What she loved; life; London; this moment of June

By John Lurz, Associate Professor of English

These days, there’s a lot of texting going on among my friends and family, near and far, as we reach through all this new social distance. It can be a challenge to thumb the complexity of one’s quarantine experience into that abbreviated format – in part because, with the condensation of our actions and affairs to the confines of our homes, this experience is at the same time so simple. Facing this challenge in a fleeting text conversation with a friend in New York, I found myself plainly and tersely writing, “I’m having a lot of feelings about this whole thing, but my books are helping.” And I’ve come back to that thought over and over since I wrote it, its intimation of another kind of textual relationship that this moment is laying bare.

The books that I keep turning to for help are not anything special or particularly addressed to a pandemic. Rather, they are the simple ones that, because I teach and write about them, I’m always contemplating. Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, for instance, has been my favorite novel in English for at least fifteen years, one that shows up on my course syllabi semester after semester. But its plot about an upper-class woman planning a party as England recovers from World War I has taken on new significance in these new circumstances. It’s not just that I would dearly like to go to a party right now (wouldn’t you?), but it’s also the way that Clarissa Dalloway’s internal musings as she goes about her errands verbalize some of the “feelings” about this moment that I simply have not been able to fully to articulate for myself.

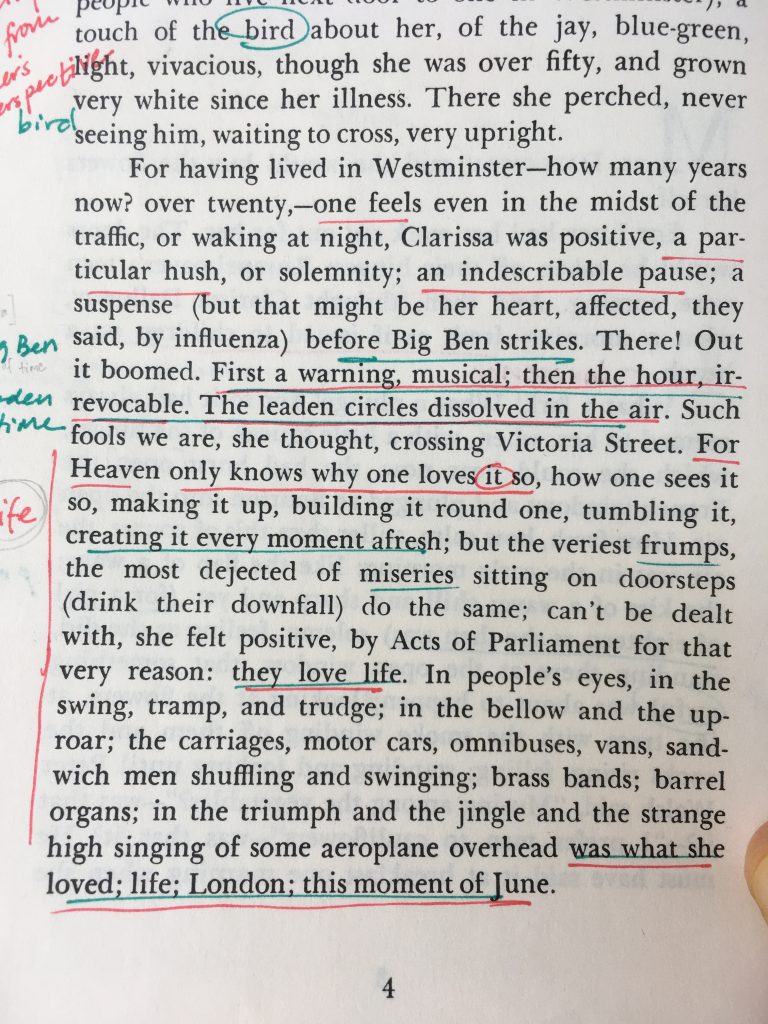

Opening the novel with a simple walk through the capital to famously “buy the flowers herself,” Clarissa drinks in its energy and vitality, which are made all the more apparent to her in the wake of both the war’s cataclysmic carnage and her own individual bout (which I always forget) with the influenza that ravaged the world in 1918. In a description of the city that hits you with the full force of Woolf’s intoxicating lyricism, I find a feeling that I’ve faintly sensed on the underside of my recent anxiety and fear:

…in the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment of June.

Again, “what she loved; life; London; this moment of June” – in its simplicity, this sentence proclaims some of the motivation for our generalized worry in the face of COVID-19, namely a love of life and all its quotidian commonplaces. The steady throb of the phrasing that mimics the sensory barrage of urban experience also underscores the ephemerality of such simple experience, the inescapable evanescence out of which life itself is made. As these lines give voice to something like the gentle heartbeat of the world, I find a vibrancy inseparable from fragility and see how our fear for life is, in a sense, our love for it turned inside out.

These are some of the feelings that I wanted to text my friend about; they are what my books are helping me to bear in mind; and they are what I’m “texting” to you here as a way to simply bear this experience at all.