My Sites

Log in to create or edit your sites.

IMPORTANT SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT: Content freeze 7am June 19th until 7am June 23rd. Read more here.

Need Help? Email edtech@tufts.edu

Site-Wide Activity

-

Aleksandra Kaszowska wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Gizem Altheimer wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

In my first blog post, I talked about brain regions that showed functional differences between people with social anxiety disorder (SAD) and those without. Although this broad point of view is certainly […]

In my first blog post, I talked about brain regions that showed functional differences between people with social anxiety disorder (SAD) and those without. Although this broad point of view is certainly […] -

Jeneice Collins wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Joshua Manning wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

Taken from: http://www.photoblip.com/images/121/96ee7490878c8b7482ed7a8e8b2e2d85.jpg%5B/caption%5D

Picture yourself standing at the front of a path of red hot coals. A handful of your friends are by your side, some cheering you on while others are claiming things from your will. Would you risk burning yourself for the glory of conquering this obstacle?

Countless movies and reality TV shows have turned this scenario into the quintessential task for seeing how people react to risk. Though we all may fantasize of strutting across the coals without hesitation and completely unfazed by the apparent inferno, the way people actually evaluate and take risk into consideration before they make a decision is a complex process depending on categorical and individual factors. Using recent research and knowledge on these factors that influence risky decision making, it may now be possible to predict and maybe even consciously manipulate how you and others perceive and integrate risk.

It is well known in society and the scientific community that adolescence is directly linked with risk-taking behavior. Age is an important factor that can influence how risk is handled; there is a good chance that a group of teens would have a higher completion rate on the coal-walking challenge than a group of middle aged adults or a group of children. A study conducted by Galvan et. al. has suggested a reason for this. While performing a task depended on risk/reward manipulation, adolescents showed enhanced activity in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) than children. Interestingly, this same activity was found in adults, but adults also had significant activity in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) that adolescents and children lacked. This finding suggests that nucleus accumbens activity is functionally linked to risk-seeking behavior. The OFC, a higher-level analytical region, may need to be activated through experience and development in order to curb the risk-seeking decisions favored by analysis from the NAcc.

Another categorical factor that influences the way people assess risk during decision making is gender. Though the research can be controversial, studies have found that men show higher impulsivity and tendency for risk-taking behavior, suggesting that members of the different genders analyze risk differently. A paper published by Tatia Lee et. al. found differential brain activity during risk-taking tasks. Female participants in their study showed greater activation in the right insula and the bilateral orbitofrontal cortex than male participants. This pattern, especially the activity in the OFC, relates back to the adolescence study since it suggests that women use this higher-function brain region to analyze the effects or implications of risk to a greater extent than men.

People don’t react equally to risk even if they are in the same categories talked about above. Risk can have a significant effect on the emotional system in the brain. Differences in the sensitivities of the affective systems to risk cause differences in trait anxiety, which is the amount of unpleasant anxiety an individual feels when presented with a threat (or the possibility of a threat). According to a study by Xu et. al, trait anxiety can be seen during a risky decision task as enhanced activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, two brain regions commonly known to be a part of the emotional system. This brain activity, and the overall decision, can be manipulated by framing the risk. If it is presented as a possible negative, people are more likely to take the less risky option. If the risk is presented as a possible gain, participants were more likely to take the risk. Though this effect was seen in almost every participant, it was especially obvious in those with high trait anxiety. This means that the people more sensitive to the emotional impact of the situation can have their decision more easily manipulated by the framing of the risk. These results show how the emotional system ties into the perception of risk, and therefore its influence on the decision making process.

While there are plenty of other factors that also influence how risk can be taken into account while making a decision, recent research can allow people to vaguely predict and change how individuals are affected by risk. It might have already been easy to predict whether a male teenager or a middle aged woman would run across a stretch of coals just from categorical knowledge. Now, however, closer details emerge as factors, like how emotionally reactive the person is or was the individual listening to the positive frames (how awesome would it be to run across fire?!) or the negative frames (you’re going to burn yourself!)? And most importantly, if you find yourself on a reality TV show and need to complete this task, you now know how the decision can be made easier: act quickly so that your more conservative brain regions don’t veto the decision.

References

Adriana Galvan, Todd A. Hare, Cindy E. Parra, Jackie Penn, Henning Voss, Gary Glover, and B. J. Casey. (2006) Earlier Development of the Accumbens Relative to Orbitofrontal Cortex Might Underlie Risk-Taking Behavior in Adolescents. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(25), 6885-6892. retrieved from http://www.jneurosci.org/content/26/25/6885.full.pdf+html? sid=ad402ecb-af36-469a-9d94-4464a8432893

Shirley Fecteau, Daria Knoch, Felipe Fregni, Natasha Sultani, Paulo Boggio, and Alvaro Pascual-Leone. (2007) Diminishing Risk-Taking Behavior by Modulating Activity in the Prefrontal Cortex: A Direct Current Stimulation Study. The Journal of Neuroscience, 27(46), 12500-12505. retrieved from http://www.jneurosci.org/content/27/46/12500.full.pdf+html? sid=97259626-3f79-42ac-a12b-d3be5a901b4f

Pengfei Xu, Ruolei Gu, Lucas S. Broster, Runguo Wu, Nicholas T. Van Dam, Yang Jiang, Jin Fan and Yue-jia Luo. (2013) Neural Basis of Emotional Decision Making in Trait Anxiety. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33(47), 18641-18643. retrieved from http://www.jneurosci.org/content/33/47/18641.full.pdf+html

Tatia M. C. Lee, Chetwyn C. H. Chan, Ada W. S. Leung Peter T. Fox and Jia-Hong Gao. (2009) Sex-Related Differences in Neural Activity during Risk Taking: An fMRI Study. Cerebral Cortex, 27(11), 1303-1312. retrieved from http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/content/19/6/1303.full.pdf+htmlLila Kohrman-Glaser wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

I generally conceptualize Obsessive Compulsive disorder in terms of irrational and persistent thoughts that will go away if ignored for long enough. In this post, I challenge the way I think about OCD (sound meta?) and present up to date information on the little known metacognitive model.

According to dictionary.com, Metacognition is: Higher order thinking that enables understanding, analysis, and control of one’s cognitive processes, especially when engaged in learning. The metacognitive model of OCD was first developed by Flavell and has come to the forefront of OCD research in recent years (Rees & Anderson, 2013). Wells, a theorist about the role of metacognition in OCD, proposes that negative metacognitive beliefs arise from the appraisal of intrusive thoughts and lead to/contribute to OCD symptoms. These metacognitive thoughts specifically relate to beliefs about when to perform and stop a ritual, and thought-fusion beliefs (Rees & Anderson, 2013). A thought fusion belief occurs when an individual believes thinking about something makes it more likely to happen. For example, an OCD patient may experience significant distress after imagining that they are in a car crash because they begin to believe that they are actually going to hit someone with their car. In the rest of this post I will present some of the empirical evidence in support of the metacognitive model of OCD and discuss implications for treatment.

Solem et al. tested the two following hypothesis in their study of Wells Metacognitive model using a variety of self-reported scales assessing OCD symptoms and Metacognitions for data collection:

Metacognitions will show a significant positive correlation with obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Patients with OCD will score significantly higher on metacognitive constructs compared to community controls.They found a positive and significant correlation between metacognitions about rituals and thought-fusion beliefs, and OCD symptoms. These results provide empirical support for Wells’ model.

Another recent study demonstrated the involvement of metacognitive beliefs in development of OCD symptoms by experimentally manipulating metacognitive beliefs (Myers & Wells, 2013). Participants were placed in a fake EEG and the experimental group was told that they would hear a loud noise if they thought about drinking (induced metacognition). The control group was told that the loud noise they might hear had nothing to do with their thoughts (Myers & Wells, 2013). Results supported the hypothesis that participants in the experimental group, especially those with OCD, would experience more OCD like symptoms and discomfort than participants in the control group. For a detailed discussion of the results and limitations of the study, see the following link:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005796713000181

There are a variety of empirically tested treatments based on the metacognitive model of OCD. They all aim to improve an individual’s metacognition about the experience of unwanted and obsessive thoughts. I have provided a quick description of three empirically tested metacognitive therapies along with links to learn more and opportunities to participate in clinical trials.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The goal of ACT is to improve quality of life, not necessarily to eliminate all symptoms. Patients are taught to accept their obsessive thoughts instead of trying to suppress them and to think about their thoughts in a less literal manner.

http://contextualscience.org/act

http://www.sevencounties.org/poc/view_doc.php?type=doc&id=52497&cn=6Inference Based Therapy: Based on the premise that OCD symptoms arise from irrational and obsessional doubting. IBT intends to modify the thought processes that produce symptomatic doubting (O’Connor et al., 2009).

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1077722909000947

http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01794156Metacognitive Therapy: “The main approach used in MCT for OCD is to help the client to become aware of their metacognitive processing and to learn to modify these higher-order metacognitions such as beliefs about the importance of thoughts” (Rees & Anderson, 2013).

http://www.mct-institute.com/metacognitive-therapy

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdCUiKN6Vqg

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01483339?term=metacognitive+therapy&rank=5

I hope that this blog post has made you think about the way that you think about OCD (joke intended)! Stay tuned for my next post in 2 weeks.

References:

Myers, Samuel G., and Adrian Wells. “An Experimental Manipulation of Metacognition: A Test of the Metacognitive Model of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms.” Behaviour research and therapy 51.4-5 (2013): 177-84. ProQuest. Web. 24 Sep. 2014.

O’Connor, K., Koszegi, N., Aardema, F., van Niekerk, J., & Taillon, A. (2009). An inference based approach to treating obsessive-compulsive disorders. Cognitive and Behavioural Practice, 16, 420–429.

Rees, Clare S., and Rebecca A. Anderson. “A Review of Metacognition in Psychological Models of obsessive–compulsive Disorder.” Clinical Psychologist 17.1 (2013): 1- 8. ProQuest. Web. 24 Sep.

Solem, S., Myers, S. G., Fisher, P. L., Vogel, P. A., & Wells, A. (2010). An empirical test of the metacognitive model of obsessive-compulsive symptoms: Replication and extension. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 79–86.

http://media-cache-ec0.pinimg.com/originals/f8/ae/13/f8ae13153b8005eb5e2721c4462c8e0f.jpg

http://livelightbeing.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/9682e0cb87c5b5dfb44a9cf9e9e0c66a.jpg?w=580

Victoria A. Floerke wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

Ah, deadlines. Whether you’re finishing an assignment or paying your utilities bills, deadlines don’t exactly engender feelings of warmth and giddiness, at least in my experience. Even so, deadlines exist for a reason; I can’t just ignore my electric bill, no matter how happy it makes me in the moment, without expecting negative downstream implications. My electricity would eventually be shut off, thereby preventing me from turning my online assignment in on time, or, worse yet, from accessing my Netflix account. Clearly, then, there are times when it’s probably detrimental for me to feel positively in the immediate moment, as well as times when it’s probably beneficial for me to feel badly, at least for a little while.

[caption id="attachment_272" align="alignleft" width="300"]

So what’s the real key to happiness? You have to take the good with the bad. (Retrieved from http://media-cache-ec0.pinimg.com/736x/62/59/ed/6259ed8be7 9c6744d7f3864200418a56.jpg)

So what’s the real key to happiness? You have to take the good with the bad. (Retrieved from http://media-cache-ec0.pinimg.com/736x/62/59/ed/6259ed8be7 9c6744d7f3864200418a56.jpg)Speaking of Netflix, though, if you’re anything like me you probably find their algorithms endlessly fascinating (can you even imagine where we would be without Netflix?! But I digress). For example, I recently accidentally clicked on a link for media suggestions tailored to me based off of my viewing history instead of the link for my overstuffed self-selected queue. I was overjoyed to discover, purely by happenstance, that one of my favorite television shows of all time, Gilmore Girls, was finally available for online streaming. Perhaps my perception is tainted, but I don’t think that I watch other shows on Netflix that would predispose me to watching Gilmore Girls; but obviously Netflix knows me way better than I think it does.

Netflix’s assessment of my liking behavior, however, is neither here nor there. Why I bring this incident up is because one of Gilmore Girls’ main protagonists, Rory, has something of a quarter-life crisis that derails her future in ways that probably only a serialized television show could resolve. As a lifelong aspiring journalist, Rory writes for (and eventually serves as editor of) the Yale Daily News, and is even awarded a prestigious internship at an up-and-coming regional paper. When her boss informs her that she doesn’t have what it takes to be a journalist, though, Rory goes off the deep end, acting so rashly and selfishly that she ends up in legal trouble, takes a leave of absence from school, and cuts off all contact with her best friend (and mother), Lorelai.

While the insights one can take from a television drama geared towards a predominately teenage female demographic should probably be taken with a grain of salt, there are nevertheless many aspects of Rory’s meltdown that map onto recent scientific evidence concerning why context matters when we’re deciding how we want to feel. We’ll get to those ideas more in our next section.

When Can Wanting to Feel Good be Bad?

Since positive emotions tend to make us feel really great, it’s probably counterintuitive to consider that they might sometimes not be so good for us. Yet emotion science has paradoxically demonstrated that if I really want to feel happy I’m going to actually feel less happy than if I don’t really want to be happy. Why is that? An easier way to consider this problem is to think about emotions as goals. Let’s say my goal in a given moment is to feel happy. If I highly value feeling happy but try to become happy by, say, not paying my water bill, I’m inevitably going to fail. My failure to become happy will lead me to feel disappointed, which will undermine the very happiness I was trying to achieve in the first place (Schooler, Ariely, & Lowenstein, 2003; Mauss et al., 2011).

Of course, wanting to feel happy isn’t always bad. Indeed, it may simply be the case that valuing certain types of happiness is bad. In my last post, I talked about all of the different ways that I tend to define happiness. While there are innumerous things I could list that make me happy, the happiness that all people seek tends to fall under one of two categories: hedonic happiness, which is happiness derived through “feeling good” and experiencing pleasure, and eudaimonic happiness, which is happiness derived through meaning-making. It’s been found that these two types of happiness have very different effects. In one study, people whose ventral striatum was activated during eudaimonic (or prosocial) decision-making were more likely to experience a long-term reduction in depressive symptoms, whereas people whose ventral striatum was activated during hedonic (or selfish or risky) decision-making were more likely to experience a long-term increase in depressive symptoms (Telzer et al., 2014). These findings suggest that perhaps the seemingly perplexing finding that people who highly value happiness are less happy than people who don’t highly value happiness may be at least partially explained by differences in how people try to achieve happiness. They also explain why Rory, who made a lot of impulsive decisions while simultaneously shutting out the most meaningful person in her life, might not have achieved the positive emotional experience she thought she would.

Regardless of how people define happiness, though, positive emotions can still be problematic. Independent of how happy people are, too much positive emotion variability across one day (or even two weeks) is associated with things like poor well-being, less satisfaction with life, increased anxiety, and even greater depressive symptomology (Gruber et al., 2013). This means that experiencing too much or too little positive emotion in a relatively short timeframe can be maladaptive. Thus, as with most things in life, positive emotions should be sought out (and experienced) in moderation.

When Can Wanting to Feel Bad be Good?

Even if you bought my previous claim that positive emotions can sometimes be detrimental to us, you might still lose me now, because I’m going to suggest that negative emotions can sometimes help us. I know, I know, how can something so bad be good? Well, as was the case with positive emotions, it’s probably useful to think about this question while considering that emotions can be goals. We tend to seek out negative emotions when they’re useful for us (Tamir & Ford, 2009). We also know that anger, a highly arousing negative emotion, is associated with aggression, and that this link can be increased when the left frontal cortex is manipulated by a technique called transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS; Hortensius, Schutter, & Harmon-Jones, 2012). Anger is a very negatively connoted word, but it isn’t always destructive; on the contrary, anger can sometimes be beneficial, even when one is angry about something as divisive as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, so long as one doesn’t have a strong hatred for the person or group they’re dealing with (Halperin et al., 2011).

Keeping all of these aforementioned findings about how negative emotions like anger can sometimes be good in mind, let’s revisit Rory’s breakdown. Had she been angry instead of, well, heartbroken by her boss’ critique of her, she might’ve become aggressive enough to be highly motivated to prove him wrong. Up-regulating this anger probably would’ve kept her from leaving school and otherwise derailing her life. If she came to hate her boss and became too angry or aggressive, though, she might still have run into trouble with the law; so, again, it’s probably best to seek out and experience negative emotions in moderation.

Where Do We Go From Here?

We still have a lot to learn about how wanting to feel good can be bad and how wanting to feel bad can be good, especially in terms of understanding the neural mechanisms that underlie how and when we decide to up-regulate or down-regulate positive and negative emotions. Even so, there seems to be a growing consensus that emotions, be they positive or negative, all have adaptive value in different contexts. Rory Gilmore learned the hard way that she has to take the bad with the good, and eventually she rallies to get her life back on track. This positive-negative emotion balance she achieves is critically implicated in the treatment of various psychopathologies, like depression and bipolar disorder, which we’ll discuss more next time. Until then, I’m going to seek out hedonic happiness by re-watching a lot more episodes of Gilmore Girls. Don’t worry about my eudaimonic happiness, though; I’ll be sure to laugh through them all in the company of good friends.

References

Gruber, J., Kogan, A., Quiodbach, J. & Mauss, I. B. (2013). Happiness is best kept stable: Positive emotion variability associated with poorer psychological health. Emotion, 13(1), 1-6.

Halperin, E., Russell, A., Dweck, C., & Gross, J.J. (2011). Anger, hatred, and the quest for peace: Anger can be constructive in the absence of hatred. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(2), 274-291.

Hortensius, R., Schutter, D. J., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2012). When anger leads to aggression: Induction of relative left frontal cortical activity with transcranial direct current stimulation increases the anger–aggression relationship. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(3), 342-347.

Mauss, I. B., Tamir, M., Anderson, C. L., & Savino, N. S. (2011). Can seeking happiness make people unhappy? Paradoxical effects of valuing happiness. Emotion, 11(4), 807.

Schooler, J. W., Ariely, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2003). The pursuit and assessment of happiness can be self-defeating. In J.C.I. Brocas (Ed.), The Psychology of Economic Decisions (Vol. Rationality and Well-Being, pp. 41–70). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sherman-Palladino, A. (Executive Producer). (2000). Gilmore girls [Television series]. Burbank: The WB Television Network.

Tamir, M., & Ford, B. Q. (2009). Choosing to be afraid: Preferences for fear as a function of goal pursuit. Emotion, 9(4), 488.

Telzer, E. H., Fuligni, A. J., Lieberman, M. D., & Galván, A. (2014). Neural sensitivity to eudaimonic and hedonic rewards differentially predict adolescent depressive symptoms over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(18), 6600-6605.

-

Maureen Hilton wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Jeffrey Aalberg wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

Neurosurgery is by no means a modern invention. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is instead a result of millennia of humans trying to impact behavior and health by physically altering the brain. The first post in this blog gave an overview of what DBS is and why it is used. This post will briefly cover the history of neurosurgery; looking at the advances that lead to DBS as a viable therapeutic method.

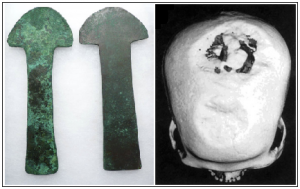

Trepanning: Trepanning was a widespread phenomenon. The left image shows tools used in the procedure from South America in the first millennium. The right image show a Neolithic skull from 5100 with evidence of the procedure (Robinson et al., 2012)

The earliest example of neurosurgery that we have evidence of is trepanning. This was the practice of drilling a hole in the skull in order to relieve a patient of some malady. Some postulate it was thought that demons causing psychological symptoms needed to be released. The earliest example is a Neolithic burial in Alsace France, dating to 5100BC. The holes in the skull have evidence of healing, suggesting that it was done intentionally, and not a result of an accident (Robinson et al., 2012). Even the idea of stimulating the brain as a medical treatment is not novel. Scribonius Largo, a roman physician in 46 AD applied electric eels to patient’s foreheads and reportedly demonstrated amelioration of headaches(Sironi, 2011).

Frontal Lobotomy. Axial and sagittal views of a lobotomy. Notice the diffuse damage in the images, most notably the bright white swath across both hemispheres on the left. (Lapidus, 2013).

Functional neurosurgery had a resurgence around the First World War. Mental asylums were packed, a situation made worse war veterans returning home and a lage number advanced syphilis cases before penicillin was discovered. This environment influenced the development and popularization of the frontal lobotomy by Egas Moniz and Walter Freeman. The transcranial frontal lobotomy had severe consequences for patients. They often showed a reduction of their initial psychological symptoms, but at the cost of extreme apathy and personality defects. The demure state of these patients meant less work for mental institutions, but the procedure soon became obsolete under a critical public eye (Robinson et al., 2012).

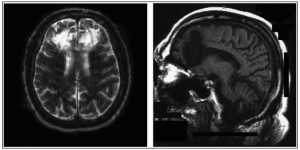

A stereotaxic device: An early example of a stereotaxic device from 1908. The first human stereotaxic experiments were not done until 1947(Robinson et al., 2012).

The next frontier in neurosurgery was ablative therapy. This was the lesioning, often by radioactive rods, of areas in the brain. Initially a crude procedure, it was refined with the the advent stereotaxic technique in 1947. Stereotaxic technique is the practice of holding the head in a fixed position, and then using reference points on the brain, skull, imaging techniques and prior knowledge of brain mapping to precisely access areas of the brain. This technique saw the rise of lesions as an effective treatment for many disorders (Sironi, 2011)

Stimulation of the periventricular/periaqueductal grey matter as well as some areas of the thalamus was demonstrated to be extremely effective at controlling pain that was difficult to treat pharmaceutically (Kumar et al., 1990). In large part due to these treatments, it was shown that high frequency electric currents had a similar effect as ablative therapies. At the time, surgeons were treating tremor disorders and Parkinson’s disease by thalamotomy, or destruction of areas of the thalamus. While this treatment improved symptoms, it often caused dysarthria, an issue with the motor control of speaking. The stimulation of DBS was shown to be as, if not more, effective that ablation, with fewer side effects, and less surgeries needed (Tasker 1998). Further evolution of the technique looked at specific nuculi of the thalamus as well as the palladium (Limousin-Dowsey et al., 1999).

This prior body of scientific work lead to excitement about the use of DBS and the exploration of how it could be used in treating other neurological and psychiatric disorders. Obsessive disorders were among the first affective disorders to be treated in the early 21st century. The role of DBS in depression therapies has only very recently been studied (Lapidus et al, 2013). The background of neurosurgery is necessary to establish the context in which current research of depression is operating. We will examine the current theories and specifics of deep brain stimulation for depression in our next post.

References:

Kumar, K., Wyant, G., & Nath, R. Deep brain stimulation for control on intractable pain in humans, present and future: A ten-year follow-up. (1990). Neurosurgery, 26(5), 774-782. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

Lapidus, K., Kopell, B., Ben-Haim, S., Rezai, A., & Goodman, W. (2013). History of Psychosurgery: A Psychiatrist’s Perspective. World Neurosurgery, 80, S27.e1-S27.e16. Retrieved September 26, 2014, from PubMed.

Limousin-Dowsey, P., Pollak, P., Van Blercom, N., Krack, P., Benazzouz, A., & Benabid, A.(1999). Thalamic, subthalamic nucleus and internal pallidum stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology, (246), 42-45. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

Robison, R., Taghva, A., Liu, C., & Apuzzo, M. (2012). Surgery of the Mind, Mood, and Conscious State: An Idea in Evolution. World Neurosurgery, 77, 662-686. Retrieved September 26, 2014, from PubMed

Tasker, R. (1998). Deep Barin Stimulation is Preferable to Thalomotomy for Tremor Suppression. Functional Neurosurgery, (49), 145-154. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

-

Amy M. Smith wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Lindsay A. Hinzman wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

In this post I will focus on the interplay of an eye gaze and emotion as they relate to perceiver-target interactions. Eye gaze plays an important factor in social interactions. It cues us to know when someone is talking to us. It can also convey information about the environment. Imagine that you see a mouse run across the room. You yell in fear and look in that direction.

The direction of your eye gaze tells everyone else in a room that there is a potential threat, and where to watch out for it. In this way, emotion and eye gaze complement each other to convey your specific message in a social environment. I’ll explore this interplay from various angles. First, I’ll describe some research about how the gaze conveyed by a target influences a perceiver’s perception of target’s emotion. Next I’ll describe some evidence purporting that a target’s eye gaze can influence the emotional experience of a perceiver. And finally, I’ll discuss how a perceiver’s emotional disposition can influence their gaze towards emotional faces. Overall, I’ll attempt to convey to you that this interaction between eye-gaze and emotion plays an important role in all aspects of social interactions.

The direction of your eye gaze tells everyone else in a room that there is a potential threat, and where to watch out for it. In this way, emotion and eye gaze complement each other to convey your specific message in a social environment. I’ll explore this interplay from various angles. First, I’ll describe some research about how the gaze conveyed by a target influences a perceiver’s perception of target’s emotion. Next I’ll describe some evidence purporting that a target’s eye gaze can influence the emotional experience of a perceiver. And finally, I’ll discuss how a perceiver’s emotional disposition can influence their gaze towards emotional faces. Overall, I’ll attempt to convey to you that this interaction between eye-gaze and emotion plays an important role in all aspects of social interactions.

A target’s facial emotion and eye gaze influence a perceiver

Adams and Kleck (2005) examined how eye gaze influences perception of emotional faces. They first examined whether eye gaze direction would influence which emotions people attribute to neutral faces. Participants were presented with emotionally neutral faces,half depicting direct eye gaze and the other half depicting averted eye gaze. After looking at each face, participants rated the likelihood that the person in the picture would experience the emotions anger, fear, sadness, and joy, on a scale from 1 to 7. The results demonstrated that when looking at a picture of a neutral face displaying direct eye gaze, participants were more likely to attribute approach-related emotions of joy and anger. Conversely, averted target gaze facilitated participants’ attributions of avoidance-related emotions, sadness and fear.

Example of emotionally ambiguous stimuli used in Adams and Kleck (2005) blending fear and anger, depicting direct gaze (left) and averted gaze (right).

Next, they examined how direct versus averted eye gaze would influence participants’ emotional attributions in response to emotionally ambiguous faces. Following a similar procedure, participants made emotional attributions of 4 emotions (anger, fear, sadness, joy) using a 7-point scale. This time, instead of looking at neutral faces, participants were presented with face stimuli that blended two emotions: anger and fear. Consistent with the previous study, they found that direct eye gaze facilitated perceptions of anger in the ambiguous face while averted gaze facilitated perceptions of fear.

In a final study, they measured the extent to which gaze direction influenced perceptions of emotional intensity among highly prototypical emotional faces. Participants viewed faces depicting prototypical representations of anger, fear, happiness, and sadness, depicting either direct or averted gaze and rated the emotional intensity of the target’s emotion. They found that direct gaze increased participants’ intensity ratings when it was depicted on an angry or happy face, and that averted gaze increased participants’ intensity ratings when it was depicted on a fearful or sad face. Therefore, across three studies, they demonstrate a link between gaze direction and emotion: direct gaze facilitates perception of approach-related emotions such as anger and happiness while averted gaze facilitates perception of avoidance-related emotions, such as fear and sadness.

Target’s gaze influences a perceiver’s emotion

Other work has examined the extent to which direct versus averted eye gaze elicits biological responses associated with viewing approach versus avoidance behaviors. Previous work has demonstrated that stronger EEG activation in the left and right frontal cortices is associated with approach- and avoidance-related behaviors, respectively (Van Hon & Schutter, 2006). Furthermore, skin conductance (SCR) has been associated with arousal (Andreassi, 2000). Based on this previous work Hietanen, Leppänen, Peltola, Linna-Aho, and Ruuhiala (2008) set out to explore the effect of direct versus averted eye gaze on participants’ physiological reactions to faces. Recognizing a dearth of research employing real-life faces (and a n abundance of research using photographs of faces), the authors also compared participants’ responses to real-life faces versus photographs of faces.The participants viewed either a real-life face or a photograph of a face depicting a neutral expression and either direct or averted eye gaze. Researchers collected participant’s skin conductance and EEG data, and asked participants to report subjective ratings of arousal. Consistent with the original hypotheses, the results demonstrate greater right-side EEG activation when participants viewed the face demonstrating direct eye gaze. Conversely, greater left-side EEG activation was observed participants viewed the face demonstrating averted eye gaze. Furthermore, SCR results demonstrate that participants experience greater arousal when viewing faces depicting direct gaze. Importantly, all patterns of significant results were elicited only from the conditions in which participants viewed live faces, suggesting that photographic face stimuli may not be sufficient from eliciting certain approach- and avoidance-related responses.

Perceiver’s emotional state influences target perception

Next, I’ll explore some evidence that a perceiver’s emotional disposition can influence their gaze orientation towards a target (Mogg, Garner & Bradley, 2007). Mogg and colleagues recruited two groups of participants: high-anxiety and low-anxiety individuals to participate in an eye-tracking experiment. Participants’ eye movements were recorded as they looked at an array of stimuli that conveyed fear or anger along a continuum.They found that both groups of participants preferentially directed their eye gaze towards threat-related emotions of anger and fear (compared to neutral emotional faces). They also found that compared to low-anxiety participants, high-anxiety participants demonstrated stronger gaze orientation towards the threat-related stimuli when the faces depicted highly prototypical angry or fearful expressions. The differences they observed among high- and low-anxiety participants are consistent with theories of anxiety that posit anxious individuals are more sensitive to threat-related cues (Mogg and Bradley, 1998). One way in which this heightened sensitivity can manifest is through greater attention towards threat cues (Mogg and Bradley, 1998).

So to wrap this up, we’ve explored ideas related to ways that emotion and gaze interact to influence all aspects of interpersonal perception. One thing you may notice is that much of the current work focuses on anger and fear, while ignoring many other emotions. It will be interesting to see how the literature develops as we begin to explore other emotional domains.

References

Adams, R. B., & Kleck, R. E. (2005). Effects of direct and averted gaze on the perception of facially communicated emotion. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 5(1), 3–11. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.3

Andreassi, J. L. (2000). Psychophysiology: Human behavior & physiological response (4th ed.). NewJersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate.

Hietanen, J. K., Leppänen, J. M., Peltola, M. J., Linna-Aho, K., & Ruuhiala, H. J. (2008). Seeing direct and averted gaze activates the approach-avoidance motivational brain systems. Neuropsychologia, 46(9), 2423–30. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.029

Mogg, K., Garner, M., & Bradley, B. P. (2007). Anxiety and orienting of gaze to angry and fearful faces. Biological Psychology, 76(3), 163–9. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.07.005

Mogg, K., Bradley, B.P., 1998. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy 36, 809–848. -

Rebecca Rago wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 8 months ago

Welcome back to my blog series about emotion and our senses! Last post, we learned about our senses in general interact with our emotions. This post will specifically focus on how our visual system helps us navigate the world of emotion. It will also explore how the emotions of those with non-functioning visual systems are impacted.

Think of a mystery movie. The characters just entered somewhere to investigate. What is the first thing that one character says to another? They say “what do you see?” Our eyes help us in our acquisition of information (including emotional information). We understand emotions through visual cues. If you saw someone in tears, what would you say? You would ask them why they were sad. This is due to the aid of our vision in identifying and processing emotion.

What emotion is she displaying? The tears are a visual cue that tell us she is sad.

How we define something as emotional starts with our vision. Schupp et. al (2003) believed that visual cues were responsible for emotional categorization. Participants sawpictures and categorized them as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. Their reactions were measured using ERPs. There were stronger, more negative ERP responses in visual areas of the brain. This shows that we quickly identify something as emotional from visual cues. From an evolutionary standpoint this makes sense. You identify someone as sad by tears rather than by a distinct smell. One step further than just categorization, our visual cortex helps us process emotion.

Lang et. al (1998) studied our visual cortex in relation to emotional processing. The Participants were in an fMRI scanner and saw emotional or neutral pictures. Lang found that for emotional pictures there was more activation of the visual cortices. They concluded that emotional processing begins with vision. I agree with this, but I would be curious to see another follow up study. What would happen if the same image was presented more than once? Would the activation lower? It may be possible that the visual activation happens only as a note to the brain to continue to process something. Once something has been fully processed perhaps the visual signals are less important. I have mentioned how vision helps in categorizing and processing emotion, but what about people who have non-functioning visual systems? Can they still emote “normally”?

The athlete on the left is blind. Can you tell that just from her expression? Probably not!

We learn a lot about the world from interacting with others. Galati et. al (2001) believe, however, that our spontaneous emotional expression does not need to be visually learned. They tested this by showing participants videos of blind or sighted children making expressions. They triggered these emotions in various ways such as taking a snack away(anger) or being with a caregiver (happiness). Surprisingly, accurate participant judgment was not significantly different between the two groups. Galati et. al (2001) argue that the physical expression of emotion is independent of our visual learning. They believe spontaneous expressions are thus innate and not visually learned. A similar conclusion was drawn by Matsumoto and Willingham (2009). When they compared and coded photographs of blind and seeing athletes, they found emotional expression to be statistically the same. This emphasizes that emotional expression is independent of visual learning.

Our visual system has a complex relationship with emotion. In some aspects it is very involved: our visual cortex is activated to help us process and identify emotions. In other ways, it is less involved: visual learning of emotion may be minimal. This could mean that expressing emotion (despite it being something that is inherently seen) functions through a different system. This makes sense, since blind individuals still need to express emotions in order to adapt and operate in social situations. Next week, we will see how our sense of hearing affects our emotions. Stay tuned!

References:

[Crying Woman Photograph] Retrieved October 24, 2014, from: http://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/02/cry.aspx[Blind and Seeing Athlete Photographs] Retrieved October 24, 2014, from: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/psysociety/2014/02/17/olympics1/

Galati, D., Miceli, R., & Sini, B. (2001). Judging and coding facial expression of emotions in congenitally blind children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25(3), 268-278.

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., Fitzsimmons, J. R., Cuthbert, B. N., Scott, J. D., Moulder, B., & Nangia, V. (1998). Emotional arousal and activation of the visual cortex: an fMRI analysis. Psychophysiology, 35(2), 199-210.

Matsumoto, D., & Willingham, B. (2009). Spontaneous facial expressions of emotion of congenitally and noncongenitally blind individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(1), 1.

Schupp, H. T., Markus, J., Weike, A. I., & Hamm, A. O. (2003). Emotional facilitation of sensory processing in the visual cortex. Psychological science, 14(1), 7-13.

-

Geraldine Grimm posted an update 10 years, 8 months ago

Also los, ihr Penner! Fleißig bloggen!

-

Geraldine Grimm changed their profile picture 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Katherine Morley wrote a new post on the site What's New @ HHSL 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Gregory D. Frost is attending Seminar II. 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Gregory D. Frost is attending Seminar II. 10 years, 8 months ago

-

dhan02 is attending Seminar III. 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Sara M. Demers is attending Seminar III. 10 years, 8 months ago

-

jsafer01 is attending D'16. 10 years, 8 months ago

-

Rebecca Philio wrote a new post on the site What's New @ HHSL 10 years, 8 months ago

- Load More