The Politics of Seeing

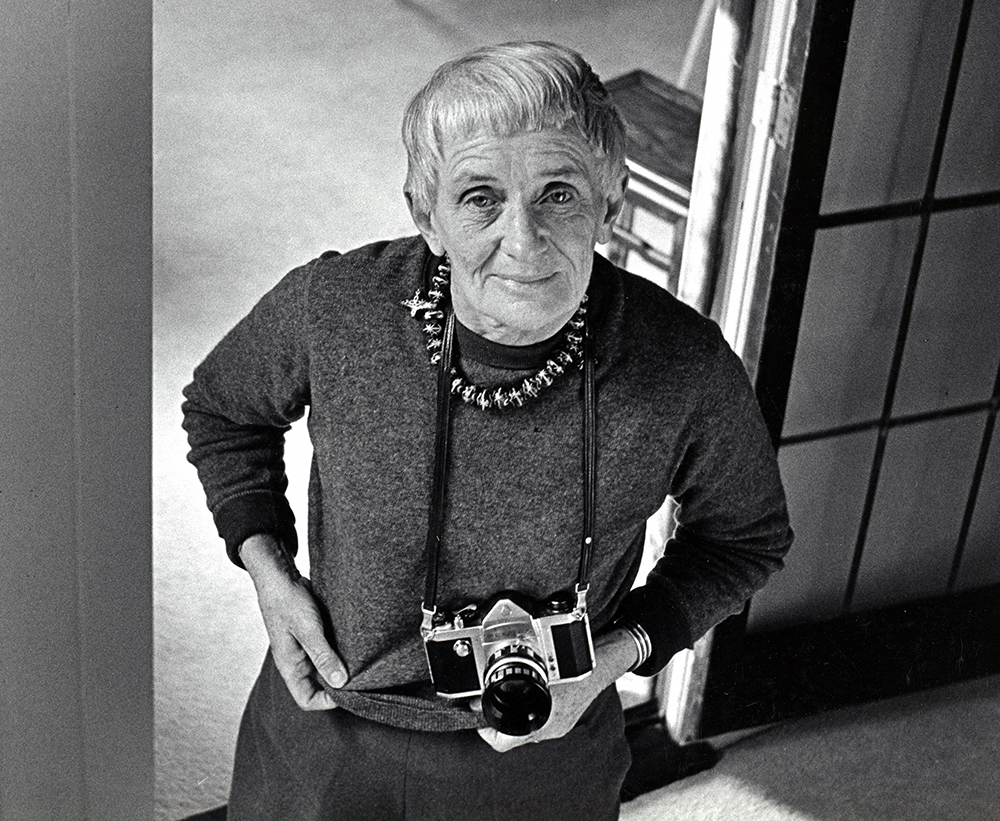

Hopefully summer time is going swimmingly for everyone, whether you’re in internships, jobs, or are relaxing. For museum-goers, popping into an exhibit or two (or thirty) during the dog days is a favorite past-time. And that’s exactly how I kicked off my summer, by visiting the Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeingexhibition in Nashville at the Frist Art Museum.

The difference from last summer to this one is that I have a year of museum studies under my belt, and now I am looking at exhibits with a critical (albeit, novice) eye. Here is my shameless plug and a challengeto anyone reading: send in an exhibit critique this summer for a guest spot on the blog. We would love to hear from places around Boston and beyond—for the nomads. I personally would love to read more about and experience more exhibits that show museums care about engaging all walks of life.

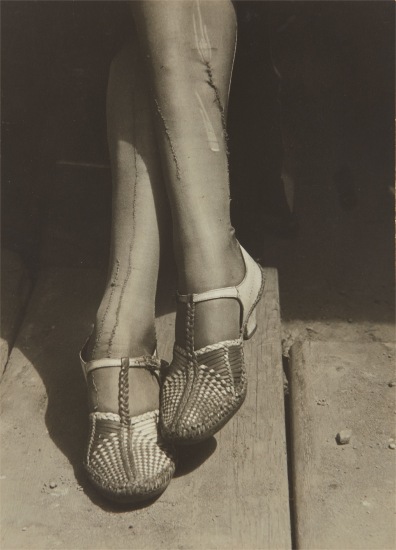

So, rewinding, Dorothea Lange… who is she? She’s a popular photographer from the 20thcentury who used her camera as a tool for justice. She wanted to expose inequalities in regard to race and gender, to address issues around the Great Depression and migrant workers, and to demonstrate the decline of the rural communities and environments. These topics are not unfamiliar to us today, if you will excuse the double negative.

I’ll be frank—I am not a photography fan. I can get down with a selfie or a scenic vista, but my world isn’t transformed by many pictures. I don’t know if it was my schooling coming in handy or maturation on my part, but I appreciated this exhibit for what it was trying to do, to give its audience a lesson on a compelling woman in history who visually captured the lives of those who would have been lost to time and to subtly make a point about how the world hasn’t changed in many ways.

Like many reinvented museum exhibitions today, this exhibit was clearly standing up for something. It wasn’t shying away from pointing out the injustices of this country. The major critique I would give is that it didn’t necessarily give an answer on how to change the oppression of minorities or the neglect of the poverty-stricken in this modern age. However, it does have a charming way of showing how photographs can be edited by the owner to represent the message the owner wants, rather than revealing the whole, complex truth.

We should care about that visitor connection for so many reasons, but I will start with a basic one: many people for centuries haven’t seen “their story” in a museum and that’s fortunately changing. This exhibit was giving a low down on some of the rundown minorities of the past, but it wasn’t as accessible as it could’ve been due to entrance fees. Go away from this article today thinking about how museums can become more connected with the unconventional museum goer. (On a personal note, feel free to drop a line about how to spice up photography exhibits.)