By Mitchel Resnick

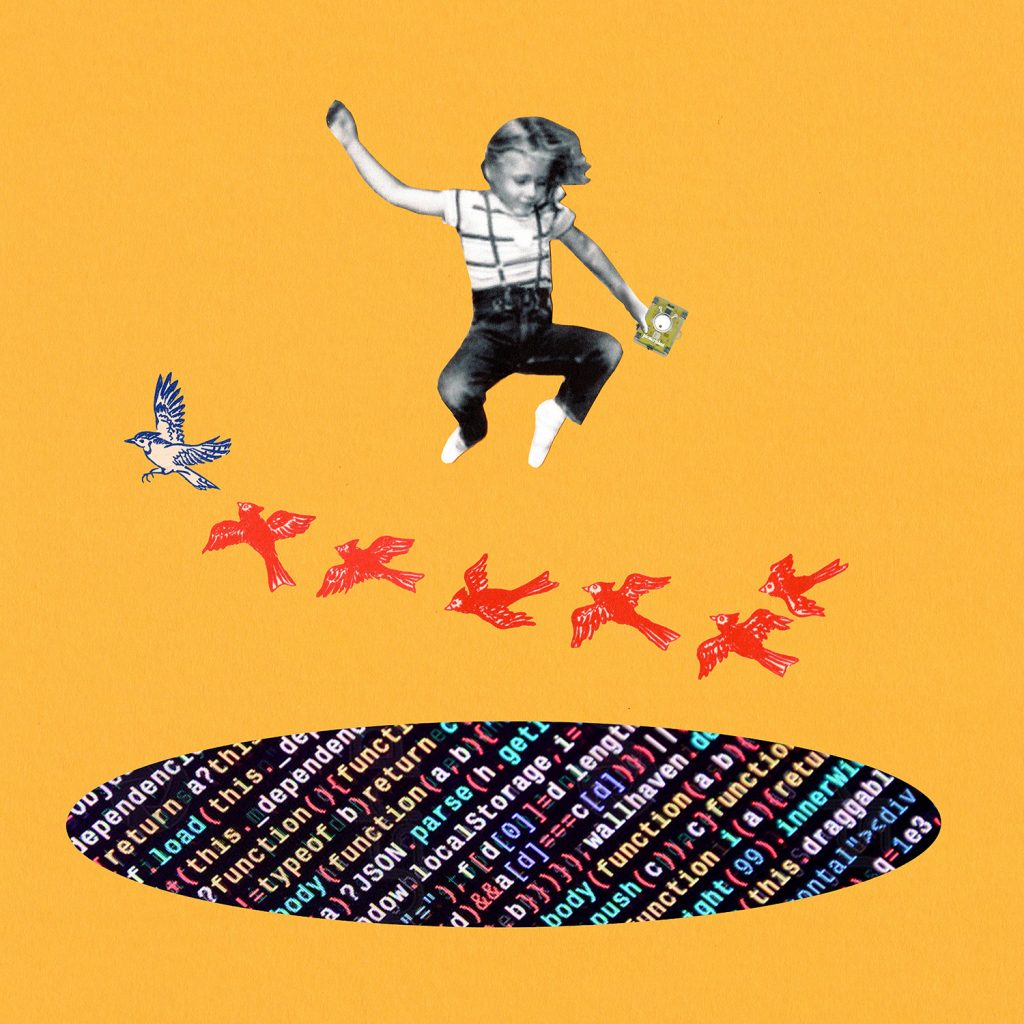

Illustration by Ellen Dubreuil

Editor’s Note:

Our concern that so many children today are disconnected from nature has given rise to blaming disconnection on technology. But as Mitch Resnick explains in the following article, blanket condemnation of technology overlooks the opportunities for children and youth to use new technologies to connect to nature in deep and meaningful ways – ways that we need to understand and support.

In recent years, a growing number of educators and psychologists have expressed concern that computers are stifling children’s learning and creativity, engaging children in mindless interaction and passive consumption. They have a point: today, many computers are used in that way. But that needn’t be the case.

In my research group at the MIT Media Lab, our goal is to develop technologies that follow the tradition of paintbrushes, wooden blocks, and colored beads, expanding the ways that children can explore, experiment, design, and create. In our research, we have found that children’s best learning experiences come when they are actively engaged in creating things and expressing themselves, so we develop technologies that children can use like traditional craft materials, for experimentation and expression.

For example, we have developed “programmable bricks” by embedding electronics inside traditional LEGO bricks, so that children can create not only structures, but things that move, react, and interact. One version is called a Cricket, and children have used it to create their own interactive sculptures, musical instruments, and science investigations. Let me share an example involving an eleven-year-old named Jenny.

Jenny loved watching birds, so when she was introduced to the Cricket, she decided to use it to build a new type of bird feeder. With the Cricket, Jenny figured she could build a new bird feeder that would collect data about the birds that landed on it. Jenny started by making a wooden lever that served as a perch for the birds. At the other end of the lever, Jenny attached a touch sensor consisting of two paper clips. She built a motorized LEGO mechanism that moved a small rod, and mounted the mechanism so that the rod was directly above the shutter button of the camera. Jenny wrote a simple program for the Cricket so that it waited until the paper clips were no longer touching one another (indicating that a bird had arrived), and then turned on the motorized LEGO mechanism, which moved the rod up and down, depressing the shutter button of the camera.

After finishing the first version of the bird feeder, Jenny recognized a problem: If a bird were to hop up and down on the perch, the bird feeder would take multiple photographs of the bird. Jenny added a wait statement to her program, so that the program would pause for a while after taking a photograph. This ability to modify and extend her project led Jenny to develop a deep sense of personal involvement and ownership. Jenny cared about her bird feeder in large part because she had designed and built it. The “fun part” of the project, she explained, “is knowing that you made it; my machine can take pictures of birds!” [emphasis hers].

Of course, the idea of mixing play, technology, and learning is hardly new. In establishing the first kindergarten in 1837, Friedrich Froebel used the technology of his time to develop a set of toys (which became known as “Froebel’s gifts”) with the explicit goal of helping young children learn important concepts such as number, size, shape, and color. Other educators, such as Maria Montessori (1912), have built on Froebel’s ideas, creating a wide range of manipulative materials that engage children in learning through playful explorations.

More recently, there has been a surge of computer-based products that claim to integrate play and learning, under the banner of “edutainment.” But these edutainment products often miss the spirit of playful learning. Often, the creators of edutainment products view education as a bitter medicine that needs the sugarcoating of entertainment to become palatable. They provide entertainment as a reward if you are willing to suffer through a little education. Or they boast that you will have so much fun using their products that you won’t even realize that you are learning – as if learning were the most unpleasant experience in the world.

The example of Jenny and her bird feeder offers a very different approach. I see it as an example of playful learning, as opposed to edutainment. The terms play and learning (things that you do) offer a different perspective from entertainment and education (things that others provide for you). The phrase playful learning, compared to edutainment, conveys a stronger sense of active participation. It might seem like a small change, but the words we use can make a big difference in how we think and what we do.

Despite numerous examples like Jenny and her bird feeder, many people continue to view digital technology in opposition to creative learning, rather than a new way to support it. Let me end with a story of a visit I hosted from three leaders of an organization focused on nurturing children’s imagination and creative abilities. The organization had written reports expressing concern about children’s use of digital technologies, and I shared many of their concerns. I looked forward to showing them how some technologies, rather than stunting children’s imaginations, could actually foster and support the development of their creative thinking and creative expression. But after I showed the visitors Jenny’s bird feeder, and told them the story of how Jenny had built and programmed it, one of the visitors turned to me and said: “Don’t you think it’s a problem to take children away from creative play experiences?” The visitor saw the project using advanced technology and assumed the child could not have been doing anything creative.

We need to move away from generalizations about all computers or all technologies and consider instead the specifics of each technology and the context of its use. Some technologies, in some contexts, foster creative thinking and creative expression; other technologies, in other contexts, restrict it. Rather than focusing on the division between techno-critics and techno-enthusiasts, we need to focus on the difference between activities that foster creative thinking and creative expression (whether they use high-tech, low-tech, or no-tech) and those that don’t.

*This article is a shortened version of Mitch Resnick’s seminal article, “Computer as Paintbrush: Technology, Play, and the Creative Society” Singer, D., Golikoff, R., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (eds.), Play = Learning: How play motivates and enhances children’s cognitive and social-emotional growth. Oxford University Press. 2006.

Mitchel Resnick (@mres), is LEGO Papert Professor of Learning Research at the MIT Media Lab. His research group develops new technologies and activities to engage people (especially children) in creative learning experiences.