The experience of a psychotherapist treating survivors of sexual violence in Tigray

This blog contribution describes the author’s discussions with Dr. Feven Tekelehaimanot, a Tigrayan psychotherapist who has been working with Tigrayan survivors of sexual violence perpetrated during the on-going war. The essay includes details of survivors’ accounts of violence that readers may find disturbing.

One day last month I met a young psychotherapist named Feven Tekelehaimanot. She is a lecturer at the medical school of Mekelle University, who has been involved in the treatment of women victims of sexual violence in Tigray. This experience brought her close to the horrendous suffering of the victims as a result of mass rape that can only be described as genocidal.

Feven has written a book, in Amharic (soon to be published), which is being translated into English. This blog post draws attention to her work and forthcoming publication.

In her six months of her assignment as a psychotherapist, Feven delivered her services to victims in twenty urban and rural locations including in Axum, Mahbere Diego, Daero Hafash, Eedaga Arbi, Semema, Eedaga Selus, Eedaga Berhe, Ahseaa, Rama, Feresemai, Gendebta, Yeha, Adwa, Enticho, Eedaga Arbi, Maikinetal, Chila, Ferima, Debregenet, and Debrebirhan. During those times, she treated over 331 women and girls. Her patients were of all ages. The oldest was a 75-year-old grandmother and the youngest was a child of six years.

Feven tells me:

The violence the women faced took many horrific forms: gang rape by members of a single force; gang rape by multiple forces; rape with foreign objects; abnormal sex; rape while other family members (including children, husbands and fathers) were forced to watch; rape while looking at the remains of deceased loved ones; and gang rape on mothers and children together. I learned that all the victims were raped along with dehumanizing insults and degrading names regarding their racial background and they themselves as persons.

I have facilitated medical assistance to those who had physical problems including: the interruption of rape-induced pregnancy; various forms of reproductive system infections; fistula; and bullet wounds. I have also treated my patients for various forms of psychological problems including: post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, all kinds of somatic symptoms, panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive disorders and attempted suicide being some of them.

I myself have passed through an agonizing experience while treating my patients.

Many victims died from the abuse. Many others are struggling to survive the trauma of the suffering they went through. I have cuddled and attempted to comfort many of those who are grieving for lost family members and are still suffering from the physical and psychological consequences of the violence they endured. I learned that the whole population of Tigray is struggling to survive the genocide but learned that those victims of sexual violence are the most challenged, devastated, and disadvantaged in their struggle.

Victims of sexual violence need resources and a complete support system that includes medical, legal, economic rehabilitation, and psychosocial rehabilitation support services in order for them to live from one day to the next.

Furthermore, Feven explains that access to such services is extremely limited in Tigray. She continued:

Rape victims have to travel to those centers, pay for their transport and their stay for treatment when and if the centers decide to treat them as outpatients. Some may not have immediate family members to assume nursing, child-care, and household responsibilities during their travels for treatment. Many of them do not even have the means to eat and have to work every day to get the necessities of life, which further impairs the likelihood that they will decide to access medical care. As a result, the rehabilitation of rape victims is not possible without meaningful economic support.

I believe that the return of rape victims to a dignified life is not possible without administering formal and proper reparation. By reparation, I include the restoration of circumstances that existed prior to the violence (restitution) and compensation for resulting material losses, as well as physical and emotional pain and suffering; legal, medical and psychological assistance to assist their rehabilitation. As well as restorative measures, I foresee that justice in Tigray should include criminal accountability for murder, sexual violence, and other crimes.

Ethiopia is party to international treaties that oblige it to ensure that victims of human rights violations, including rape survivors, have access to an effective remedy, including compensation, and to the highest attainable standard of health. Nevertheless, Feven knows that Ethiopia has never had the capacity to meet its obligations in implementing the international treaties it signed and ratified. Tigray is going to face a huge task of creating an enabling environment for dealing with rape crimes according to the international treaties ratified by Ethiopia. The task of addressing the medical, psychosocial, economic, and legal needs of the victims of the genocide will in any case fall on the shoulders of Tigray and its government. It is therefore mandatory for Tigray to create the infrastructure capable of dealing with a huge caseload. The regional government of Tigray also needs to review and update its legal measures to introduce measures to respond to the problem of sexual violence of all kinds, not just conflict-related or genocidal rape.

Feven insists:

The international community failed to intervene to stop the genocidal war in Tigray. For this reason, the international community has a responsibility of addressing the consequences of its failures. This includes funding projects to enhance medical and psychosocial care and other assistance to survivors, including victims of sexual violence, whose persistent and worsening economic and health difficulties place them among the most disadvantaged of genocide victims.

While thinking of the current and future challenges of Tigray, Feven has been thinking of a role for herself. She says,

My experience has exposed me to the challenges of the psychosocial rehabilitation of the victims of genocidal rape. My experience can be used in planning the future rehabilitation efforts of similar victims.

I also believe that the stories of the victims should be told publicly so that the depth of the problem and the challenges of dealing with them can be more fully understood.

For this reason I have written about the identification and treatment of rape-induced mental problems drawing upon the cases I have treated.

Feven gave me the privilege of reading the manuscript of her book. It is both deeply moving and full of important insight and lessons for policy and practice. After summarizing the lessons learned in treating similar patients, she details the multi-faceted aspects of the crimes of genocidal rape in Tigray; the manifestation of the mental problems it induced; and the challenges of treating them.

In the second part of her manuscript, Feven tells the stories of sixty rape victims. Though painful and challenging to read, this section helps people understand the gravity of the crime and the challenges of dealing with the problems.

Feven is also developing a project for developing an institution to treat victims of sexual violence in general and those victims of the genocidal violence in particular. The project considers for the medico-legal training of health workers; legal review (be it at national or customary law level); the provision of health extension services of psychotherapy to victims of the genocidal war. Her idea is to call for partners — private individuals, organizations, and public institutions — to champion these ideas and ideals.

Faven’s work showed me that there is a spark in the middle of darkness given that all stakeholders understand the magnitude of the problem and join hands towards addressing it. I wish anyone interested in joining hands with Feven contacts her.

Below, I am reproducing one of Feven’s many testimonies randomly picked from the sixty stories in her book and will publish more details about her research and project, leading up to the launch of her book.

You made Mama bleed! You won’t touch her again!

February 13, 2021

Mihret[1] is 27 years old, married, and a mother of two. She used to live in Shiraro town, North-western Tigrai. Her kids are a four year old son and an 18 month old daughter. Mihret was originally butt-raped by a group of Eritrean Defense Force (EDF) soldiers (a.k.a. Shaebia soldiers) while she was piggybacking her daughter and her son was forced to watch. After a brief moment and more humiliation, she was again gang raped by the same EDF soldiers and left broken in the middle of an abandoned village. She later manage to reach into an IDP camp in one of the towns in central and north-west zones of Tigrai. I found and treated her in the IDP camp she was sheltering. I was told that she repeatedly attempted suicide.

She narrates the horrendous crime inflicted upon her in the following way.

The joint EDF and ENDF forces, who approached the city from the north-west and west of the city respectively, were shelling the town and people were fleeing out of the town in any direction they felt safe. I was alone as my husband had travelled away during that time and decided to stay with my parents who lived in a place called Tsedia (Central Tigrai). But the time of my departure was late and I was caught by three EDF soldiers at the outskirts of Shiraro.

Upon seeing me with my children, the soldiers asked me to stop and began asking me questions like: who are you? Where from are you coming? Where are you going? Etc.

I answered to all the questions they asked genuinely. I told them my name: told them that my husband had travelled for business; and also informed them that I was fleeing the war to join my parents at Tsedia for the safety of myself and my children.

They listened to my answers but told me to go by a house nearby and stand outside facing the wall as they were going to search me. I did exactly what they told me to do. I did exactly like they asked while piggybacking my daughter and my four year old son remained with them. Then two of the soldiers in the name of searching me started touching me inappropriately.

I kept quiet.

The one started touching my breasts and the other started rubbing my genital area.

I started crying.

The third soldier came from my back and began uncovering my dress from behind to which I reacted by trying to pull down my dress and cover back. Then the soldier hit me hard and asked me to stop trying to cover and stop crying.

He shouted at me to shut up to which I did but heard my son crying from behind. It was painful. Knowing of the shameful thing they were going to do on me, I avoided to see the face of my son and failed to comfort him.

The soldier who was behind me shouted to my son to come closer to him pulling him by his ear. I immediately turned my face and begged him to leave my son alone! To let him play! And do whatever he wanted to do with me.

But the soldier continued to hold my son crying and shouting without giving any attention to my pleas. He then ordered me to turn and face the wall again and continued to uncover my dress from behind leaving my ass bare on the air.

I couldn’t comprehend what was happening!

The soldier butt-raped me while I was piggybacking my daughter. My son was forced to watch and he was crying out loud. He was thrashing around crying. The second soldier replaced the first one once he has had enough and the second one continued to do the same thing, and then the third one continued and my butt began bleeding.

It was my son who saw me bleeding first. He used all the power he had and cried loud saying: “Leave her alone! You made my mom bleed!”

The third soldier didn’t realize that I was bleeding up until he heard my son demanding him to stop making me bleed. After listening to my son, he saw the bleeding, and pulled out his genitals insulting me all kinds of insults. He then did hit me hard out of disgust. Seeing him disgusted was another shock to me. I asked myself: How is it that he is not disgusted of himself and I am considered responsible for my bleeding?

It was then that I pulled down my dress and covered by back. The blood dripping from my butt began soiling my dress with blood. My son then came to me, grabbed my legs from my back and kept shedding his tears.

He then started shouting “…Mama, Blood! You bled! You are bleeding Mama!” I still hear him saying that in my ears every single day! I asked him to come forward tried to comfort him and hugged him tight.

The two soldiers then insulted and snatched him from me and threw him in the ground. My daughter was on my back and crying and both soldiers turn by turn raped me through vaginal sex. This were the ones who few minutes ago ass-raped me and handed me to their third colleague who threw me with disgust when he saw my butt bleeding. I couldn’t understand how their bodies made themselves ready for a second round of sex in such circumstances. They then left me lying on the ground with my children.

I then dragged myself into one of the looted and broken houses and prostrated. My daughter was continuously crying but there was little I could do to her. My son went searching for something to eat. He brought Injera with salt. He tried to feed me where I laid down. I couldn’t eat. I hated everything.

My son then asked me “Why Mama? Are you sick?”

And I replied “Yes! Just a little! I’ll get better if I sleep! Let me sleep ok?’

My son with his little mind did everything to comfort me. He said: “Don’t worry Mama! I’ll not spare the lives of the ones who caused you this pain! They will never hurt you again! Okay Mama? I will kill them for you!”

Shedding my tears I said ‘OK’.

My son keeps continued repeatedly saying ‘I will not leave them!’ Tired of the pain and humiliation I felt I soon fell asleep.

Mihret was continuously crying while she was narrating the story of her pain to me. She felt tired and said ‘Huuuuuuh!’

While listening to her story I was quietly listening to her and struggling with myself to control my emotions. When I saw her taking a break, I simply told her how heartbreaking it is and how sorry I am.

‘Feven!’ Mihret said after a brief break. ‘My sad and heartbreaking story didn’t end there. What happened after a couple of days was my most devastating experience.’

After resting for few days in the nearby village I felt better and decided to continue to continue to walk to my father’s place. I asked for the information about the places of deployment of the EDF and ENDF soldiers, identified the opening I could escape their trap and hit the road with my kids. To my relief, I saw members of the Tigrai Defense Forces (TDF) members coming in a row after a long walk for the day.

I was so excited. I told to myself ‘cheer up! This atrocity and suffering will end one day! And ululated loud.

However, my son was a bit confused, he crossed the street and picked a huge stone to hit the TDF members that were approaching to greet us.

I was shocked.

I said to him ‘These fighters are ours! They are not the bad ones!

While I was exchanging these words with my son all the TDF soldiers stopped where they were and took a break. One of the TDF members came forward from his row and held my son’s hand and began talking to him.

He asked him: “What’s wrong little one? What’s the matter?”

My son was crying while still holding the stone in his hand and said to him: “You are the one who made my Mama bleed! It is you! You won’t touch her again!” and continued to get his hand released from the man holding him.

The TDF guy couldn’t understand what my son was saying and got confused.

He asked me different questions consecutively. I couldn’t answer them. I grabbed and hugged my son so tight and kept crying. I was touched. The TDF soldier went to his commander and other members of the force and told them about the situation.

The commander ordered “let’s all take five minutes break!” Only a few who were selected came back to us and started to wait to hear about it.”

The commander said that they have never faced such a thing. He further stated that children cheer them up and greet them happily chanting and singing and stated that he was confused with the reaction of my son asking me to explain for him if I can.

I then told him that the problem was not with them but with those uniformed soldiers who tortured, raped, and humiliated us. I told them what the EDF soldiers did to me few days ago. I told them how my son was forced to watch me being raped to bleeding. I then told them how my son has pictured our enemies. I finally told them that seeing them in some form of uniform made him mistake them for the enemies who attacked us and he meant to protect his mom from a similar attack.

The TDF soldiers felt sorry, some even cried with us. They told us that they are fighting so that these atrocities could end and assured us that this will end shortly. They then indicated us the safest direction to the nearest town where there is an IDP camp and we departed.

Hearing her story was extremely painful. I discussed with her about how traumatic experience led people to generalize events. Her son, so young and traumatized of the experience he witnessed can only see anyone with uniform and armed as someone who rapes and makes his mama bleed. I added that this is just the first stage and I will be working with her so that we jointly help her son pass this stage of generalization.

It was after this that I asked her about her attempt for suicide at the IDP center.

She again began crying deeply and said:

Believe me Feven! I want to live for the sake of my children! Believe me! I want to!

But, thinking of the disgrace I faced, thinking of the butt-raping, knowing that my son has seen it all, I just couldn’t breathe! My will to live for the sake of my children was defeated and I tried to kill myself by taking as much pills as I got at one time.

Slowly she began telling me on the detail symptoms of her trauma. She detailed out that she is always sad after the assault and depressed all the time. She said that she has never felt happy since that sad day:

How can I be happy again? What happened to me has never happened to others, can you imagine that it was in front of my son? How can I be happy again? I am a woman cursed for sadness.

I assured her that she is not alone! It is nothing of her fault. I told her that it is not her but those criminals who inflicted the crime on her that should be ashamed and humiliated. I promised her that I can facilitate the interruption of her pregnancy and advised her not to hurt herself. I also promised her that I will work together with her to maintain the physical and psychological health of her kids.

I told her of the steps we will follow to deal with her physical and psychological problems and began a long journey with this young lady. The first step will be addressing the physical medical problems (checking pregnancy and interrupting it when and if she desires and it is medically feasible; checking her for STDs and taking her through the necessary steps for treatment and beginning the treatment when and if there is a problem and so on). Then will follow step-by-step therapeutic sessions. The key aims for the therapeutic sessions are to help her out any sense of guilt and to assist her move forward in the direction of doing what is possible. Our effort to support her economically was limited to virtually nothing as the supplies available were limited due to access problems and restrictions.

[1] Her name has been changed.

Mulugeta Gebrehiwot was a Senior Fellow at World Peace Foundation and former Program Director of the WPF African security sector and peace operations program where he led the project on Peace Missions in Africa.

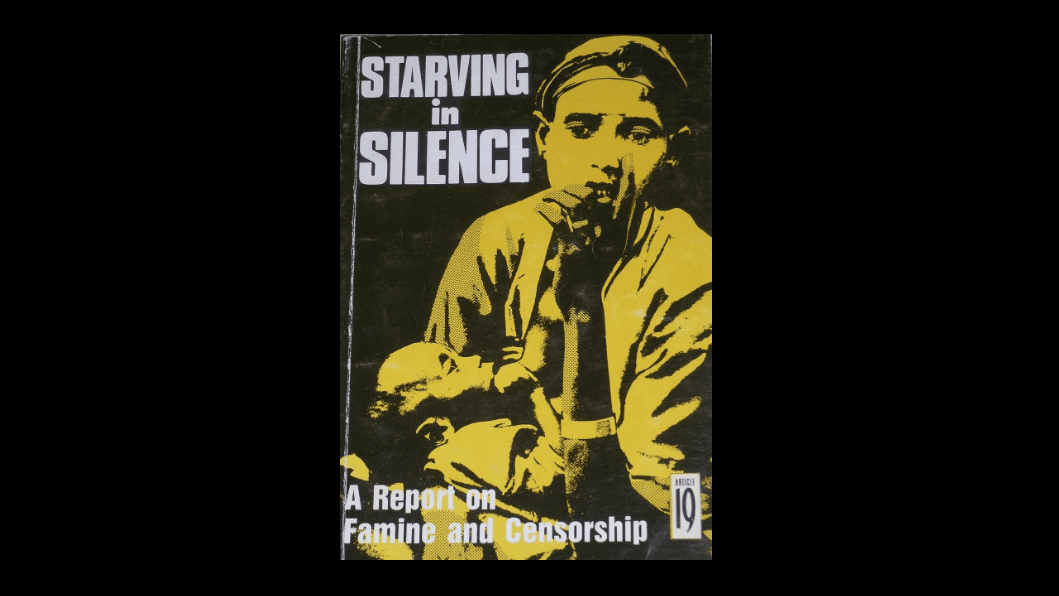

Image: Tigray Visit, UNICEF Ethiopia/2020/Mulugeta Ayene