The main responsibility of a biomedical researcher is to produce novel, trustworthy science that will improve human health. We may not be doing enough towards this goal, however, if we consider our research results to be our only impact on the human condition. How we conduct our research is just as critical as the results of our research, especially when it comes to the environmental footprint that research laboratories leave behind on university and medical campuses.

In 2013, Tufts University published a campus-wide report to assist the university in building a sustainable future. Working groups focused on three relevant sustainability areas—energy and water use, waste management, and greenhouse gas emissions—to develop actionable goals for reducing Tufts’ environmental impact. Regarding how laboratories and medical facilities factored into this impact, all working groups came to the same conclusion: “[these spaces were] singled out…as the greatest source of opportunity for increased sustainability across all Tufts campuses due to their large production of waste and heavy use of water and energy.”

Tufts is not the only university facing these issues. Harvard University labs consist of 20% of physical campus space but account for 44% of their energy use, and MIT labs take up less than a quarter of campus space but account for up to two-thirds of their energy use. So, if scientists like to talk the talk when it comes to best practices in advocating for governmental and community support of sustainable practices, how can we commit to similar support within our own institutions?

Many universities, including Tufts, have implemented Green Labs initiatives in order to develop environmentally friendly research laboratories using a classic sustainability framework: reduce, reuse, recycle. Based on resources from Tufts’ Green Labs Initiative and similar programs at other institutions, here are some starting points for making laboratories and research facilities more sustainable.

REDUCE

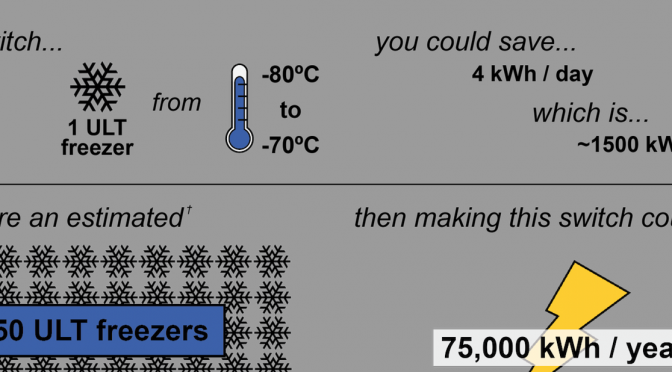

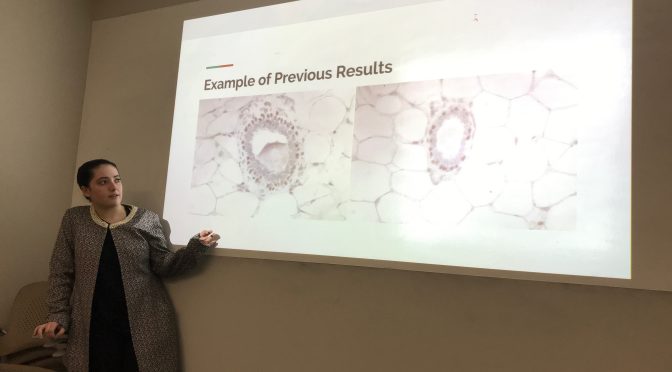

Energy: Labs can significantly reduce energy usage by maximizing the efficiency of their ultra-low temperature (ULT, or -80°C) freezers, as in one year, a single ULT freezer uses the same amount of energy as an average American household. Frequent de-icing, regular upkeep, and maintained organization all decrease the amount of work and time (and thus energy) required by freezers to decrease temperature to the set point. To encourage these approaches, Tufts joined the International Freezer Challenge in 2017, which “rewards best practices in cold storage management”. Of note, three Sackler labs–the Munger lab, the McGuire lab, and the Bierderer lab–participated. Additionally, a less universally advertised, but possibly more effective, approach to reducing energy usage by ULT freezers is changing their set temperature. The University of Colorado at Boulder has accumulated a significant amount of information demonstrating that maintaining ULT freezers at -80°C may not be necessary, as many sample types are capable of being stored at -70°C without any significant loss of quality. Though seemingly trivial, this ten degree difference has huge implications for lowering energy usage , which also translates to reduced energy costs (Figure 1). By rough estimation, Tufts could save close to $50,000 per year on electricity if all ULT freezers in Jaharis, M&V, Stearns, South Cove, and Arnold were adjusted from -80°C to -70°C.

Figure 1. Yearly energy expenditure & cost savings for ten-degree increase in ULT freezer temperature.

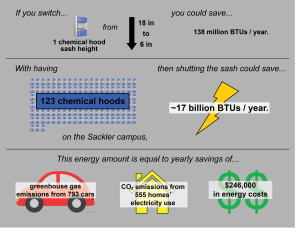

Closing and/or turning off chemical fume hoods when not in use also mitigates electrical expenditure. At the Medford campus, undergraduate student Emma Cusack led a “Shut the Sash” initiative last year in order to reduce energy use and cost. Based on consultations with the Tufts’ Office of Sustainability about her work, it is estimated that lowering sashes of all 123 chemical hoods on the Sackler campus from 18” to 6” when not in use would result in yearly energy expediture savings of around 40,000 kWh and energy cost savings of over $200,000.

Figure 2. Yearly energy expenditure & cost savings for reducing sash height of chemical hoods.

Lastly, powering down non-essential lab equipment overnight and incorporating timers into power sources are also simple but meaningful methods of lowering energy usage. The latter method is especially helpful to maintain convenience along with energy efficiency, as incubators and dry ovens are shut off overnight but can still be ready-to-use upon arriving in lab, for example, if set to turn on in very early AM.

Water: A traditional autoclave requires 45-50 gallons of water per minute when in use, and this massive usage is due to the need for continuous addition of water for cooling steam condensate before draining into sewers. Equipment like Water-Mizers use real-time monitoring of drain temperature to add water for cooling only when needed, reducing water usage by at least half. Also, being mindful of when sterilization is actually required for equipment and using dishwashing services as an alternative also contributes to lowering water usage.

Within labs, addition of low-flow aerators to faucets and switching vacuum sources for aspirators from faucet-style to vacuum-style can also can significantly reduce water usage. Finally, being conscious of when it is really necessary to use distilled or deionized water, as the process wastes water that does not pass the filtering thresholds, can also contribute to making water usage by labs more efficient.

REUSE

Materials: Styrofoam shipping containers and freezers packs can accumulate quickly in labs, given the frequency at which supplies are ordered and received. However, they are not necessarily easy to get rid of in sustainable ways. Many labs end up reusing some fraction of the styrofoam boxes and freezer packs they receive for experiments, which seems to be the most common and easily practiced alternative to throwing these shipping components away.

RECYCLE

Materials: Another approach for sustainable disposal of styrofoam and freezer packs is recycling them. A handful of life sciences companies do sponsor recycling programs for styrofoam containers, including Sigma-Aldrich, Qiagen, and New England BioLabs (which has run such a program for over thirty years), but most companies do not, given the cost of such programs. Alternatively, for-hire companies specializing in styrofoam recycling can be contracted by universities, but again the associated cost can be a deterrent. Even rarer are return programs for freezer packs, as the combination of contamination concerns and the cost of re-sterilizing seems to discourage their implementation.

The amount of plastic materials that biomedical research labs use are also quite high, though recycling used materials such as pipette tips, serological pipettes, conical tubes, or microcentrifuge tubes is often not convenient or feasible due to biological contamination. However, containers for materials (i.e. cell culture media bottles, pipette tip boxes) can be sterilized and disposed of much more easily. In the case of pipette tip boxes, several companies–such as Fisher Scientific, USA Scientific, Corning, and VWR–do sponsor programs where discarded boxes are collected or received via mail for recycling.

While achieving greener laboratories first requires implementation of sustainable practices like those listed above, the success of such efforts ultimately depends on institutional support and researcher engagement. Even if such resources and programs are offered by companies or research institutions, scientists need to be made clearly aware of their existence to take advantage of them. Accordingly, university- or departmental-level promotion of and encouragement for sustainable practices could substantially increase researcher interest and participation. Implementing reward-based systems, including financial incentives, for labs that ‘go green’ could also help motivate investigators to commit to practicing sustainable science.

In being more conscious of the environmental footprint that biomedical research leaves behind, scientists can clean up our own backyard and stand on firmer ground when encouraging others to do the same.

Thank you to Tina Woolston and Shoshana Blank from the Tufts Office of Sustainability and to Stephen Larson and Josh Foster from Tufts Environmental Health & Safety for providing information and resources on chemical hood numbers, energy usage, and costs.

Resources

Tufts University: http://sustainability.tufts.edu/get-involved/tufts-green-labs-initiative/

http://sites.tufts.edu/tuftsgetsgreen/2017/07/28/the-green-labs-initiative-an-overview/

University of Colorado: https://www.colorado.edu/ecenter/greenlabs

EPA Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator: https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator

Laboratory Fume Hood Calculator: http://fumehoodcalculator.lbl.gov/index.php