Atrocities, 1971 – 1979

Violence under Idi Amin occurred in three primary phases. The first phase targeted the armed forces and police, occurring as a series of barrack massacres. Initially, the targets were soldiers from the Acholi, Langi, and other tribes who were assumed to be loyal to Obote. At the beginning of Amin’s reign, from January to May 1971, several hundred of these officers were killed. However, mass purges of Acholi and Langi within the military and police forces spiked from May to July of 1971. It is estimated that 5,000–6,000 Ugandans from these forces lost their lives, including in barrack massacres in Mbarara (~150–250 killed), Moroto (~120 killed), Jinja (~800 killed or disappeared), and Magamaga Ordnance Depot (~50 killed).[i]

Over his reign, Amin’s army grew from 10,000 soldiers to 25,000. It was made up of mostly foreigners, further exasperating ethnic tensions.[ii] In addition to foreigners, Amin’s army was also comprised of a large number of Muslims, who compose a very small percentage of Uganda’s population.[iii] Purges of the armed forces decreased as Amin’s army became more international in its composition.[iv] However, barrack massacres occurred in 1972, 1973, and 1977.[v]

The second phase of mass killings was the less organized and more arbitrary targeting of civilians by the military. Specific dates and numbers for this phase are difficult to determine. Soldiers not only followed Amin’s orders to kill, but a 1971 decree gave the military the power to detain anyone who they thought was culpable for sedition.[vi]

Therefore, soldiers often used their own discretion to kill those who were deemed to be a part of the opposition or abused their authority to target people as a means to settle the personal vendettas. Though tribes assumed to be disloyal to Amin, like the Acholi and Langi, were the first targets of Amin’s wrath, nearly every ethnic group had been a target of killings by the time he lost power.[vii]

The third and final phase of killings occurred towards the end of Amin’s reign. There were additional ethnic purges of military forces and a spike in civilian casualties as the rebel movements against Amin’s regime increased in strength. In 1978 Tanzanian soldiers discovered the bodies of 120 dead Ugandan soldiers close to Tanzania’s border with Uganda. It is not known for certain how the soldiers were killed or why their bodies were found in Tanzania, but the Government of Tanzania released a statement saying that the soldiers had been “dumped” in Tanzania after being executed in Uganda.[viii]

Backed by the Tanzanian army, the Ugandan National Liberation Front overthrew Idi Amin in a coup on April 11, 1979. A year before, Amin had chased political dissidents into Tanzania and subsequently invaded the Kagera Region along the western shores of Lake Victoria in Tanzania. Tanzania’s involvement in the coup began as a campaign to reclaim this territory, but it ended with Tanzanian forces fighting with the Uganda National Liberation Front all the way to Kampala to overthrow Amin.[ix]

However, instances of mass violence did not immediately stop. For example, after Tanzanian troops entered the northern Ugandan town of Gulu, young Acholi warriors massacred over one hundred people who were members of tribes from Amin’s homeland, the West Nile region.[x]

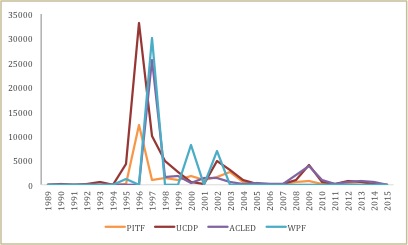

Fatalities

The International Commission of Jurists provided the most accurate and

widely cited[xi] estimation of the total number of deaths that occurred under Amin’s rule. In their 1977 report, Uganda and Human Rights, they state that:

It is still not possible to make any reliable estimate of the number who

have died. Two former ministers, Mr. Kibedi and Mr. Rugumayo, agree that the death total in the first two years of President Amin’s regime was at least 80,000 to 90,000. Many sources believe that the figure is now well over 100,000.[xii]

On June 15, 1978, Amnesty International presented a report to the Foreign Relations sub-committee of the U.S. Senate that stated 300,000 people had died under the rule of Idi Amin.[xiii] A 1999 Human Rights Watch publication, Hostile to Democracy: The Movement Systems and Political Repression in Uganda, cites an estimate given by the New York City Bar Association’s Committee on International Human rights that puts the number of deaths between 100,000 and 500,000.[xiv] A USAID report estimates that at least 10,000 Ugandans died during Amin’s first year in power.[xv]

Endings

Purges and assaults against civilians continued throughout Idi Amin’s time in power, declining only when the Ugandan National Liberation Front and the Tanzanian army overthrew Idi Amin in a coup on April 11, 1979. However, even with the ousting of Amin, instances of mass violence perpetrated by multiple actors continued in the time immediately after his demise. Further, his overthrow marked a change in the patterns of violence against civilians, not an end.

Coding

This case is coded as ending by international military defeat. Following the overthrow of Idi Amin, is another period of atrocities under the second Milton Obote regime, treated as a separate case.

____________________________

Works Cited

Amnesty International. 1979. Amnesty International Report, 1979. London: Amnesty International Publications.

Amnesty International. 1985. Amnesty International Report, 1985. London: Amnesty International Publications.

Avirgan, Tony, and Martha Honey. 1982. War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Westport, CT: L. Hill.

Decalo, Samuel. 1989. Psychoses of Power: African Personal Dictatorships. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Human Rights Watch. 1999. Hostile to Democracy: The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Ingham, Keneth. 1994. “Obote : a political biography,” London; New York: Routledge.

International Commission of Jurists. 1977. Uganda and Human Rights: Reports to the UN Commission on Human Rights. Geneva: Commission.

Kasozi, Abdu. 1994. The Social Origins of Violence in Uganda, 1964-1985,

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Keatley, Patrick. 2003. “Idi Amin.” The Guardian, accessed November 14, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/news/2003/aug/18/guardianobituaries.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1984. Imperialism and Fascism in Uganda. Trenton, NJ: Africa World of the Africa Research & Publications Project,

Mazurana, Dyan and Anastasia Marshak, Jimmy Hilton Opio, Rachel Gordon and Teddy Atim. 2014. “The Impact of serious crimes during the war on households today in Northern Uganda.” Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium, Briefing Paper 5, May. Available at: http://www.securelivelihoods.org/publications_details.aspx?resourceid=298

Accessed January 12, 2017.

Mutengesa, Sabiiti. 2006. “From Pearl to Pariah: The Origin, Unfolding and Termination of State-Inspired Genocidal Persecution in Uganda, 1980-85.” How Genocides End, accessed December 6, 2013, http://howgenocidesend.ssrc.org/Mutengesa/

Ofcansky, Thomas P. 1996. Uganda: Tarnished Pearl of Africa. Boulder, CO: Westview.

United States Library of Congress. 1992. “Library of Congress Country Studies: Uganda,” Washington, D.C. : Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Accessed 1 Dec. 2013, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/ugtoc.html.

Waugh, Colin. 2004. Paul Kagame and Rwanda: Power, Genocide and the Rwandan Patriotic Front. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co.

[i] Avirgan and Honey 1982, 31.

[ii] Avirgan and Honey 1982, 7.

[iii] Avirgan and Honey 1982, 8.

[iv] Mamdani 1984, 42.

[v] Avirgan and Honey 1982, 7.

[vi] Decalo 1989, 100.

[vii] Decalo 1989, 102.

[viii] Avirgan and Honey 1982, 69.

[ix] United States Library of Congress 1992.

[x] Avirgan and Honey 1982, 179.

[xi] Keatley 2003.

[xii] International Commission of Jurists 1977, 167.

[xiii] Amnesty International 1979, 38.

[xiv] Human Rights Watch 1999, 32.

[xv] Human Rights Watch 1999, 32.