To start the year: are food choices predictable?

Long post alert!

The short answer to the title question is: Yes, some of the time.

The long story starts with the opening phrase of the first modern textbook on principles of economics. That line, from Alfred Marshall in 1890, defines economics as the study of people’s “actions in the ordinary business of life”. More than a century later, we’re still drawing some of the same diagrams from that book, applying a few basic principles to explain, predict and evaluate people’s choices.

Economists study ordinary life using well-established methods, but many students find those methods to be profoundly weird. For example, economists take it for granted that people have at least some stable preferences, from which we can interpret their level of well-being. Are students willing to go there, based on their prior beliefs before the first day of class?

This year I am testing the use of instant polling, and thought I’d try a warmup exercise before the first class to get at the wide variety of perspectives that students bring — starting with the most basic question of whether our choices are even predictable enough to explain.

To reveal students’ baseline beliefs about decision-making, I created a survey asking them what fraction of last year’s choices we “regret and would do differently” if we “had the same options and circumstances as last year”.

This question reveals the degree to which people think our actions can be predicted at all from year to year, based on data we might collect about past choices and their circumstances. I wanted to compare food choice to other decisions, and to compare levels of regret about meals at home versus food choices in restaurants. (More about that later.)

If peoples’ choices are predictable, they might also be ‘rational’. To the extent that we are predictably irrational, we can learn from our mistakes and not make them again. And we might also be entirely predictable but lacking free will. Economics traditionally focuses on ‘rational’ choices that we don’t regret and wouldn’t change, adding insights from psychology in the vast field of behavioral economics, and collaborating with people from other fields to explain all kinds of behavior like we do in the economics of nutrition.

Much of life — including dietary intake — may be entirely random, or entirely deterministic. Economists are interested in those actions which are actually choices, because those actions might reveal stable preferences. Only when preferences are stable can we explain and predict choices, and allow outcomes to be ranked in terms of how far people get towards the outcomes they consistently prefer.

The kinds of choices I wanted to include in my survey, in addition to food choice, concern other decisions we make frequently with varying degrees of regret and changing our minds. My highest priority was to include a question about gifts to others, to be sure that students don’t confuse being ‘rational’ with being selfish. (Econ 101 models often avoid the topic of generosity, but that’s just because the math is tricky.) I also wanted to include once-only experiences, like movies and live shows that we don’t know much about until it’s too late to change, and also alcohol since it’s entire purpose is to blur things. The final list, in alphabetical order, was choices about alcohol, clothing, food at home, food in restaurants, gifts, and travel.

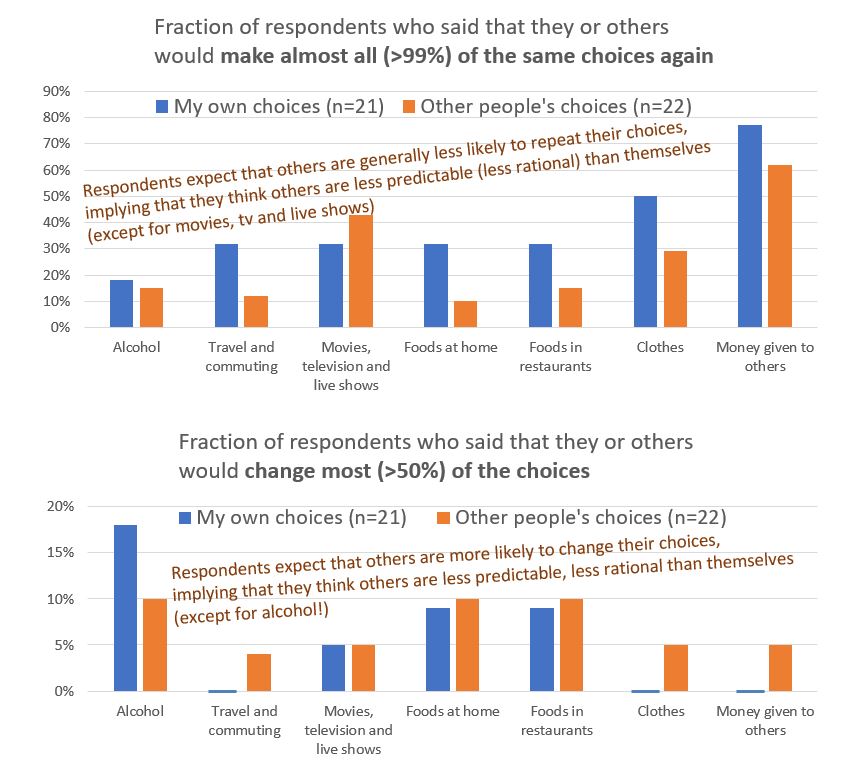

The survey was designed in part to reveal whether students thought differently about their own choices than about the choices made by other people. Perhaps there would be a kind of self-confidence bias, by which students believe their own decisions to be more predictable than other peoples’ choices. A belief in “rationality for me but not for thee” would myopic but understandable: since we know more about our own circumstances than those of other peoples, it’s hard to see why others behave as they do. Anyhow I was too rushed to register my analysis plan with AsPredicted and in any case I want to be clear that this poll was not human subjects research — it was done purely for teaching purposes in this class, and its sample size is too small to be generalized.

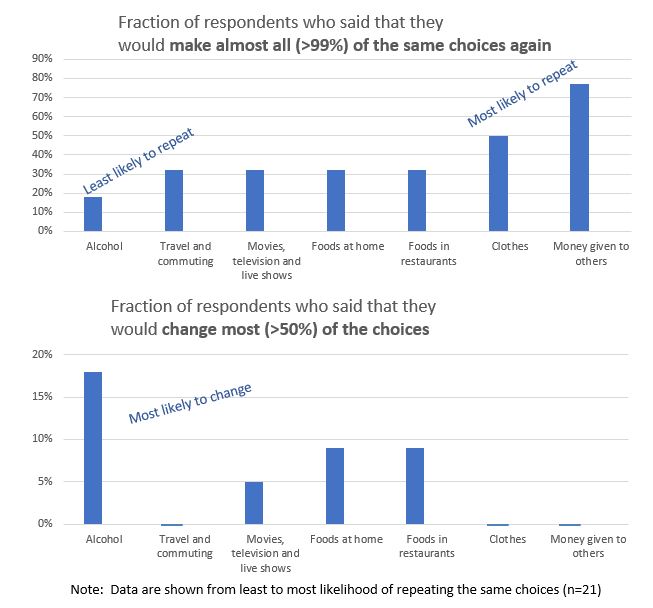

To keep the survey short and avoid any kind of priming, confirmation bias or social desirability bias, I randomly assigned students to one of two nearly identical surveys. One asked “for each category below, thinking about your own actions, please guess what fraction of recent choices you regret and would do differently. “, and the other asked the same question but “thinking about other people like you“. I made it a series of 7 multiple-choice questions, asking if they expected themselves or others to “make all the same choices again“, “change less than one percent (<1%)”, “change less than five percent (<5%)”, “change less than half (<50%)”, or “change most (>50%)” of their own choices. I had to gather responses to make charts before class, by which time there had been about 85% response rate with 21-22 responses in each arm. You can see the whole questionnaire and all responses here.

To summarize results, I’ll focus on the extremes: those who said choices are almost entirely predictable, meaning that they’d change less than 1% or make all the same choices again, versus those that would mostly change (>50%).  Among the students who were asked about their own choices, about a third felt that their food choices are almost entirely predictable, and about a tenth said they would change most of their food choices. Percentages were the same for food at home and in restaurants, which was contrary to my expectations: personally, I almost never regret what I eat at home, but do so fairly often when eating at restaurants. Maybe students eat in restaurants a lot more routinely than I do, so they know what they’re getting.

Among the students who were asked about their own choices, about a third felt that their food choices are almost entirely predictable, and about a tenth said they would change most of their food choices. Percentages were the same for food at home and in restaurants, which was contrary to my expectations: personally, I almost never regret what I eat at home, but do so fairly often when eating at restaurants. Maybe students eat in restaurants a lot more routinely than I do, so they know what they’re getting.

Respondents expected others’ choices to be less consistently predictable than their own, although responses for movies and shows were similar, and the big exception was alcohol: more respondents thought that they would learn and change their own drinking choices than that others would learn and change. That’s a particularly good example of self-confidence, although maybe just a January effect.

We’ll discuss these results in class tomorrow, and learn more throughout the semester. For now, some takeaways:

(a) Many students think their own choices are likely to change and therefore hard to predict, and an even larger number believe that other peoples’ choices will change, even if their options and circumstances stay the same. Both are probably correct, although I’ll do my best to teach techniques that explain and predict a larger fraction of peoples’ choices.

(b) Food choices are in the same ballpark as other things. Food is not unique in being subject to random (or seemingly random) whims and fads that change without explanation.

(c) I was very surprised by similarity in responses about food at home and in restaurants, for the reasons mentioned above, and also surprised by respondents’ confidence in their choices about money given to others. Personally, I second-guess my own charitable donations all the time: I’m very confident about the effectiveness of some donations, while others are just a guess which I change from year to year. This is a good example of the final takeaway:

(d) There is a lot of heterogeneity here, with very different answers from different respondents. In food choice, for example, a third would repeat almost all their choices while a tenth would change most of them. That’s why business schools teach marketing, so companies can spot their loyal customers and also identify people who might switch. I hope my economics class works kind of like that, serving all kinds of students in different ways.

(e) For teaching, I’m still experimenting with PollEverywhere but so far it works as advertised and is super fun. I’ve long done instant polls by asking students for hidden hand signals in front of their chest, but then choices are limited to a thumbs-up, stop or number of fingers, and only I can see their answers. Also difficult for me to count answers quickly. Asking students to respond on their touchscreens is much better and has led me to relax my previously draconian no-devices policy (but only on phones – still no laptops, so notetaking is only on paper). And randomization of polls to compare responses, as in this pre-class survey, seems very promising. If you’re interested, send me email or respond on twitter:

Are food choices predictable?

Our @TuftsNutrition students have opinions:https://t.co/xb0ToFPTRP

— William A. Masters (@wamasters) January 21, 2019