Bad Eggs: A Darwinian Approach to Ovarian Cancer

by Natalie Perlov, Jamie Tebeau, and Michelle Ysrael

Introduction

While modern medicine may seek to understand the etiology and manifestations of illness, Darwinian medicine examines the evolutionary factors that have maintained disease in the human population. This evolutionary approach may provide novel insights to modern afflictions, such as ovarian cancer. Our research identified three main areas of interest: Incessant Ovulation Theory (IOT), inflammation, and other evolutionary change. In this blog post, we will explore these three key examples.

Incessant Ovulation Theory

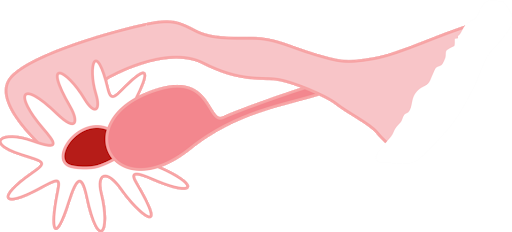

IOT holds that increased ovulatory and menstrual events may increase the risk of gynecological malignancies due to accumulated cell mutations. Evolutionarily, our ancestors were not ovulating and menstruating as much as the modern woman due to earlier and more frequent pregnancy and longer breastfeeding periods. The risk factors for ovarian cancer correlate with a greater number of ovulatory events, such as having fewer children and later onset of menopause, while the protective factors correlate with fewer ovulatory events, mainly having more children and taking combined oral contraceptives.

Inflammation

The burst of epithelial cells during ovulation is extremely inflammatory and results in the release of inflammatory mediators like cytokines and chemokines. Cells that are repeatedly exposed to inflammatory environments are more likely to undergo mutagenesis and increased cell proliferation. One evolutionary consequence of the development of menstruation is reflux of blood that can cause an inflammatory response in the uterus and ovaries. The blood that backwashes into the ovaries contains genotoxic elements that can encourage cell mutations and the proliferation of cancerous cells. Increased menstrual events may also be linked to the development of more aggressive placentation. As human brains evolved to be bigger, fetal demand for maternal resources increased. The genetic interests of mother and fetus were sometimes at odds: mom needed to conserve resources for future offspring, whereas the fetus wanted to capitalize on all that mom could provide. As a result, menstruation may have evolved to allow mom to regain some autonomy in this process.

Evolution

Other evolutionary events may shed insight into ovarian cancer. The evolution of concealed ovulation, the lack of major perceptible change in the female during her fertile period, may be one of them. Vervet monkeys, which are also concealed ovulators, have decreased rates of infanticide compared to their primate relatives, possibly because males are unable to ascertain the paternity of offspring. With males unable to monopolize fertile females (since males could not predict which females were fertile), there was less sexual competition and greater opportunity for cooperation. In humans, we hypothesize that concealed ovulation may have evolved to increase social cooperation, which was necessary to provide enough calories and protein for a growing brain. Since ovulation was concealed, increased frequency of ovulation was necessary to ensure conception, resulting in what we now refer to as “incessant ovulation.”

The simple layout of human reproductive anatomy – compared to other species – may also play a role. With the development of bigger heads, rearing a human child became more energetically costly and therefore required greater parental investment. Concealed ovulation translates into uncertainty regarding fertile periods and therefore paternity. Under these constraints, the easier it is for the sperm to reach the egg, the easier it is to mate; a simplex uterus ameliorates these constraints.

Conclusion

A Darwinian approach to medicine helps elucidate risk factors, mechanisms, and treatments for disease and discomfort. Through an evolutionary lens, we were able to connect the modern issue of incessant ovulation to the evolution of concealed ovulation, menstruation, and invasive placentation, as they pertain to risk of ovarian cancer. Research should not neglect evolutionary origins as it explores modern disease.