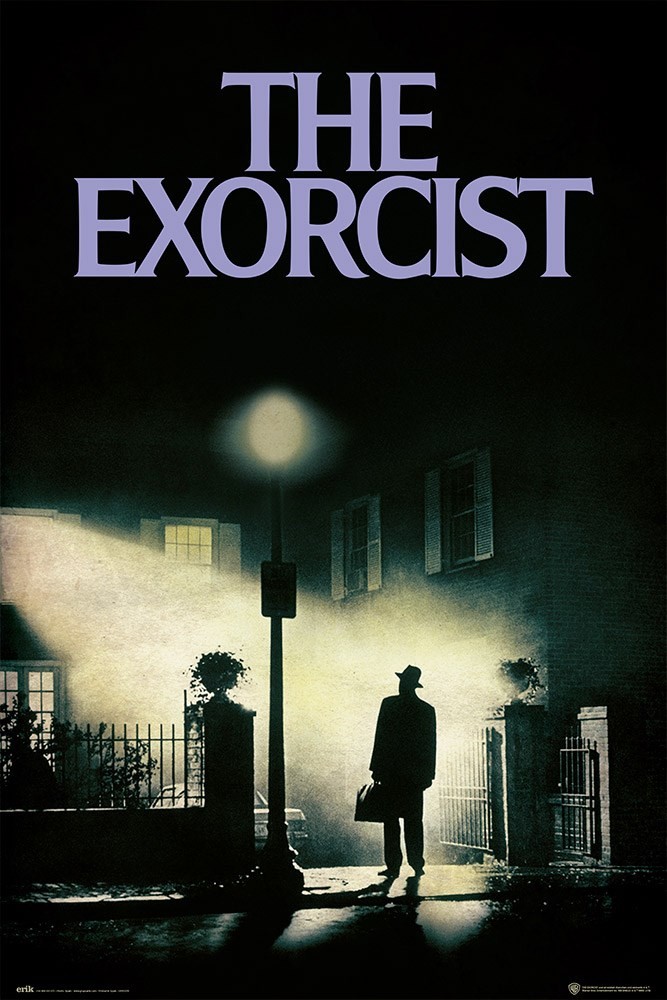

Burtt incorporated his love of classic cinema at multiple points throughout Star Wars. Several iconic sounds made cameos in Star Wars, like the now-infamous Wilhelm scream from Distant Drums, the Fox library thunderclap from a number of Fox properties, or the elephant howl from The Roots of Heaven: “I had the satisfaction of making use of some of the legacy left over from the great days of sound in Hollywood” (Rinzler). He has also directly credited movies like the Exorcist (Ratcliffe), Tarzan (Harvey), and Frankenstein (Rinzler) as the primary inspiration for specific sounds. To quote Burtt: “I felt comfortable with combining the alchemy of Chuck Jones with War of the Worlds, with Lawrence of Arabia. All of these films contributed to what I always refer to as the language of movie sound” (Harvey). This familiarity with the legacy of Hollywood sound provided Burtt a strong direction for his work on Star Wars.

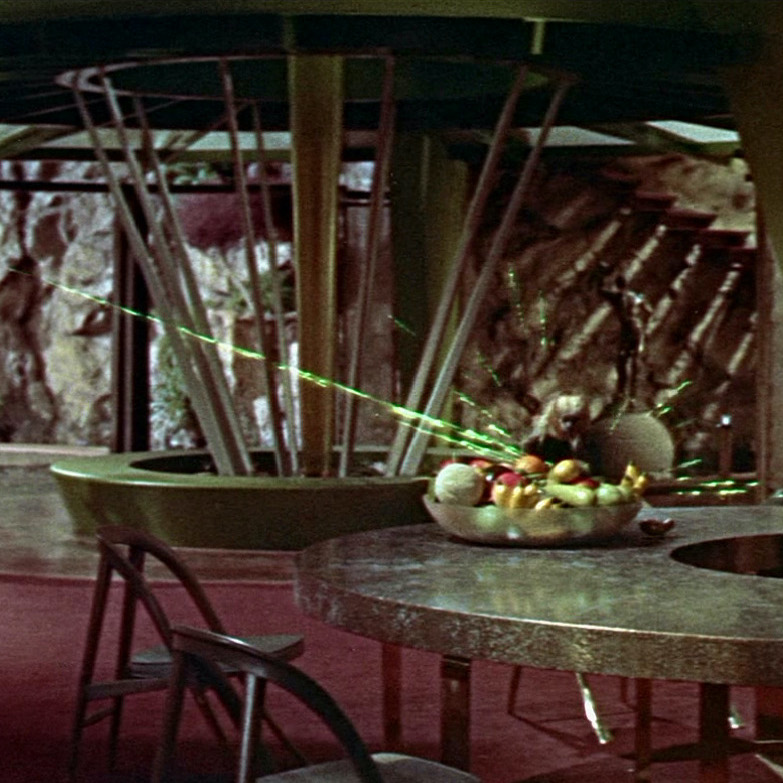

What usually comes to mind when thinking about the sounds of sci-fi movies is heavily synthesized electronic sounds: bleeps, bloops, and computer garble. However, in George Lucas’ quest to create a “lived-in” universe, he wanted to avoid the traditional electronic sounds, as “electronic sounds had been in a sense a cliché in science-fiction movies” (Rinzler).

Compare the sleek future envisioned in Forbidden Planet (left), to the grimy distant-past imagined by Star Wars (right).

With the exception of the film’s droids, who were actually very organically inspired, Burtt followed this central principle quite closely. Rather than over relying on synthesizer techniques, Burtt took unassuming everyday objects and recontextualized them to fit into the sonic universe of Star Wars. This approach was doubly useful: recording existing sounds was easier than programming elaborate synthesizers to approximate them, and listeners could form associations with the sounds on an instinctual level (Robertson). There was a significant artistic side to Burtt’s work; often the real sounds something made didn’t match its perception, so it was up to Burtt to recreate a sound’s perception: “that doesn’t mean I have to imitate those sounds. Often the sound you need is not the literal real sound, it’s something else. But, I love sounds that spring from real things” (DiCesare). In other cases, the object he was designing sound for didn’t exist at all, such as the lightsaber, so it was up to him to imagine and produce its reality.

Equipment

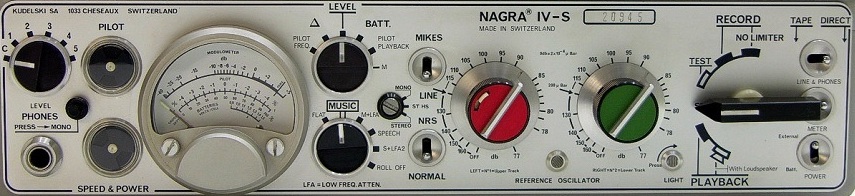

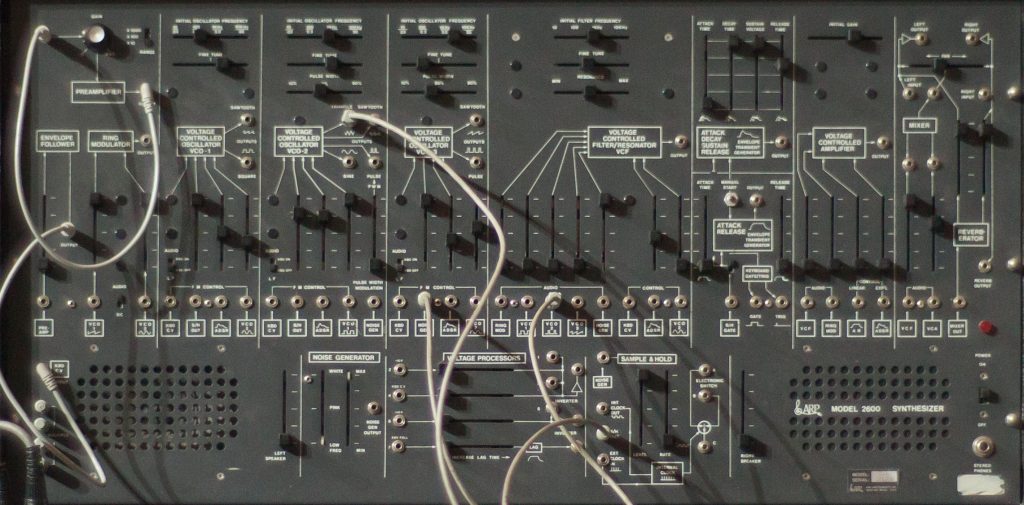

Compared to a modern musician’s vast arsenal of plugins and DAW’s, the tools Burtt had at his disposal to create the sounds of Star Wars were impressively minimal. The Nagra IV-S tape recorder—the only adequate portable stereo recording model at the time—was incredibly useful. Unlike the producers of King Kong, technology didn’t limit Burtt to the studio, so many of the sounds Burtt recorded came from unusual sources: from empty pools at zoos, to subway cars, to donkeys in Tunisia (Rinzler). Although only one microphone model, the small Sony ECM-50, has been directly catalogued in the tools Burtt used (Gallagher), images exist of him using other unidentified microphones. In addition to these traditional sound production devices, Burtt used the ARP 2600 and Moog synthesizers, the Eventide H910 Harmonizer to change track pitch while maintaining its speed, an Urei dip filter to clean up raw recordings, a graphic equalizer to adjust specific frequencies (Rinzler), and a Marshall Time Modulator to process vocal recordings (Calaitzis).

Telemetries

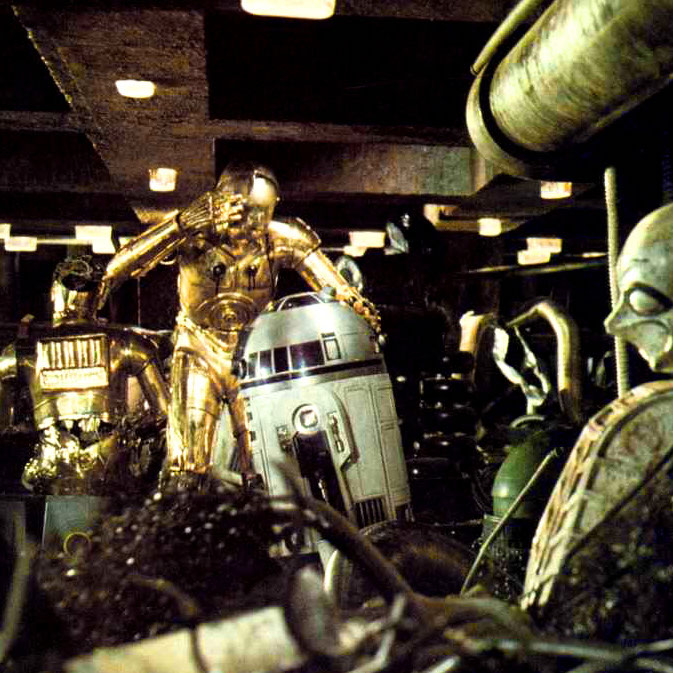

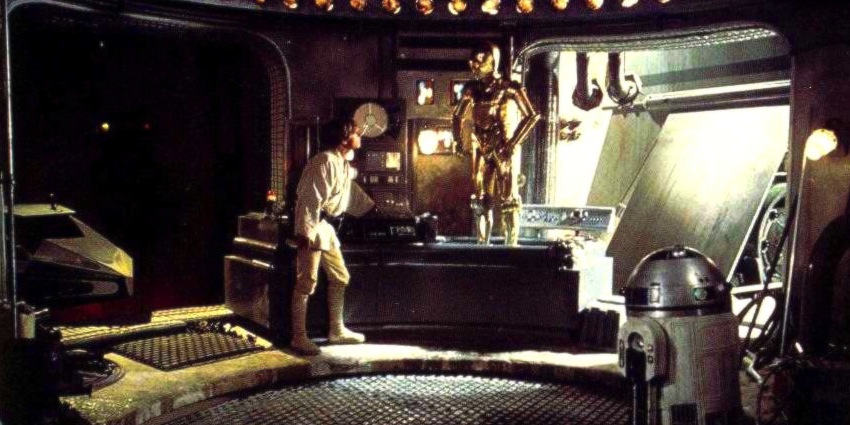

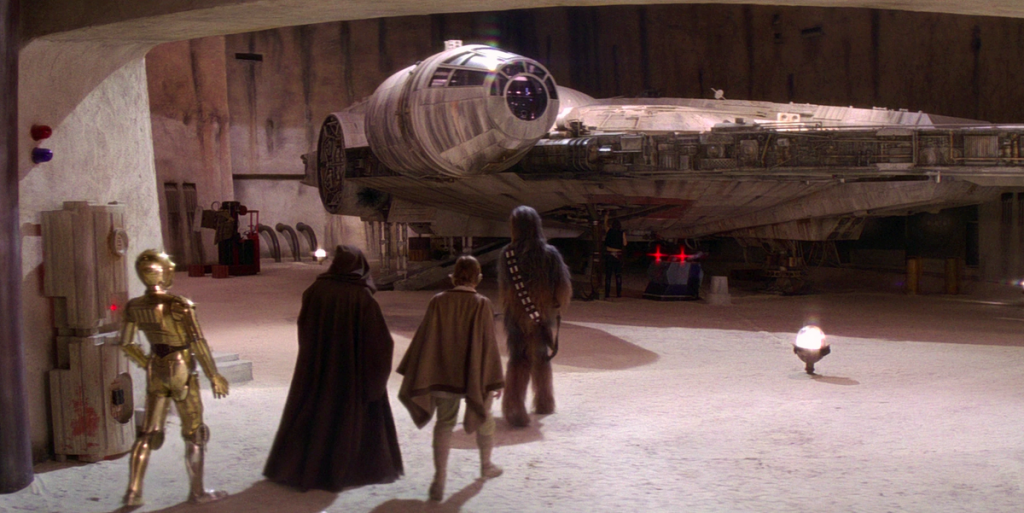

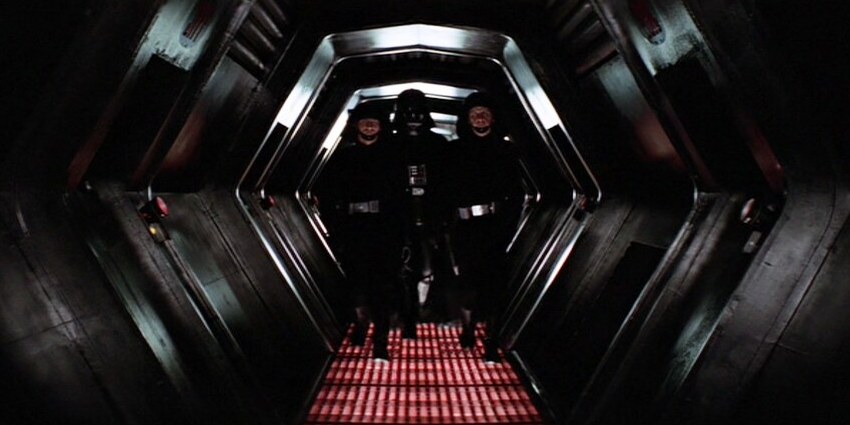

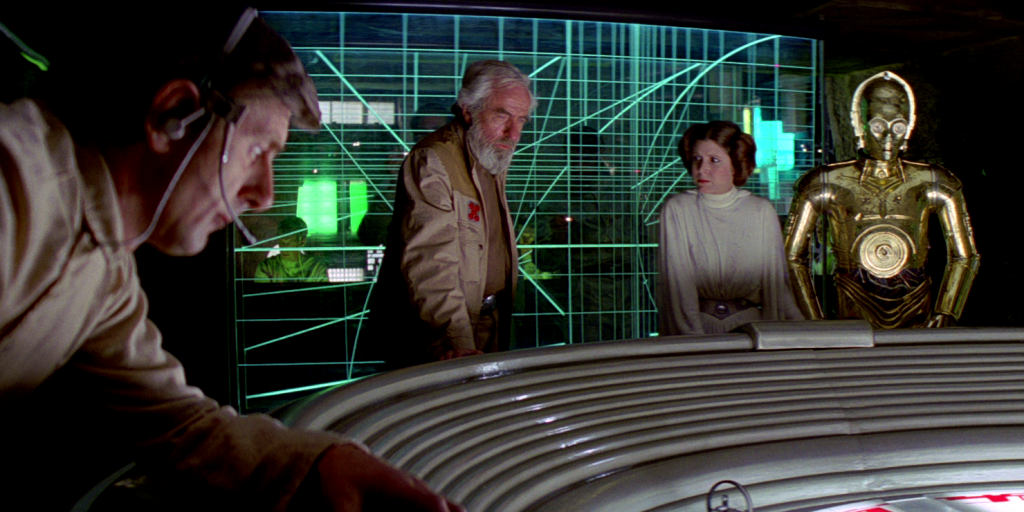

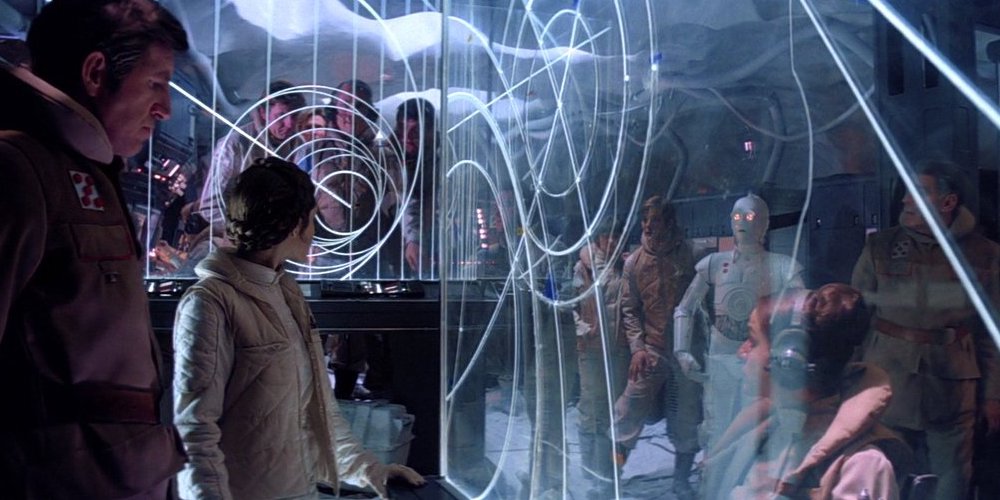

Many of the most fascinating sounds from Star Wars were the most subtle. The ambient sounds, or telemetry, as Burtt described it, were essential to creating a convincing universe. Several unique telemetries can be heard throughout Star Wars. On Tatooine, there are telemetries for the Lars homestead’s garage where C-3PO takes an oil bath [1], their kitchen and dining room [2], Obi-Wan Kenobi’s hut [3], and Docking Bay 94 [4]. The Death Star has a universal telemetry and low rhythmic pounding [5], as well as unique telemetries for the detention level [6] and the control room [7]. On Yavin IV, the rebel strategic center had multiple sounds [8].

The Lars Homestead Garage

The Lars Homestead Kitchen and Dining Room

Obi-Wan Kenobi’s Hut

Docking Bay 94

Death Star Corridors

The Death Star Detention Level

The Death Star Communications Room

The Rebel War Room on Yavin IV

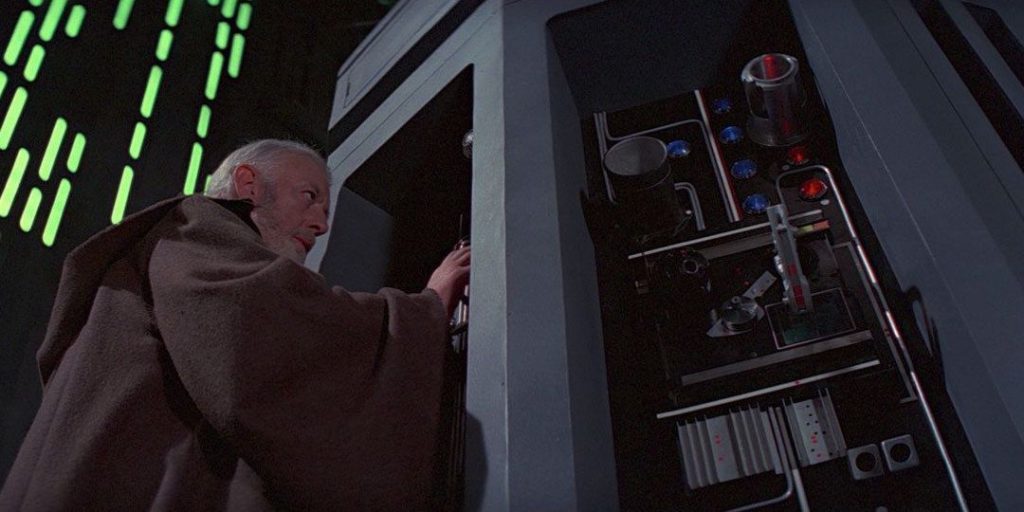

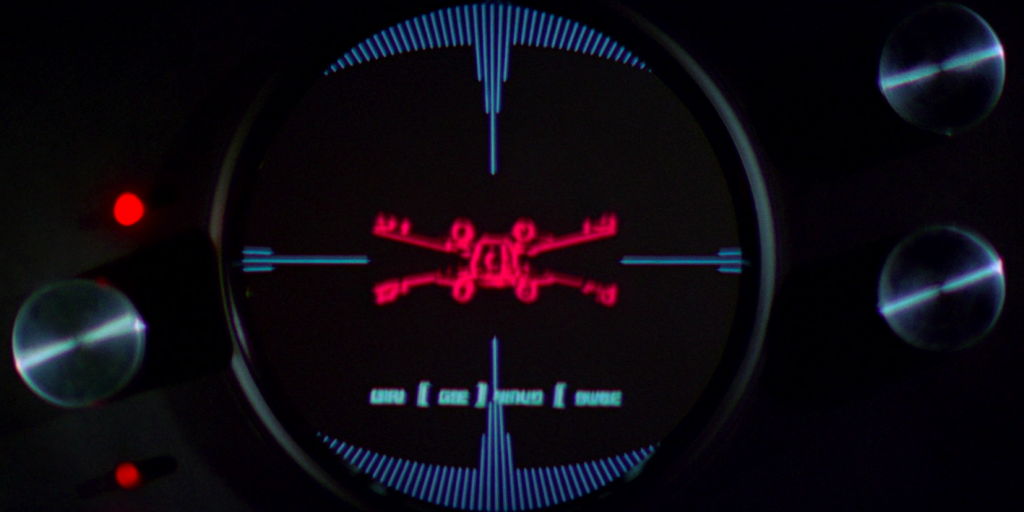

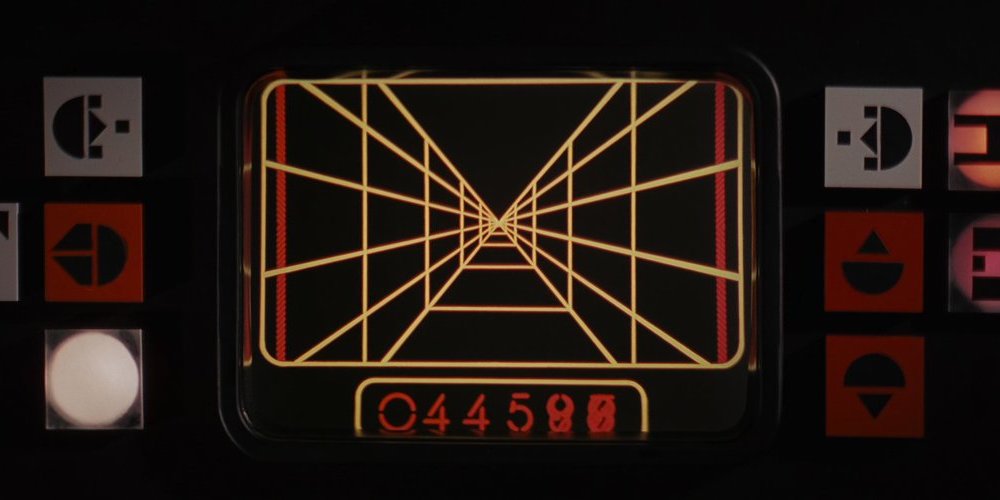

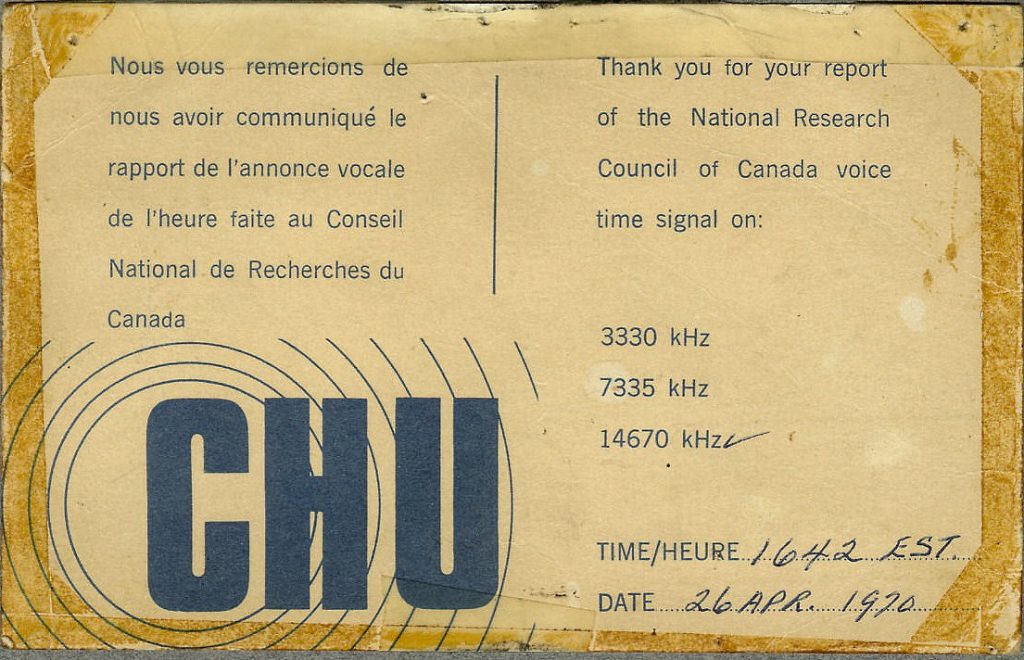

Most of these telemetry sounds were recorded by a teenage Burtt as he experimented with his grandfather’s 1930s short wave radio. He would play around with the tuning dial to find interesting sounds, record and tape-loop them, and then use basic tape manipulations to give them added depth (Gallagher). While the specific sources of each of these sounds remain unidentified, their origins can be postulated through extrapolation. Radio enthusiasts have confirmed that the data pips of Canadian time station CHU were recorded and manipulated to be the Echo Base telemetry [shorturl.at/mFY03] in The Empire Strikes Back (Thomas), while other devoted fans have identified the Death Star’s attack alarm as an altered recording of a ship’s horn from the 1953 film, Sailor of the King [shorturl.at/gnvI1]. To simulate loudspeaker announcements in both the rebel hangar and the Death Star hangar [9, 10], Burtt recorded himself delivering lines through a bullhorn in a large abandoned church, resulting in a natural echo (Gallagher). The hiss of airlock doors opening [11] came from recordings of doors closing on Philadelphia subway cars (Rinzler) and the opening of giant shutters at the Palomar Mountain Observatory. The motors of the Palomar telescope moving were used for other miscellaneous mechanical sounds (Gallagher). Other telemetries are clearly electronic, and could have been feasibly created on one of Burtt’s synthesizers. These include the descending pitch of a hum as Obi-Wan turns off the power to the tractor beam controls [12], the looped descending tone and sin wave LFO pitch-controlled tone of the Tantive IV’s alarm [13], the increasing frequency of the sin wave LFO pitch-controlled tone of the interrogation droid used to torture Princess Leia [14], and the targeting computers of the Millennium Falcon, X-wings and Y-wings, and Tie-Fighters [15, 16].

Echo Base Strategic Center

Death Star Alarm

Disabling the Death Star’s Tractor Beam

The IT-O Interrogation Droid

TIE Fighter Targeting Computer

X-Wing Targeting Computer

Millennium Falcon Turret Targeting Computer

Tantive IV Alarm

Rebel Hangar on Yavin IV

Death Star Docking Bay 327

Palomar Mountain Observatory, San Diego

Ben Burtt’s Grandfather With His Radio

During the assault on the Death Star, the rebel pilots communicate with each other and with their base via radios [8]. Inspired by old World War II movies, Burtt degraded the audio quality of the radio transmissions to increase their realism. By taking the original dialogue, transmitting it over a single sideband shortwave radio, and then recording the radio’s output, Burtt could faithfully recreate radio static. The strength of the effect could also be correlated to the relative distances of the radio; two pilots right next to each other would have very little interference, while officers at the base communicating to the pilots would have a lot more static and detuning due to the greater distance between them. Slightly mistuning the radio receiver was used to simulate natural fluctuations in radio interference. (Gallagher)

Characters

Designing R2-D2’s voice presented a unique difficulty—how do you make a robot emote and communicate to the audience, without facial features or any physical expression beyond turning its head? R2-D2 needed to be able to carry the first twenty minutes of the movie, communicate entire scenes without any dialogue, and convincingly interact with high-caliber actors like Sir Alec Guinness (Harvey). Drawing from cinematic history, Burtt modeled the concept for R2’s voice off of Cheetah, the chimpanzee from the original Tarzan movie, who Burtt noticed could “imply a great deal of intelligence with the character just with the sound” (Harvey).

Cheetah the Chimpanzee from Tarzan

Burtt began to toy around with the ARP 2600, though his first attempts at creating R2’s voice were largely unsuccessful: “the first I did were too electronic, pure synthesizer, too impersonal and cold. George wanted to add an emotional side to it” so R2 sounded like a “five-year-old kid” (Rinzler). The early drafts of R2’s voice can actually be heard in the final cut of the movie as the voices of all the other droids in the Jawa’s Sandcrawler [17] (Gallagher). To give R2-D2 an emotional side, Burtt connected a microphone to his ARP 2600 to control pitch, allowing the performance to be organically controlled. He would then come up with appropriate English dialogue for R2, and record himself speaking those lines while playing the ARP 2600. However, normal English intonations and inflections didn’t translate emotion very clearly to robotic language, and the idea of direct translation was mostly scrapped. There only appears to be one instance where the English dialogue was kept, where R2 can be clearly heard saying “at all?” to C-3PO [18]. The method Burtt landed on was abstracting what R2 was communicating to its fundamental emotion—excitement, fear, curiosity—and voicing those into the synthesizer: a sophisticated “baby talk” of whistling, cooing, sighing, and groaning (Rinzler). At certain points, this idea was taken even further, with the ARP 2600 outlining major chords to demonstrate happiness [19]. By making R2-D2’s performance “50% machine and 50% organic,” Burtt transformed a trashcan on wheels into a lovable yet mischievous character who could exist on its own (Burns).

After the process of designing and recording R2-D2’s voice had been completed, his voice needed to be mixed into the movie. However, the original tapes of R2 were too clean for the movie; they sounded like they came from a pristine recording studio, not the natural environments he was supposed to be in. Using a technique first developed by fellow sound editor Walter Murch for Lucas’ previous film, American Graffiti, Burtt played back the clean recordings of R2 in a number of different environments, and then recorded those sounds with another tape recorder (Rinzler). This process was called “worldizing” and was extremely useful for giving sounds a natural presence. As it turned out, this method was also much easier and more faithful than the alternative of using complex filters and synthesizers to approximate natural sonic phenomena (Gallagher).

Giving Chewbacca a voice posed a similar problem to R2-D2; how do you make a giant furry creature, with limited control of the facial prosthetics and who doesn’t speak English, demonstrate intelligence? As a secondary protagonist, Chewbacca’s emotions also needed to be multidimensional: going from “a giant teddy bear” at one moment, to “ferocious” the next (Rinzler).

Seeing as the inspiration for Chewbacca came from Lucas’ dog, Indiana, Lucas suggested that his voice be somewhat canine– after all, dogs could express themselves through whining, barking, growling, and so forth. On his quest to create Chewbacca’s voice, Burtt recorded dogs, bears, lions, tigers, walruses, seals, sea lions, camels, elephants, donkeys—practically the whole animal kingdom. The final iteration of Chewbacca’s voice was a mix of a walrus named Petula from the California Marineland, and a cinnamon bear named Pooh from Tehachapi, California (Rinzler). The editing process for Chewbacca was different from R2-D2’s, in that Burtt couldn’t necessarily direct a walrus to sound cute or angry. Instead, he had to first organize and catalogue the sounds by the emotional units the animal happened to give, and then stitch and assemble those into emotionally coherent phrases (Burns). Just as with R2, the recordings of Chewbacca were worldized to match the environments when mixing into the film. Though the specifics of what Chewbacca was communicating might not have been evident, the general intention still came through.

George Lucas and His Alaskan Marmalute, Indiana

Ben Burtt Recording Petula the Walrus

Ben Burtt Recording Pooh the Bear

Just as the failed voices of R2-D2 eventually reappeared as the voices of other droids, the unused Chewbacca recordings were used for other animal-like aliens. Petula the walrus also gave the voice of the walrus-like amputee in the cantina who didn’t like Luke, Ponda Baba [20] (Gallagher). The grumbling of Banthas [21], the large creatures the Tusken Raiders rode on, were made from slowed-down leftover bear sounds for Chewbacca (de Lange). The chatter of the cantina [20] was composed of dogs growling, bats squeaking, and early drafts of Jawaese. While filming the Tatooine scenes in Tunisia, the production crew used mules to carry the heavy equipment. The sound of the mules braying served as inspiration for the Tusken Raiders [22], which was a mix of real mules and somebody imitating them (Gallagher).

Mules On the Set of Star Wars

Tusken Raider Attacking Luke Skywalker

A Tusken Raider on a Bantha

Ponda Baba

Figrin D’an and the Modal Nodes, more commonly known as the Cantina Band [23], were meant to be an alien interpretation of “some 1930‘s Benny Goodman swing band music in a time capsule or under a rock someplace” (Williams). To create the diegetic “Jizz” genre of music, composer John Williams combined the traditional swing music sound of saxophones, clarinets, and trumpets, with more unusual instruments to create the uncanny effect. Steel drums were featured prominently in the melody, a Fender Rhodes comped chords, and an ARP 2600 was programmed to play the funky walking bass lines. Williams mixed the instruments to sound vaguely familiar, but still impalpably alien– clipping, attenuating, and then reverbing the low end to “thin out” the sound (Williams).

Figrin D’an and the Modal Nodes

Benny Goodman and His Band

Since C-3PO’s clunky plastic suit made too much noise on set to keep any of the original dialogue, all of the lines had to be re-recorded in a studio by Anthony Daniels (Gallagher). While Burtt hasn’t made any comments on how he processed Daniels’ performance, it’s believed that a phaser was used to make Daniels’ voice more electronic (Phaser). Other audio enthusiasts have suggested it was done by an using Eventide H910 Harmonizer (Gearslutz.com) which is a reasonable theory, given that Burtt has confirmed he used the H910 on Star Wars (Rinzler). To create the sound of C-3PO’s servo motors moving his arms, Burtt had originally used old metal ice cube trays that would make a metal rattling sound when shaken (Burtt). Due to time constraints, however, Burtt had to pass off the responsibility of creating the servo motor sounds to supervising sound editor Sam Shaw. Shaw, who was also responsible for creating R2-D2’s servo motor sounds, unfortunately didn’t create any records of how he made those sounds (Rinzler).

Ben Burtt Demonstrating the Metal Ice Cube Trays

Perhaps the most recognizable design of Burtt’s career is Darth Vader’s respirator. To find the sound, Burtt went to a scuba shop and recorded himself breathing “through Aqua-Lungs and through tubes, trying to find the one that had the right sort of mechanical sound” (Rinzler). From about eighteen unique breathing sounds, eventually the right one was found. By pressurizing a scuba regulator on a tank (Burtt) and putting a Sony ECM-50 (Gallagher) inside the valve, Burtt got the “clicking and clacking” of the valve that became Vader’s voice (Burtt). Though the importance of James Earl Jones’ performance can’t be overstated, it was further improved by electronic manipulation. Jones’ voice was reverberated and processed on a Marshall Time Modulator, a voltage-controlled analog delay instrument, to give Vader’s voice a robotic undertone (Calaitzis). The processed recordings of Jones were then worldized to give a natural presence (Rinzler). The low rumble of Darth Vader force choking Admiral Motti for his disturbing lack of faith was created by a mixing low-pass filtered recording of thunder after the initial clap with a slowed-down missile launching. (Gallagher)

Scuba Regulator -Find specific name

Darth Vader Force Choking Admiral Motti

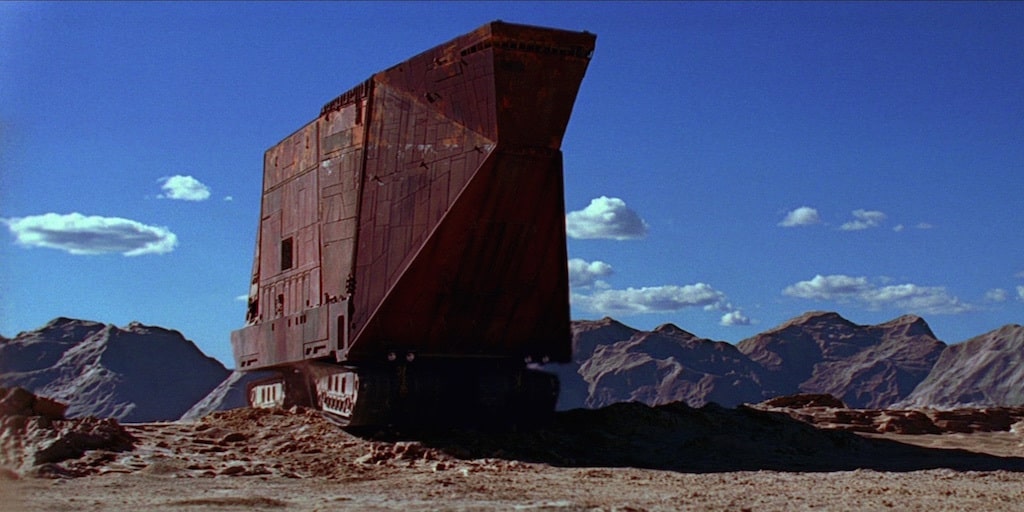

On the same day that Jones recorded his lines as Vader, the lines for Greedo [24] were recorded. Greedo’s voice went through multiple stages of development, beginning with a repetition of “oink-oink” into broken equipment. However, the result wasn’t nearly convincing enough to pass as a real language. To address this issue, Burtt collaborated with Larry Ward, a UC Berkeley graduate student and linguist (Rinzler). To give him a convincingly authentic alien sound without inventing an entire language, Ward used the Quechuan languages of Peru as inspiration for his performance (Gallagher). The audio was phased and flanged, likely with the same instrument as C-3PO’s voice, and worldized (Rinzler). Similar to Greedo’s Quechuan origins, the Jawa’s language [25] was largely inspired by the South African Zulu language (Gallagher). By speeding up recordings of his friends speaking and shouting phrases in Zulu and other African dialects, Burtt achieved the sing-songy quality of Jawaese (Rinzler). The Jawa’s vehicle, the Sandcrawler [26], got its sound from the clatter of Philadelphia subway (Rinzler).

Greedo

Jawas

The Jawas’ Sandcrawler

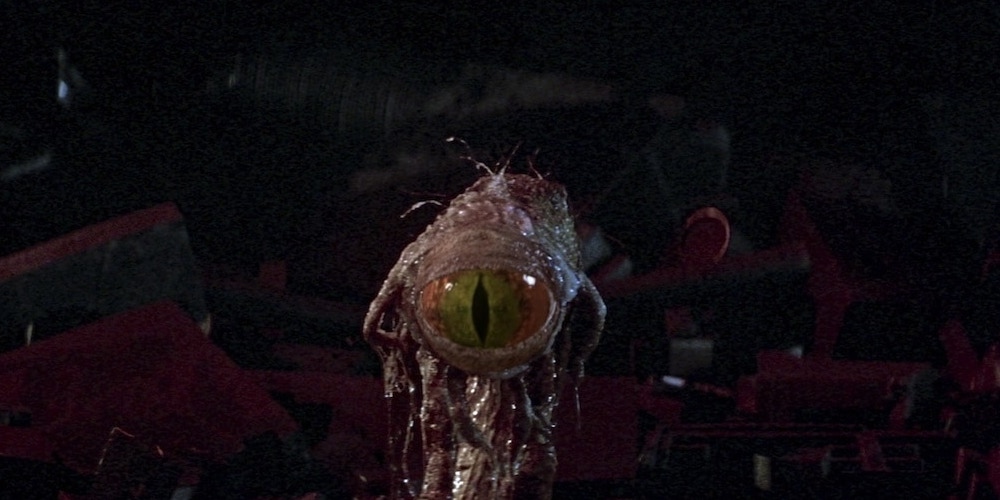

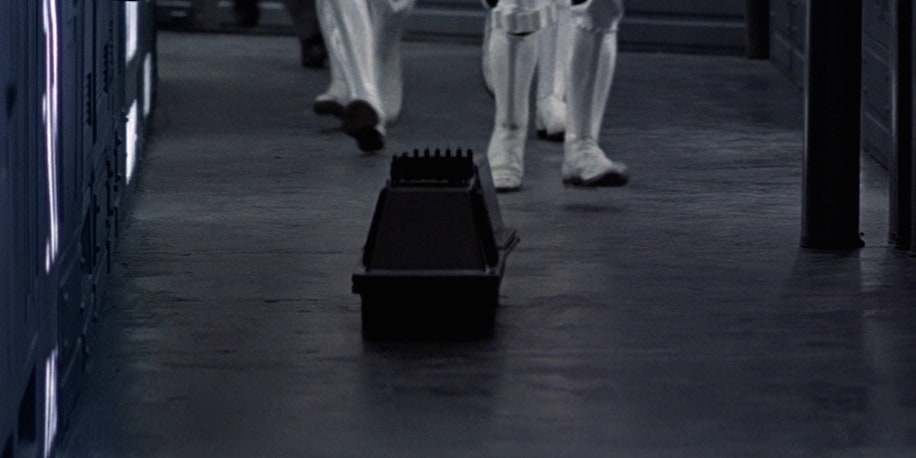

Garindan, the imperial spy on Tatooine [27], was voiced by the arguably most famous actor in the entire movie, John Wayne. Though Burtt didn’t realize it at the time, he took a random tape from the trash of John Wayne delivering lines for other movies, like “all right, what are you doin’ in this town,” and fed it into a synthesizer. The dialogue was then processed to complete abstraction through a series of random filters (Unnamed). Dejarik, the game which R2-D2 and C-3PO play with Chewbacca aboard the Millennium Falcon [28], was created playing recordings of Burtt vocalizing through a filter to sound tiny, and then tape splicing sounds together. Similarly, the aptly named mouse droids seen populating the hallways of the Death Star [29] got their mousey sound by speeding up and heavily filtering tapes of Burtt doing expressive vocalizations (Gallagher). For the voice of the Dianoga—the trash compactor monster [30]—Burtt drew inspiration from the voice of the devil in The Exorcist. Using a ring modulator, which multiplies two signals to create two new frequencies, on audio of himself moaning, and then adding echo to match the echo of the trash compactor room, Burtt created the Dianoga’s sinister roar (Ratcliffe).

The Trash Compactor Dianoga

Mouse Droid

Dejarik

Garindan Talking To a Sandtrooper

Weapons and Ships

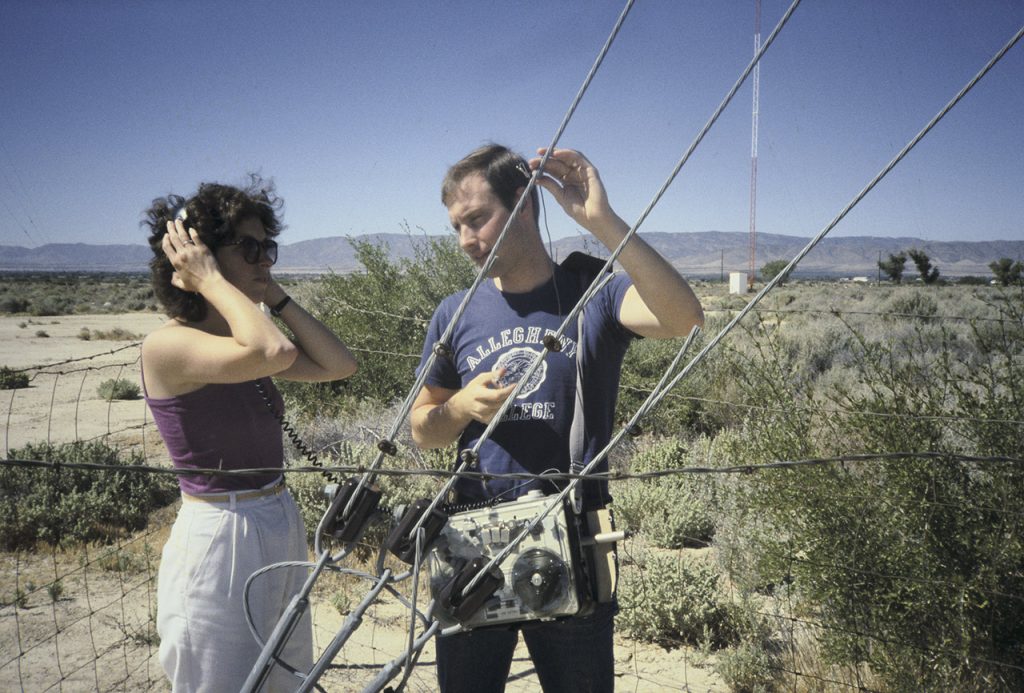

To get the sounds of the explosions of Star Wars, Burtt began at an unsurprising location: the gunnery range in the Mojave Desert. From there, he recorded rockets blasting off, gunshots, and miscellaneous explosives. Other explosions were created with legacy sounds, like the Fox library thunderclap. While the Fox thunderclap recording was itself a mix of thunder and someone hitting sheet metal, Burtt mixed it in with his own recordings of explosions to add depth. The thunderclap was used as the basis of the sound of the stormtroopers breaching the hatch of the Tantive IV [31], as well as many of the explosions during the assault on the Death Star [8] (Rinzler). To develop the sounds of the blaster rifles, Burtt collaborated with a gun collector, recording everything from black powder guns to M16 rifles. Basic shots were recorded, and a microphone was placed near the targets to capture the ricochets, which can be heard as Han tries to shoot the door in the trash compactor [32] (Rinzler). A product of random chance, Burtt discovered while hiking that hitting the support cables of radio towers produced a twangy laser-like sound. After much searching, he found the best sound came from a using a hammer to hit the cable of a radio tower on Mount Wilson in Los Angeles. After a few days of recording, he’d collected “a whole orchestra” of the distinctive laser sounds. By mixing in the twangy sound of the wire with bazookas and some of the other explosives he’d recorded, he created the basis for all the blaster sounds. (Rinzler).

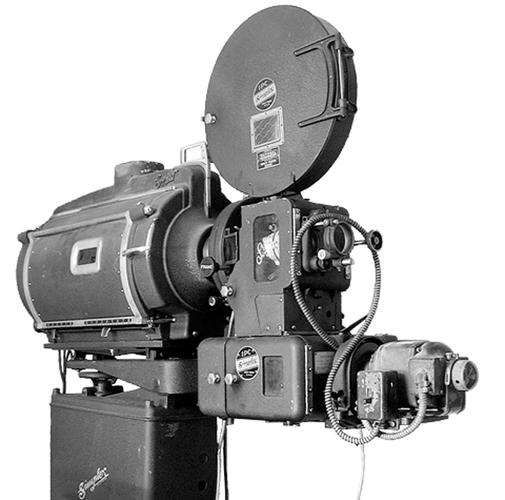

Originally a projectionist at USC, Burtt spent much of his time around theater projectors. When tasked with creating a sound for the lightsaber, he started by recording the idling interlock motors of a 35mm Simplex theater projector he worked with. Though he liked the sound, he recognized it was still missing something. As he was dragging a stripped microphone cable behind a cathode ray tube television, the tubes induced an aggressive buzz into the recorder by chance. The cathode tube buzz was mixed with the projector hum to get the basic lightsaber sound (Harvey). To add a sense dynamism to the lightsabers, Burtt used a modified version of worldizing. By playing the clean sound through a speaker and waving a shotgun microphone in front of speaker to induce the doppler effect, an auditory illusion of movement was created. For the ignition of a lightsaber and bigger clashes, Burtt recorded dry ice reacting with metals, and he used the sound of sparking carbon arcs being ignited in the studio’s lamps as smaller lightsaber hits, once again inspired by his surroundings (Gallagher).

35 mm Simplex Theater Projector

The sounds of most the vehicles’ engines came from the Pacific Airmotive wind tunnel, a jet engine manufacturer and testing site in Burbank. By securing a microphone to the wind tunnel and wrapping it with a towel to muffle the aggressive high-end, Burtt recorded the sounds of everything from Boeing 747s to small helicopter engines (Rinzler). The sound of Luke’s X-34 Landspeeder idling and accelerating [33] came from the reverse thrusters of an airplane engine slowing down in the wind tunnel. This sound was mixed with the Los Angeles freeway recorded through a vacuum cleaner tube on top of a microphone, which became the sound of levitation and force fields (Gallagher). The sound of the Imperial I-Class Star Destroyer [34] was a mix of an engine and the rumble of a broken air conditioner in Burtt’s motel room (StarWars.com). The main sound of the Millennium Falcon came from a slowed-down recording of a P-51 Mustang’s pistons, which Burtt recorded at an air show [35]. Whenever the Falcon flew by close to the camera, a lion roar and the Fox library thunderclap were mixed in to give it a more aggressive sound (de Lange). The sound of the Falcon jumping to hyperspace [36] was created by mixing an echoed Douglas DC-3 plane with the sound of the motion-control cameras used to film the miniatures (de Lange), the sound of an elevator motor starting up, and the Fox thunderclap (Gallagher). To create the sound of a TIE fighter [37], Burtt electronically slowed down and stretched out a Fox library recording of elephants howling (Rinzler) and mixed it with a recording of a car driving by on wet pavement (McGee). Incidentally, the sound of radio towers made a second appearance in the Star Wars. While hiking in the Poconos, Burtt heard the intense wind howling against the radio tower wires, creating a “minor key sustained note” which was used as the sound of the Y-wing’s interior during the attack on the Death Star [38] (Rinzler). To further help sell the sound, Burtt changed pitch of the recordings when cutting between ships [8] so that each ship had its own unique ambiance.

Douglas DC-3

P-51 Mustang

Though drawing his sounds from a wide variety of unlikely sources, Burtt used his creative sensibilities to make them coexist in the Star Wars sonic universe. His work on Star Wars served as inspiration for other sound designers, and it was ultimately recognized when he earned a Special Achievement Academy Award for his sound design. With Star Wars, Burtt proved that advanced technology and endless digital libraries weren’t essential to creating memorable sounds.

Works Cited

Burns, Kevin and Edith Becker, directors. Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy. www.disneyplus.com/movies/empire-of-dreams-the-story-of-the-star-wars-trilogy/. Accessed 2020.

Burtt, Ben, director. Discoveries From Inside: The Sounds Of Ben Burtt. www.disneyplus.com/movies/star-wars-a-new-hope-episode-iv/. Accessed 2020.

Calaitzis, Adam. “Marshall Time Modulator.” Toyland Recording Studio, 4 May 2018, toyland.com.au/marshall-time-modulator/.

de Lange, Sander. “From Concept to Screen: Banthas.” StarWars.com, 23 Sept. 2015, www.starwars.com/news/from-concept-to-screen-banthas.

de Lange, Sander. “From Concept to Screen: The Millennium Falcon.” StarWars.com, 15 Dec. 2015, www.starwars.com/news/from-concept-to-screen-the-millennium-falcon.

DiCesare, Ron. “Inside the Mind of Ben Burtt.” Post (Carle Place, N.Y.), vol. 23, no. 7, 2008, p.48.

Gallagher, Mike James. Star Wars: A New Hope Sound Design Explained by Ben Burtt. 2019, www.indepthsound.com/. Accessed 2020.

Harvey, Steve. “Star Wars Sound: Deep Roots, Lasting Impact.” Pro Sound News, vol. 29, no. 8, 2007, pp. 39–42.

McGee, Marshall. “The Sound Design Secrets Of The Star Wars Universe || Waveform.” YouTube, 20 Dec. 2019, youtu.be/mZSXmvAKx9Q.

“Phaser (Effect).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 21 Nov. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phaser_(effect).

Ratcliffe, Amy. “8 Things You Might Not Know About the Dianoga.” StarWars.com, 13 Aug. 2019, www.starwars.com/news/creature-feature-8-things-you-might-not-know-about-the-dianoga.

Rinzler, J.W. The Making of Star Wars. Enhanced Edition ed., Del Rey Books, 2007.

Robertson, Hal. “DIY Sci-Fi Sound Effects: Whether for Star Trek, Star Wars, or Others from the Movies and on TV, Making Sci-Fi Sound Effects Is a Fun; Creative Process That Everyone Should Try at Least Once.” Videomaker, vol. 26, no. 10, 2012, p. 58.

StarWars.com. “Air Conditioner – Conversations: Sounds In Space.” StarWars.com, www.starwars.com/video/air-conditioner-conversations-sounds-in-space.

Thomas. “Time Station CHU in The Empire Strikes Back.” The SWLing Post, 21 Dec. 2015, swling.com/blog/2015/12/thats-time-station-chu-in-the-empire-strikes-back/.

Unnamed. “Highlights from a Discussion with Ben Burtt.” The Official Star Wars Blog, 27 May 2007, starwarsblog.wordpress.com/2007/05/26/highlights-from-a-discussion-with-ben-burtt/.

Gearslutz.com, Dbbubba. Darth Vader Effect.. 6 Apr. 2007, www.gearslutz.com/board/so-much-gear-so-little-time/117836-darth-vader-effect.html.

Williams, John. “Star Wars LP Liner Notes.” JW Collection, www.jw-collection.de/scores/swlp.htm.