The LEGO Foundation Tech and Play initiative connects organizations around the world that are finding ways to make the introduction of technology in classrooms more playful. Tufts Center for Engineering Education and Outreach (CEEO) is collaborating with organizations in partner countries like Rwanda, Kenya, Brazil, and Denmark as a specialist partner in making learning through play with technology more accessible to teachers and in equipping children with the skills to thrive in a technology-driven world.

In addition to the partner countries, it made sense to collaborate with teachers in Nepal because one of our graduate students, Dipeshwor Shrestha, is from Nepal and also a founding member of a Kathmandu-based social enterprise called Karkhana that designs learning experiences for middle school youth. Using existing networks and relations with formal as well as informal educators in Nepal, he invited 22 teachers (2 from public schools, 7 informal educators, and 13 from private schools) to participate in an 8-week engagement program. In this blog post, Dipesh and Sangden (an informal educator, a teacher trainer, and also a participant) share their experiences facilitating/participating in the engagement program.

Current Scenario of Education in Nepal

COVID-19 has changed the current educational landscape, forcing the design of new ways to support learning in formal, informal, and virtual environments. The situation in Nepal is no exception. After the government announced nationwide lockdown in mid-March 2020, every educational institution was left with no choice but to run classes virtually. Although the ordeal of switching to virtual learning came with its own infrastructural challenges, the major challenge was for teachers to adapt to this transition from an in-person mode of instruction to a remote form of instruction.

Looking back at 2020, as educators/researchers/teacher trainers, we can confidently say that we have come very far. Every educational institution and every teacher took this crisis as an opportunity to learn and to adapt to the situation accordingly. In one instance, a school teacher with a decade-long teaching experience was having difficulty in understanding the instructions on how to use Google classroom. He needed a lot of support and step-by-step guidance to go through the different features of a Google classroom. But we were happy to see his excitement to learn something new. He took it up as a challenge, spent a lot of the time learning a new skill, and eventually adapted to the new learning environment. Later, he was able to create a Google classroom on his own and engage his students.

Amidst infrastructural challenges and limited access to resources, teachers have proven time and again to be resilient individuals who are really passionate about teaching and learning practices. When we reached out to teachers and school leaders to participate in the 8-week engagement session, they were excited and open to our ideas and were committed to investing their time and effort in learning new approaches that they could later use in their classroom.

Building Relationships

As with any new community, it took time for everyone to feel comfortable sharing thoughts and ideas with each other. From past experiences, we had realized that it would be more difficult in a virtual setting, and to address this issue, in addition to encouraging the teachers to turn on their videos on Zoom, we tried some activities that we felt were successful in building such relationships.

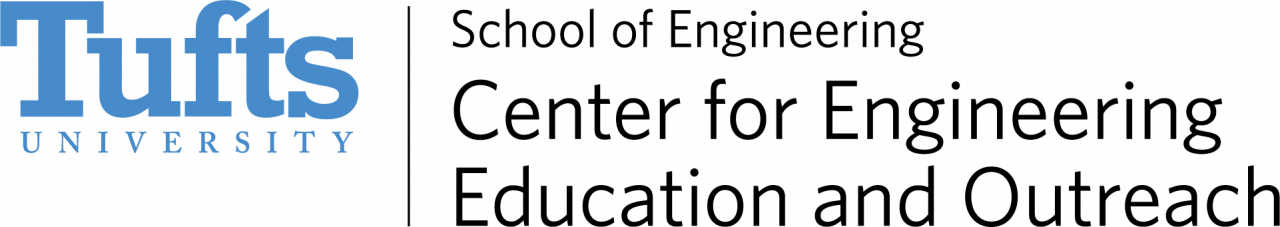

Crazy 4 Representations

In the first session, we asked teachers to come up with representations for the prompt “Draw 4 major events that inspired you to become a teacher.” Some teachers directly started scribbling on a shared Jamboard while others chose to sketch their ideas on a piece of paper which they later uploaded to the Jamboard.

As the teachers took turns to share their stories, we could see commonalities in their experiences. For instance, a couple of teachers had an inspiring teacher or a role model who inspired them to consider teaching as a career path. There were also three teachers whose family members (parents, aunts, or uncles) were educators who encouraged them to become teachers. A few other teachers shared a common hatred of standardized tests. The teachers began to bond with each other through these common experiences and inspirations.

Story Behind Our Names

In the first few weeks, we started with an activity in which 3-4 teachers shared the story behind their names. The teachers could share the story behind the literal meaning of their names, or their middle name or surname, or about who gave them their name, or who they were named after, or about how they got their nickname, or how people mispronounced their name.

I started with my name Dipeshwor, which can be broken down into two root words: “dip” meaning light, and “ishwor” meaning “god,” so when you combine it, it translates to “god of light.” In addition to that, the “wor” at the end of my name is some sort of a family tradition. My father’s name is Maheshwor, my brother’s name is Asheshwor, and my uncles’ names are Jayashwor, Ishwor, Bisheshwor, Siddhishwor, and Shaktishwor. So, if you know someone whose name is ______wor Man Shrestha, it is very likely that that person is a relative of mine.

Other teachers followed, sharing stories behind their names. A teacher’s uncle gave her an English-sounding name, Jennifer (pseudonym) because it was an uncommon name for a Nepali girl. Another teacher’s mom named him Rahul (pseudonym) based on her favorite character from a popular soap opera. Another teacher was named Sabita (pseudonym) because her elder sister’s name was Sunita (pseudonym) and it is a common practice to give names that rhyme to siblings. Sangden grew up believing her dad’s story that her name was a Tibetan word for “a beautiful flower,” but later realized that her dad had made up that story and still does not know the actual meaning of her name. These light-hearted conversations deepened the bonds among the participants and we noticed that they were opening up to each other as the sessions progressed.

Small Break Out Rooms

Based on prior experiences facilitating virtual sessions on Zoom, we planned small breakout room discussions with 3-4 participants in each session. We noticed that in smaller groups, participants were more comfortable interacting and discussing their ideas with each other. One thing that really worked in small breakout rooms was that everyone had their video camera on, which made the interactions richer. Break-out room activities also gave them time to share with each other their backgrounds and experiences of teaching which we think allowed them to get to know each other better as individuals.

Approaches

Novel Engineering

Novel Engineering (NE) is an interdisciplinary approach developed by the Tufts CEEO to teach engineering and literacy to elementary and middle school students which connect storytelling to engineering and making. In Novel Engineering, learners use classroom literature (stories, novels, and expository texts) to identify engineering problems and explore their ideas through design projects to solve these problems. The advantages of such an approach are that learners identify problems on their own, the context of the book offers a way to simulate clients and constraints that real-world engineers wrestle with as they define problems and identify design constraints, learners empathize with characters as clients, and teachers are able to easily integrate NE with existing curricula and customize their approach based on their own goals and comfort level.

The teachers read Muncha, Muncha, Muncha by Candace Fleming (author) and G. Brian Karas (illustrator). First, they identified problems that the characters in the story faced. Then they came up with possible solutions to solve the problems. They then used “found” materials as well as materials in the Karkhana Science kits, to build prototypes of their solutions. In Figure 2, there are some examples of what they ended up making. Jennifer (pseudonym) created a motorized scarecrow (Figure 2, top middle) using a ping pong ball as its head, a medicine bottle as its body, skewers as its hands, and scrap clothes to dress it up. During the sharing session, she also mentioned that when her family members saw what she was working on, they also got really excited and helped her source the materials and helped her build the scarecrow. Similarly, Aakriti (pseudonym) wanted to make an alarm system that would trigger when the bunnies entered the garden but the Karkhana Science kit did not have a buzzer. So, she came up with this clever idea of using a motor (which was a part of the kit) to function as an alarm (Figure 2, bottom right). She fixed a spoon to the motor shaft that would hit another metal object producing a clattering sound. In addition to that, Rahul (pseudonym) utilized prior knowledge in Arduino to build a field scanning setup using a servo and an LED.

After experiencing the NE approach on their own, the teachers then worked in pairs to design a lesson plan which they would test with their students. Three teachers have actually implemented that lesson with other learners.

Photovoice

Photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1997) is an established methodology for studying how youth explore and see the issues facing their communities using photography. Participants are issued disposable cameras (or invited to use digital cameras) and asked to capture images from their community that will help them tell stories of challenges, opportunities, or issues in their local contexts. Participants take photographs and construct narrations of what they see and know about these photographs.

Since the session was virtual, we asked the teachers to upload pictures (on Jamboard) of objects, places, people, or events

- that tell a story about the evolution of your role as a teacher.

- that make you proud of your educational environment.

- in the educational environment that challenge or frustrate you.

- that relate to characteristics of Learning through Play (joyful, iterative, social, actively engaging, meaningful)

- that express the spirit of your daily life

- Your commute to work/school

- Cultural/Spiritual/Social aspects

- Your free time, social/family interactions, and entertainment

In addition to pictures the teachers uploaded to tell a story related to their teaching environment, the majority of the teachers also shared pictures to share what they did in their spare time. We believe this indicated an increasing comfort level with other participants and burgeoning relationships among teachers. Similar to NE, after experiencing the approach on their own, the teachers then worked in pairs to design a lesson plan which they would test with their students. Two teachers have implemented that lesson with their students and shared what their students came up with.

Activities

Synchronous + Asynchronous Engagements

The overall session was designed to include both asynchronous and synchronous aspects of engagement. Besides the 90 minute weekly synchronous meetings, the participants were expected to read research papers, come up with representations to communicate their thinking, figure out new tools, design a lesson plan, or simply reflect on their pedagogical practices, asynchronously, which left plenty of time for synchronous discussions and idea-sharing. In the beginning, many participants had shared their interest in designing their classroom in a blended model, considering the current situation. Later, a couple of teachers shared how they were now open to improving and changing their classroom delivery depending on the interests of the audience/students and that this form of collaboration between participants added new perspectives into designing and facilitating workshops in a virtual setting.

How It Works Diagram

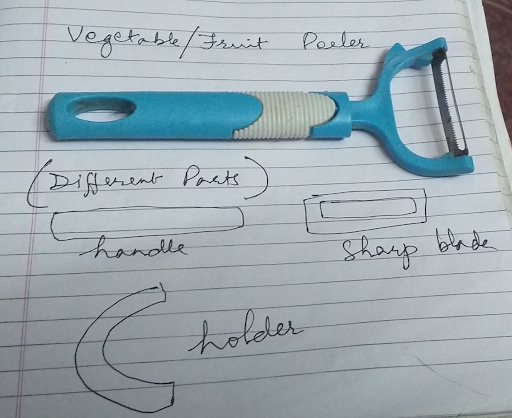

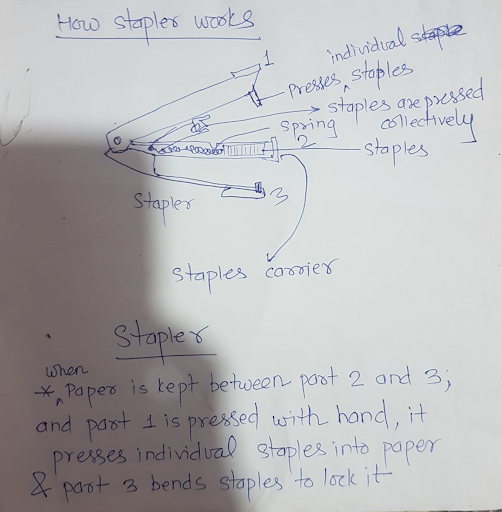

How it Works Diagrams provide an opportunity to explore how a project works. These diagrams elicit reflection as learners try to understand and explain why things work as they do. We provided the participants with different examples that did different kinds of explanatory work, and had a different style. For instance, one explained the mechanism using an illustration, and the other described the “guts” of a project using an artistic photo composition of the components that made the project. In addition to the two diagrams that looked neat and organized, we also included a hand-drawn sketch that looked less refined and less intimidating.

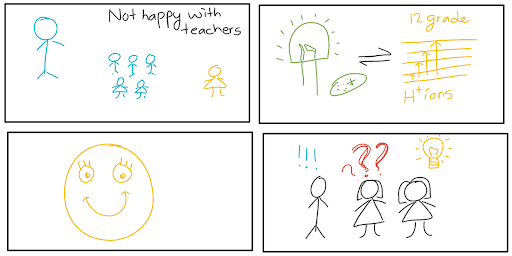

The teachers picked a household object that was near them and they drew a How it Works Diagram to explain the inner workings of those objects. They chose objects like a vegetable peeler, stapler, hand sanitizer, hair clip, Rubik’s cube, mechanical pencil, electronic mosquito repeller, computer mouse, and a watch. The teachers mentioned that they were surprised that even a common household material could provide plenty of opportunities to introduce science and engineering concepts to their students.

Stop Motion Animation

In Week 6, the teachers went through a case study about students trying to make sense of the question “how smell travels” from an amazing resource curated by Tufts researchers called “Students doing science.” The following week, the teachers played with a mobile app called Stop Motion Studio, to make stop motion animations on their own. Ramesh, a science teacher with 20 years of teaching experience, mentioned that although he had come across stop motion animations 10-15 years ago, he had never tried it because he had imagined it would be a difficult and time-consuming process. After creating his first stop motion animation using the mobile app, he shared that he was surprised at how easy and fun it was to make, and that he would definitely try the activity with his students. Figure 5 shows two stop motion animations that the teachers made to represent a scientific phenomenon.

Representations

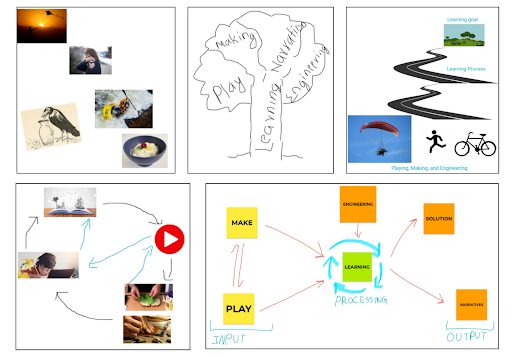

Since one of our objectives was to introduce approaches and ideas around four themes: Play, Storytelling, Making, and Engineering, we wanted to get a sense of how the teachers were imagining the connections among the four themes and how they were related to learning. Anmol (pseudonym) imagined learning as a hike to a mountain (Figure 6, top right) and play, making, and engineering as the different means to reach the learning goal as you would reach the mountain top by the means of gliding, walking, or biking. Keshav (pseudonym), on the other hand, imagined play, making, narratives, and engineering as the branches of a tree that were connected to the broad base of learning. Likewise, Yogesh and Uma (pseudonyms) made sense of the connections drawing parallels between play, making, storytelling, and engineering, and a computer’s Central Processing Unit (CPU), with Play and Making as input, learning as the actual processing, and narratives as an output (Figure 6, bottom right).

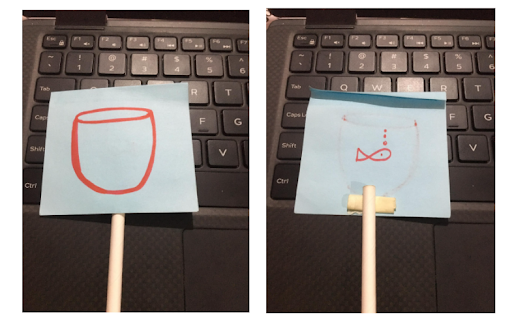

Experience with Making/Building/Creating

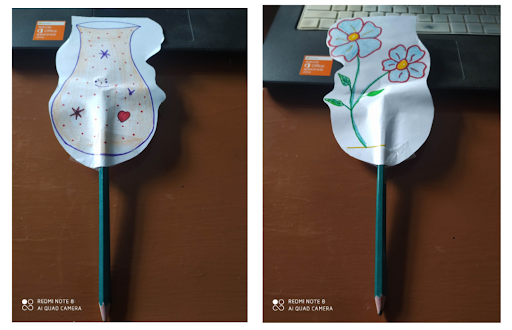

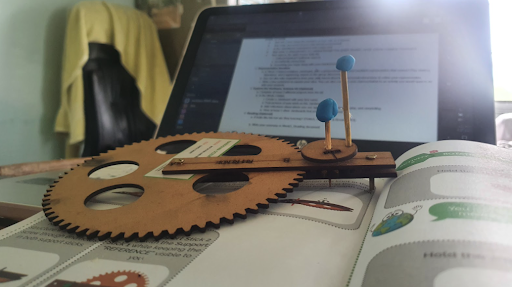

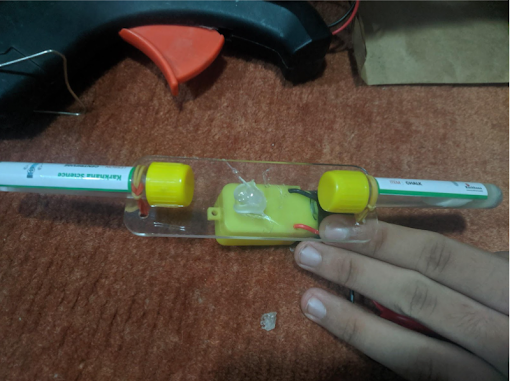

According to the pre-session questionnaires, it was evident that many participants did not have much prior experience with making or engineering. And as Duckworth (1996) in her chapter “The Having of Wonderful Ideas” mentions: “First, teachers themselves must learn in the way that the children in their classes will be learning (p. 9),” one of our objectives was for the teachers to gain familiarity with making, building, and engineering. We started the build activities with familiar materials like paper and scissors to make Pop-up cards. We then integrated some other household materials like pencils, glue, tape, and color markers to make a thaumatrope (Figure 7). Sabita and Mamta (pseudonym) shared that they reminisced playing with materials while they were growing up. Likewise, Anmol (pseudonym) mentioned that he felt like a kid again as he laid all the materials on the table and tried to make something. Later on during the reflection, Sabita shared that integrating hands-on activities into the classroom not only enhances the motor skills but also makes the learning much more meaningful. Gradually, we introduced the teachers to other materials like motors, LEDs, and laser cut acrylic pieces, using the Karkhana science kit (a lag in a bag with curated materials to introduce young learners to hands-on activities that make learning science fun).

We provided each participant with a Karkhana Science kit so that we could engage them in real hands-on experience during this whole program. In the second week, one of the teachers told us that she hadn’t yet opened the bag and was actually waiting on the facilitator’s instruction to explore the kit. Unlike her, a couple of other teachers were curious and explored the kits on their own the moment they received it. We asked those teachers to share what they made with the rest of the group (Figure 8), using the materials in the kit. This encouraged other teachers to explore what was in the bag and to imagine how they could integrate such kits into their classrooms.

Continuation of community of teachers

It is rare to have a support system for teachers in the context of Nepal. Likewise, when it comes to implementation, any new teaching approach or any pedagogical change has to come from a top-down approach. In many cases, teachers rely on a textbook to “teach” students as they are not used to planning a lesson, structuring their curriculum, refining their content, and reflecting on their delivery. The textbooks themselves stay in use for a long time with zero reviews or refinements. Unlike some of those teachers, the teachers who participated in our sessions were open to new ideas and were willing to bring changes to their classrooms. We hope that they will inspire other teachers to move away from textbook teaching to integrating approaches like Novel Engineering and Photovoice in order to engage their students in meaningful ways.

With the success of the 8-week engagement, we wanted to keep this community alive. We hope this community will provide the teachers with a platform where they can come together, support each other, share lesson ideas with one another, share their stories of failure and success, share reflections, and receive feedback on their work. We are excited that 16 out of the 22 teachers have shown interest in keeping the community alive. Last week, two teachers took the initiative to design and deliver a 90-minute session on Scratch for the rest of the teacher community. Likewise, two other teachers have started a critical reading group and have chosen to read Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste as their first book. We are also planning to expand our community by inviting other teachers and educators within our network and beyond. More updates will follow once in-person classes resume, and the teachers implement some of these approaches in their classrooms.