By Becky Cogbill, 4th Grade Teacher in Medford Public Schools

I started my journey with Novel Engineering through the course offered by Tufts. I was a relative newcomer to teaching engineering and eager to learn how to do so effectively. Novel Engineering represented a large shift from my original approach. I had to let go of a lot of my structure and idea about what I should get as an end result. Instead, we focused on the process and thinking critically about decisions throughout. This student-driven learning was sometimes surprisingly successful, even for typically struggling students. At other times, though, it was really hard to step back and let the students find out, on their own, that their idea wouldn’t work. Although I don’t usually tell kids that their idea wrong, I do tend to try to ask questions that suggest they need to rethink their ideas. Changing my role in the process was hard, but ultimately seemed to benefit the students!

I started my journey with Novel Engineering through the course offered by Tufts. I was a relative newcomer to teaching engineering and eager to learn how to do so effectively. Novel Engineering represented a large shift from my original approach. I had to let go of a lot of my structure and idea about what I should get as an end result. Instead, we focused on the process and thinking critically about decisions throughout. This student-driven learning was sometimes surprisingly successful, even for typically struggling students. At other times, though, it was really hard to step back and let the students find out, on their own, that their idea wouldn’t work. Although I don’t usually tell kids that their idea wrong, I do tend to try to ask questions that suggest they need to rethink their ideas. Changing my role in the process was hard, but ultimately seemed to benefit the students!

Like with any new method of teaching, there was a learning curve for the students, too. At the beginning, many of my students rushed through the process. The idea of building something was exciting, but planning out their building, not so much! Some of them also let their imaginations take them too far out of practical, testable ideas. There were the usual disagreements and dominant personalities that required mediating. I learned that larger groups, even groups of 3 or 4, frequently meant not all students participated as much. In contrast, groups of two meant that no one could hide and many of my quieter or lower students stepped up to the plate. I was pleased that one of the skills that is generally hardest for my 4th graders, revising, was much more intuitive for them in this process. There was, usually, a concrete way to tell if their idea worked. If it didn’t, they naturally wanted to fix it so that it would work. As I realized the pitfalls for the students, I also realized how I could model, ask questions, and facilitate interactions that avoided those pitfalls.

By the end, I realized how integrated engineering could be with the rest of my curricula. Instead of doing isolated, one-lesson projects to meet the engineering standards on the report card, I now know how to create meaningful engineering units that deepen students’ thinking and skills in other areas, as well. Being able to work together, thinking about problems and solutions, and analyzing characters were all wrapped up within our engineering challenges. The commitment of class time and energy felt well worth it.

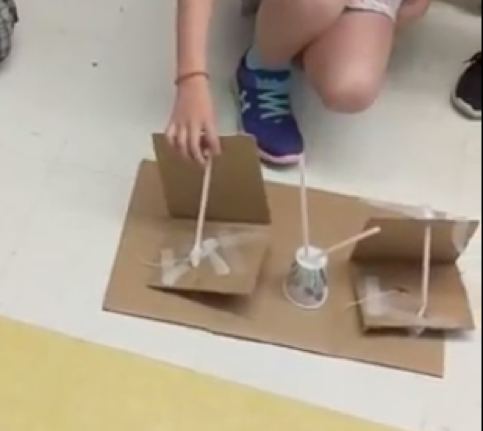

One group’s engineering project for The Earth Dragon Awakes by Laurence Yep. This student is demonstrating a safer building structure for earthquakes. She is showing that when trying to tip the building on the left, it would remain mostly upright instead of falling over.