By Walker Wind, Undergraduate in Mechanical Engineering

Tufts Center for Engineering Education and Outreach (CEEO) has a research project exploring a chemical reaction that occurs on some musical instruments called acid bleed. Walker Wind, CEEO Summer Intern and Student Teacher Outreach Mentorship Program (STOMP) Fellow, has been working for CEEO this past summer on this project and recently went to the Vincent Bach instruments manufacturing facility in Elkhart, Indiana, for one week to learn about the manufacturing process in order to determine what causes the acid bleed. Read below to learn all about Walker Wind’s trip this summer.

At this facility that I visited, they focus on making brass instruments, particularly trumpets and trombones. Over the course of my week-long visit, I had the opportunity to witness their complex manufacturing process and work with engineers at their facility on their problem surrounding acid bleed.

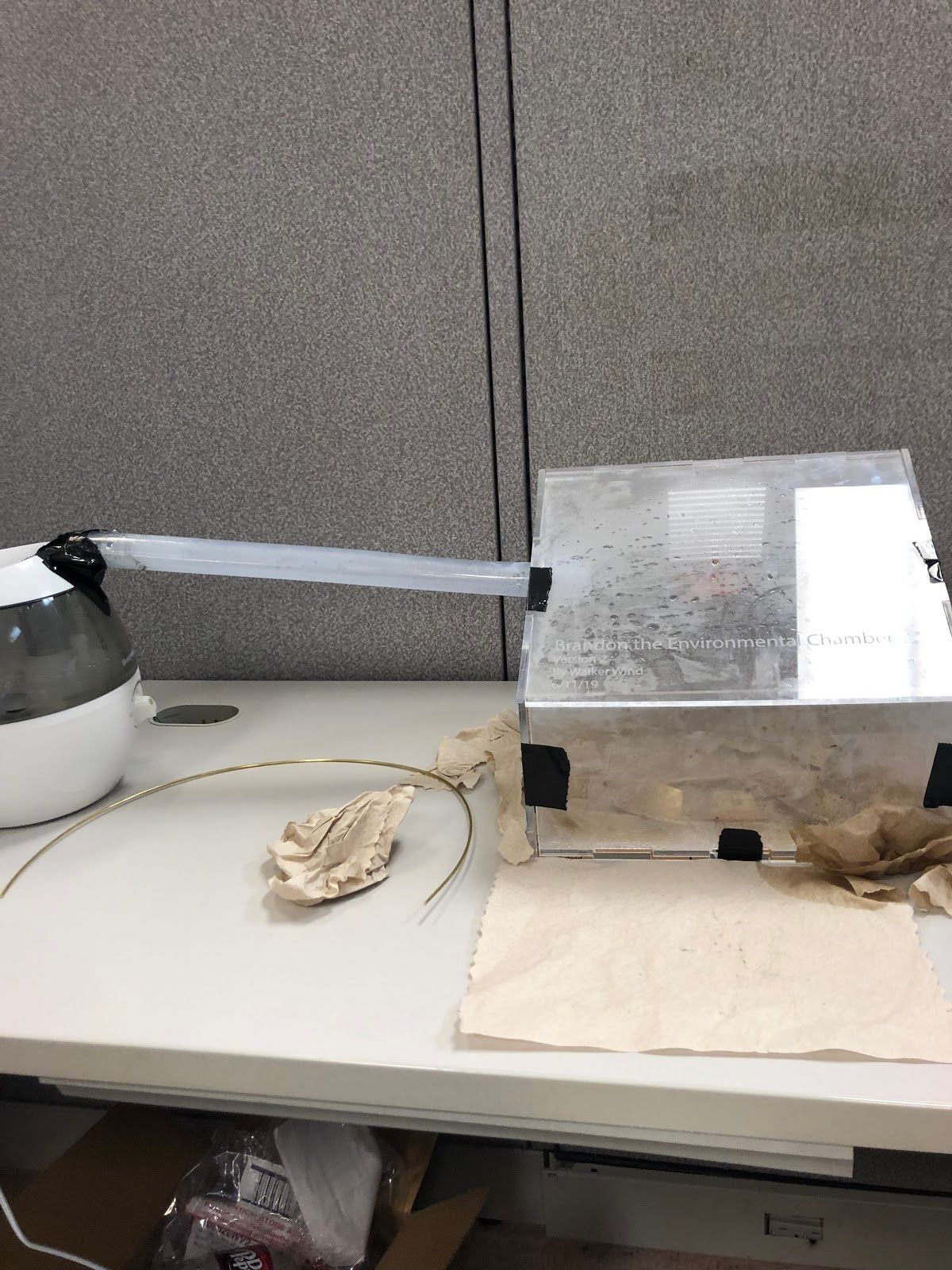

As part of the CEEO Summer Internship program, I was hired to work in Professor Chris Rogers’ lab for ten weeks. I was assigned to work on the acid bleed project, with advising from Mechanical Engineering Professors Chris Rogers and Anil Saigal. The research project was with Conn-Selmer, one of the US leaders in manufacturing all types of musical instruments. My goal was to understand and eliminate a chemical reaction called acid bleed that occurs on some of their musical instruments. In the first three weeks of the project, I worked on replicating the reaction in order to understand what might be causing it and get acquainted with practices in working with brass. I also worked on constructing a humidity chamber using a vaporizer, tubing, and acrylic. To go along with the humidity chamber, I worked on making a system of sensors and website to check the humidity and time in the chamber.

What is Acid Bleed?

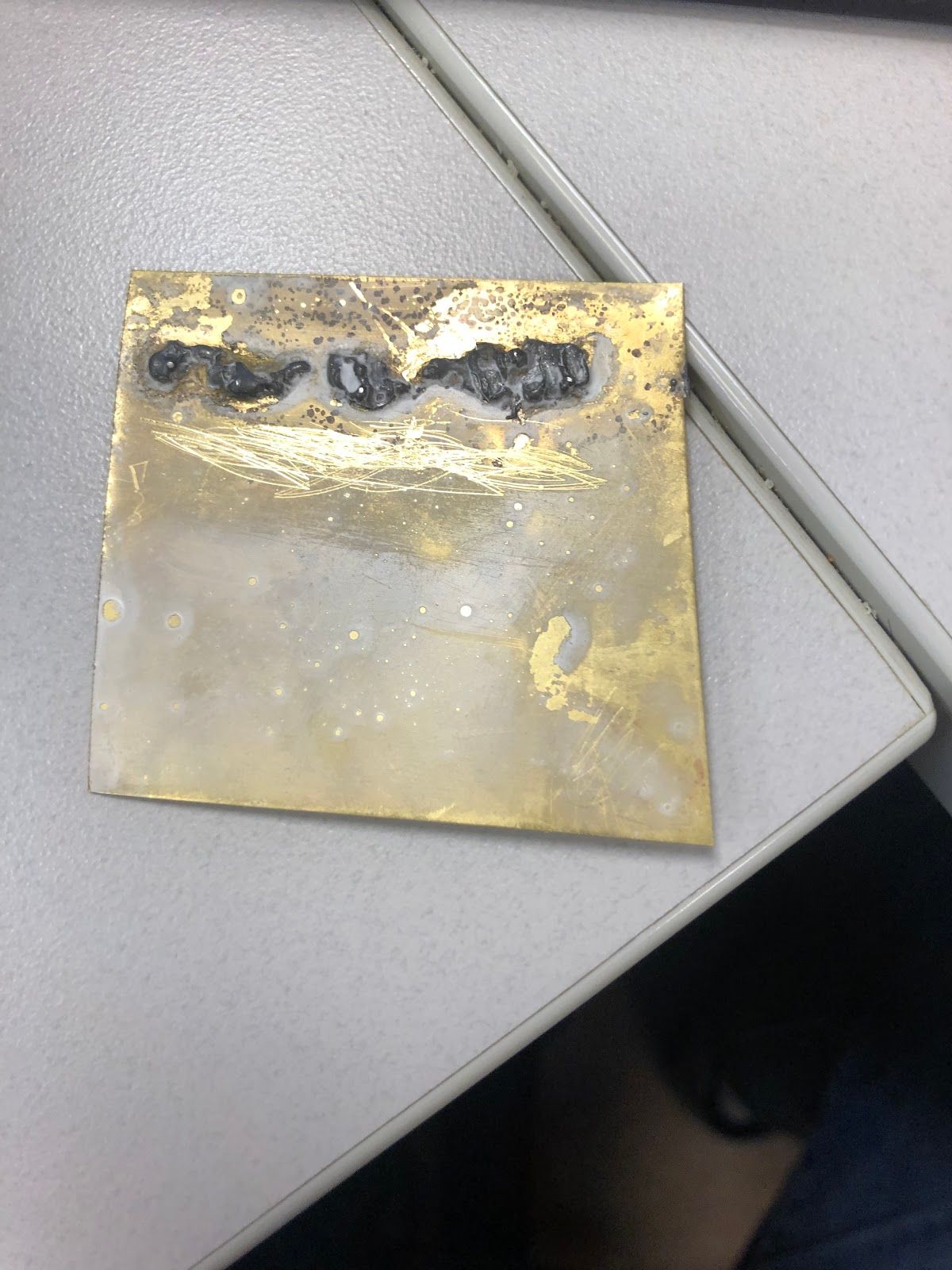

Acid bleed is the term used by engineers at Conn-Selmer to describe a defect that occurs on a small percentage of the instruments that they make. It appears as either brown, clear, or green spotting on the surface of the brass. These different colors are grouped together because they all occur at similar locations. Acid bleed is commonly found at areas of the instruments that have been soldered, like joints, tube fittings, and the lip of the horn. The reaction happens much more frequently on trombones than trumpets. While it’s unclear exactly what is causing the reaction, I have been talking to engineers from the company and doing research and testing to narrow down the surrounding theories. Over the next month, I continued to run tests at Tufts University to provide a report about what is causing the reaction. Much of the resources and insights about the reaction from engineers at Conn-Selmer will be crucial in the testing process.

How are trombones made?

Conn-Selmer has acquired several different instrument maker companies as they have grown in the last 100 years. Vincent Bach is one of these companies, with a manufacturing facility located in Elkhart, Indiana. From June 24th to June 28th, I visited the Vincent Bach instrument manufacturing facility as part of my research.

On Monday, June 24th, I traveled early in the morning to start my work at Conn-Selmer. I took a tour of the facility floor in the morning. I was able to see how all parts of the trombones and trumpets are made, including important processes in soldering, cleaning, desoldering, buffing, and baking the lacquer onto the instrument. The part of the production line that I was most involved in was the soldering of the lip of the horn. In order to produce samples similar to the ones made by professional workers, I later spent a good amount of time learning how to use a flame to solder and practicing crafting the lip of the horn.

After the initial tour and getting situated, I got to work on providing several deliverables for the company. I had the chance to meet with all of the engineers and asked them a bunch of questions about what they thought was causing the reaction and about some of my theories about the reaction. Getting to hear from engineers that had many years of experience working with this problem really guided my thinking in what areas needed to be investigated and what parts of my research I could cut out in order to be efficient. I compiled their theories and accounts into one large document where I used prior testing to analyze each theory. The prevailing area of interest is exploring how the soldering of joints affects the reaction. It is theorized that imperfections in the soldering are the main cause of acid bleed, and I am going to be trying to prove this over the next couple weeks.

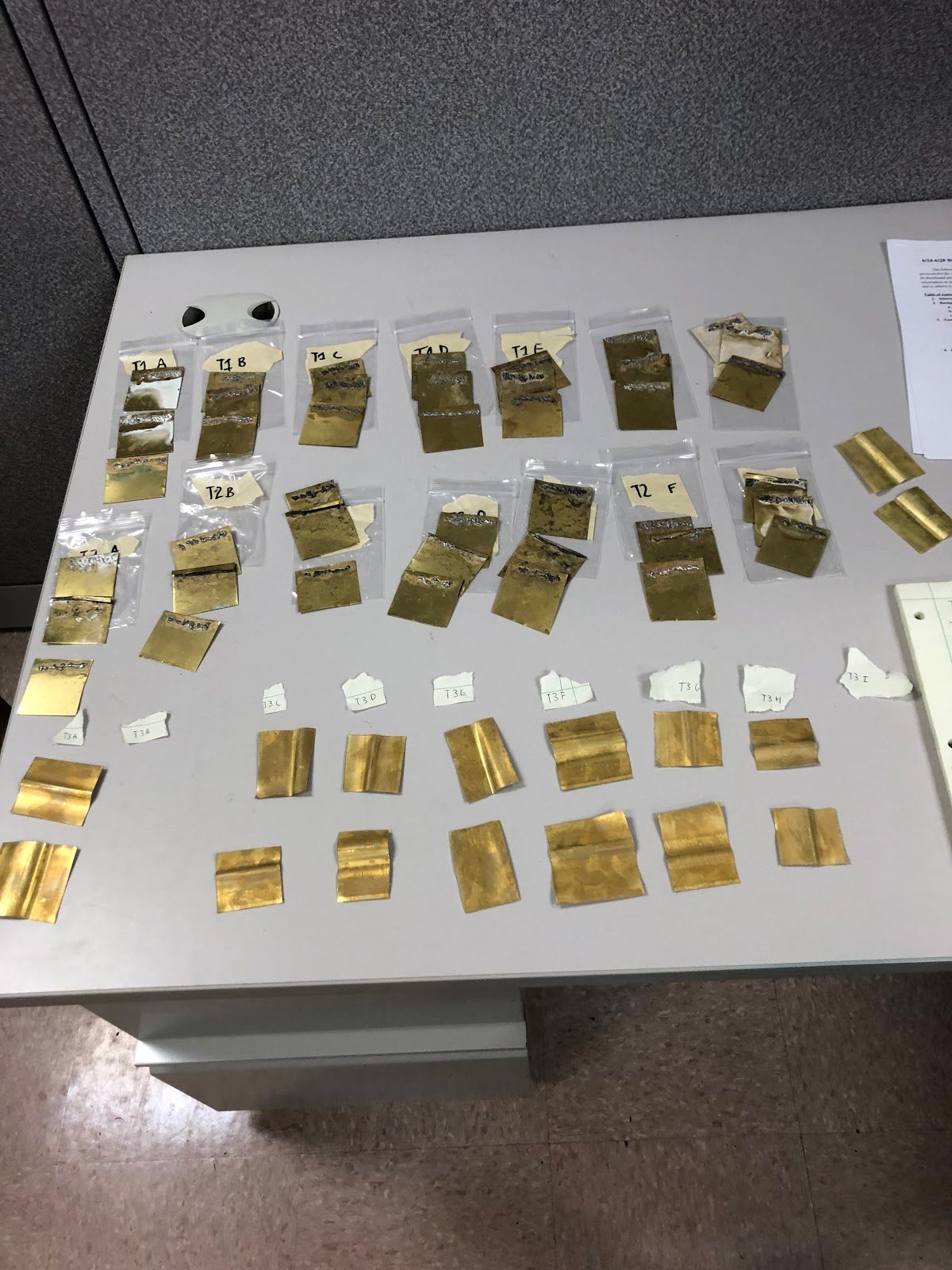

I also spent a lot of time designing tests that can be run at the factory. I used materials and processes at their facility in order to run a test matrix on brass samples that I prepared by hand. In addition to this test, I worked with the engineers at Conn-Selmer to develop an experiment surrounding the soldering process where skilled professionals were developing the samples and running them through the entire production line.

I compiled all of the theories and test procedures into one large report to present at a preliminary evaluation as to what may be causing the acid bleed and how we will proceed to study the reaction going forward. It was incredible how complex the production line at the factory was, and intriguing to see how many complicated operations were performed by workers. It is very important to customers and the quality of the instruments that many of the procedures are performed by hand. I got the chance to see hundreds of skilled machinists performing individual tasks that eventually came together to make some very beautiful instruments. I had a wonderful trip, and I feel very lucky to contribute to finding a solution to the acid bleed problem. I was able to witness the passion that machinists put into their craft and the resourcefulness that engineers used in generating testing methods. I plan on working hard to find a way of eliminating or decreasing the acid bleed on these instruments.

Would be very interested to know what the results of the experiment were, and what solutions were found!

Ditto what Matthew said above.

“It is theorized that imperfections in the soldering are the main cause of acid bleed…”

In the solder itself? In the techniques of soldering? After effects?