Teaching About Mental Illness at the Museum

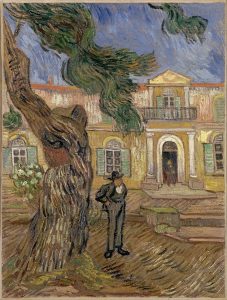

“It disgusted me even to move,” wrote an artist to his younger brother, “and nothing would have been so agreeable to me as never wake up again.” The year was 1889; the place, the Saint-Paul Asylum in Paris; the artist, Vincent van Gogh.

We’re accustomed to seeing Van Gogh’s breathtaking work in the museums we visit. Maybe, like me, you’ve marveled over a number of his paintings at the Norton Simon Museum in Los Angeles, far from his home in the Netherlands; or you’ve reflected on his self-portrait right here in Massachusetts at the Harvard Art Museums; or perhaps you’ve even gotten to step right into the artist’s world by experiencing the immersive Van Gogh Exhibition.

We know well how to appreciate his work. But have you ever seen a museum deal candidly and compassionately with his mental illness?

As someone who cares deeply about mental health advocacy, I often wonder how — as an emerging museum professional — I can do my part to educate our world on the realities of mental illness. Many people still carry harmful misconceptions about mental health, even as they appreciate the work of artists and public figures whose lives were marked by such unseen sicknesses. Although there are countless historical figures whose writings, work, and actions make clear that they would now be diagnosed with some type of mental illness, the museums dedicated to these people rarely ever acknowledge the profound difficulty that they faced in life as a result of this. As museums, bound in our responsibility to educate and enlighten the public, shouldn’t shedding a light on mental illness be part of our job?

As it turns out, some museums across the globe are doing just that. Holland’s Van Gogh Museum, in fact, dedicated an entire 2018-19 exhibition to its subject’s mental illness. Van Gogh Dreams plunged visitors into an immersive journey through Vincent’s dark time spent in Arles, France in the late 1880s, where he ultimately suffered a terrifying breakdown. In order to help visitors understand what the artist was going through, the museum recreated his experience with the help of “a dark room with flashing red lights and shattered mirrors.” By creating such a visceral experience, the Van Gogh Museum invited visitors right into the tortured mind of Vincent Van Gogh in some of his most difficult moments — and there is perhaps no better way to foster empathy.

Several former psychiatric hospitals function as museums today, shedding light on mental health history, telling the stories of the residents by displaying their artwork, chronicling the mistreatment they faced with surgical tools and equipment, and challenging visitors to overcome their own internal stigmas surrounding mental illness. (A few such museums are the Glore Psychiatric Museum in Missouri, the Oregon State Hospital Museum, and California’s Patton State Hospital Museum.)

In 2017, the Museum of Science in Boston did groundbreaking work by becoming likely the first major American museum to address mental health from a scientific standpoint — but the goal, MOS staff explained at the time, was not to flood visitors with statistics and information, but instead to make people who live with mental illness feel welcome and heard, and to inspire empathy in all others. This should be the aim of every museum tackling topics of mental health — which, I believe, should be most every museum.

Then there is the question of visiting museums while mentally ill. Museums are institutions for all, places where people can come and be refreshed and rejuvenated — places where we should all feel that we belong. Yet issues of accessibility mean that, for so many, museums don’t feel like an option. The article “The Unseen Museum Visitors: Persons With Mental Illness” encourages museums to reach out to local mental health professionals, collaborate and share resources with one another, and simply embrace the idea of truly creating a community for all people. By committing to greater accessibility, education, and compassion, museums can be part of the solution to the discrimination that people with mental illness experience all too often.

About 1 in 4 American adults suffer from a diagnosable mental illness. This means that, should museums decide not to tell the stories of or create welcoming environments for human beings with mental health struggles, nearly 58 million people in this country alone will be neglected. There is great power in the museum to foster welcoming for those who have felt unwelcome all their lives, and to teach empathy to all others.

Imagine how many people would feel represented if every museum that displays a Van Gogh recognized his mental illness with grace, compassion, and knowledge. He, and so many others, deserve to have their truth told.

Thank you for addressing an issue that so many live with, but it is still hush-hush.