The theme of this year’s American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) meeting in Boston was “Serving Society through Science Policy.” As we move through the first few months of a new administration, this gathering could not have been more timely. While this conference is diverse with topics ranging from gene editing to criminology, the undercurrent of the meeting was anxiety over what will happen to research under the Trump administration.

What is science policy even? Most in this audience probably think of it as how much money research gets budgeted and occasional rule changes on whether fetal stem cell research can occur. Generally, science policy is the set of federal rules and policies that guide how research is done. Science policy can be split into two general frameworks: policy for science and science for policy. These can often feed into each other. For example, policy for science provides funds for climate research. The data and conclusions derived from that research could then inform new climate related policies. That would be science for policy. While science itself is an important input into the whole process, other considerations such as economics, ethics, budgets and public opinion are also inputs. As a scientist who considers science as a method of interpreting the world, my biases had not let me consider non-science inputs for science policy decision-making. It may seem obvious to some, but it was illuminating to realize that other concerns can be just as valuable and legitimate.

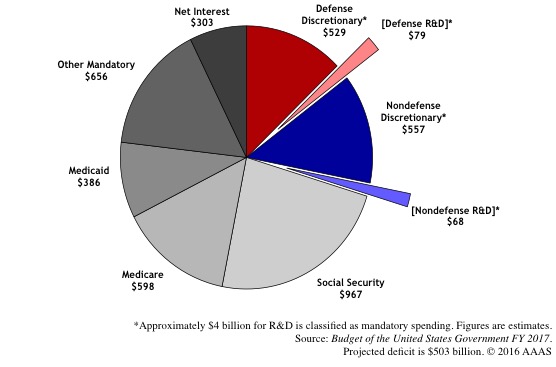

As funding is a major reason scientists are concerned, I was happy to learn a lot about the place of research in the federal budget. There are some out there who believe that research in Boston will be fine no matter who is in charge because of all the industry science in the area. It’s true; around two-thirds of research and development is funded by industry. However, industry is mostly concerned with development. Basic research is primarily funded by federal money. The federal budget is divided into mandatory spending and discretionary spending. Mandatory spending does not require congress to act for programs in it to be funded. These include the entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Dr. Josh Shiode, a Senior Government Relations Officer from AAAS, informed us that entitlement programs are considered “third-rail” discussions by lawmakers, meaning if you touch them, you die (an electoral death). In contrast, discretionary spending requires Congress to actively fund. Most of research and development spending falls into this category.

Due to changing (aging) demographics, the percentage of the budget that goes towards mandatory spending has been steadily increasing. 50 years ago, we spent around 30% of the federal budget on mandatory spending and now we are up to 70% and increasing. Research and development generally gets around 10-12% of the remaining budget left for discretionary spending. Traditionally, increases in discretionary defense spending will correspond with a parallel increase in nondefense discretionary spending. The Trump administration has proposed increases in military spending. Given likely tax cuts and reluctance to make changes to entitlement programs, it is unlikely nondefense discretionary funding will fare well. The good news is major research programs like the BRAIN Initiative, Precision Medicine Initiative and the Cancer Moonshot were funded through the bipartisan 21st Century Cures act during the lame-duck session. While NIH and biomedical research will likely have diminished profiles during this administration, both parties are against Alzheimer’s, diabetes and cancer. What is less clear is how research performed by the EPA and Department of Agriculture will fare although initial reports are grim. Finally, repeal of the Affordable Care Act will have rippling effects, as many research universities are also providers of healthcare. It is clear that there will be a shift in culture. Under President Obama, science was elevated and scientists were regularly consulted. As former senior science adviser to President Obama John Holdren said: “Trump resists facts he doesn’t like”.

There is reluctance for some scientists to get involved in the political theater, as some believe science should be apolitical. I would argue that science is already political as science can dictate policy and policy can dictate science. What science is and should be is nonpartisan. No party has an inherent monopoly on being allies of science and scientific thinking. So what can scientists do? All politics is local and personal. The majority of Americans say they don’t know a scientist. This is an easy thing to work on. Make sure you introduce yourself to others! Visit your lawmakers and let them know that you are funded by federal money. Politicians are most concerned about their own districts and so if you’re a transplant, you likely have connections to more than one district. Try to build a relationship with him or her by seeing if you could help with anything. Figure out if you can help your local community with anything by serving on committees. Speaking of committees, know what committees your representatives are on. When communicating, think carefully about what words you use. Former U.S. Congressman Bart Gordon opined that he never called it climate change. Instead, he called it energy independence. While branding may sound like a trivial thing to worry about, targeted story telling is extremely important. We would love for our data to speak for itself but people connect best to stories, especially ones concerning things they can relate to or care about.

If you’re interested in science policy, there are a number of good resources available to get better acquainted. The Engaging Scientists & Engineers in Policy (ESEP) Coalition has a wealth of information and resources on their website (http://science-engage.org/). In fact, they host a local monthly science policy happy hour to network and engage those interested in science policy. If you are interested in learning more about the R&D budget, AAAS has an excellent resource with analyses of federal research and development funding (https://www.aaas.org/program/rd-budget-and-policy-program). There you can also find their data dashboard to look at funding for specific agencies for different periods of time.

very nice article, thanks for sharing.