My Sites

Log in to create or edit your sites.

IMPORTANT SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT: Content freeze 7am June 19th until 7am June 23rd. Read more here.

Need Help? Email edtech@tufts.edu

Site-Wide Activity

-

Thomas Quinn wrote a new post on the site What's New @ HHSL 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Tegan Kehoe wrote a new post on the site Museum Studies Blog at Tufts University 10 years, 7 months ago

The Visitor Studies Association (VSA) is looking ahead to its July 2016 conference in Boston and sending a special invitation to area Museum Studies students to get involved in the association. Marta Byer of the […]

-

Marcy Regalado wrote a new post on the site X. 10 years, 7 months ago

Last evening I had the pleasure of joining alum Captain Rick Hauk, A’62. Now I personally always get so gitty when meeting an alum as it’s the chance to speak with someone who has gone through a different Tufts, […]

-

Kourosh Asha is attending Seminar IV. 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Saloni Angra is attending Seminar II. 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Brooke Traylor wrote a new post on the site Museum Studies Blog at Tufts University 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Robert L. Franklin is attending Seminar III. 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Jeneice Collins wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

Emotion Regulation in Schizophrenia

Emotion Regulation in Schizophrenia(http://www.psycholawlogy.com/2014/05/26/emotional-intelligence-emotion-regulation-ability-helps-lawyers-interact-others-effectively/)

Schizophrenia is associated with […]

-

willie wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Jeffrey Aalberg wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

In the previous blog posts, Deep Brain Stimulation was introduced, then the history of psychosurgery leading up to the treatment of depression was traced. In this post, we will cover some of the neurological theories as to why it is an effective treatment. We will begin with the prevailing theories behind the treatment of depression with DBS, then move on to explore some more novel ideas.

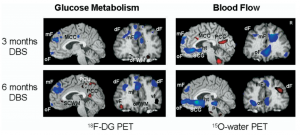

This images shows changes in oxygen and other metabolic usage in different areas of the brain following chronic DBS treatment

The most commonly targeted area of the brain in DBS for depression is the Subcallosal Cingulate Gyrus (SCG), which has been known to be heavily involved in mood regulation. Early studies showed that both successful pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy lead to reductions of activity in this area. Lozano et al (2008) furthered these studies by showing decreases in activity in the orbital and medial prefrontal cortices and insula, as well as increases in the parietal lobe, mid and posterior cingulate gyri. Most importantly, their study showed increases of activity in white matter immediately next to the electrodes. The discovery of a wide range of affected locations, as well as the activity in connective tracts, became a key step in establishing the treatment of depression as the treatment of a network.

The idea of neural connectivity has become a favorite in exploring depression. Johansen-Berg et al. (2008) did a tractography analysis to see how different areas of the brain are connected. The subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sACC) was closely examined as it was predicted be a hub of the depression network. They determined that DBS targeting the subgenual portion is effective in part because it affects the OFC, hypothalamus and amygdala. These results in part replicated Lozano’s work and solidly established the detailed study of networks in depression. The role of the sACC as a neural hub is also supported by Sjoberg and Blomstedt (2011) who use it in an attempt to wed two older ideas on depression, the Catecholamine Hypothesis and the Vicious Cycle Theory, by finding a single nucleus of common ground.

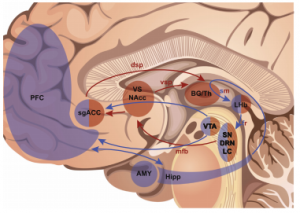

This image shows the dual-loop system. Regions in brown are the fast inner loop, and blue regions are part of the slower outer loop. (Hoyer et al., 2013)

Despite the success of pinpointing neural locations, the problem of explaining both the acute and delayed effects of DBS was still a loose end. Hoyer et al. (2013) addressed this question by dividing the known neural circuitry in two. The first loop is described as the inner, or fast-acting, loop. This includes the thalamus, striatum and sgACC. This loop is predicted to be responsible for the acute effects that can manifest themselves while the surgery is in progress. However, they admit that this discovery is complicated as the surgical procedure can cause microlesions of the site, which may lead to similar effects.. Their outer loop connects cortical areas of the front lobe, the amygdala and hippocampus. They advance the notion that neuroplasticity in these areas contributes to restoring non-depressive behavior.

A new study has delved further into the effects DBS has on neuroplasticity and affect by looking at serotonergic neurons in mice. Veerakumar et al. (2014) experimented with DBS in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex, which has analogous function as the SCG in humans. The mice were defeated socially, they effectively got beaten up by older mice, which is a stressor that introduces depressive-like symptoms. They conclude that mice exposed to this social-defeat paradigm show an increase in length and number of dendrites of serotonergic neurons as well as desensitization. Veerakumar terms this as “maladaptive neuroplasticity.” His research then continued to show that DBS can reverse these effects as well as reintroducing normal social behavior. While this study does serve as a proof of concept, it does not explain yet another loose end; why do symptoms return so rapidly when the DBS electrodes are turned off?

This question among many others still needs to be answered. However, the efficacy of DBS became clear long before neurological theory could explain it. So, many of the studies here are not only working to improve its therapeutic capabilities, but also to figure out why it works. In the final blog post, we will look at the ethics of using what we have seen to be a largely unexplained and experimental treatment.

Works Cited:

Hoyer, C., Sartorius, A., Lecourtier, L., Kiening, K., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., & Gass, P. (2013). One ring to rule them all? – Temporospatial specificity of deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Medical Hypotheses, 611-618. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

Johansen-Berg, H., Gutman, D., Behrens, T., Matthews, P., Rushworth, M., Katz, E., … Mayberg, H. (2008). Anatomical Connectivity of the Subgenual Cingulate Region Targeted with Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Cerebral Cortex, 1374-1383. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

Lozano, A., Mayberg, H., Giacobbe, P., Hamani, C., Craddock, R., & Kennedy, S. (2008). Subcallosal Cingulate Gyrus Deep Brain Stimulation For Treatment-Resistant Depression.Biological Psychiatry, 64, 461-467. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

Sjöberg, R., & Blomstedt, P. (2011). The psychological neuroscience of depression: Implications for understanding effects of deep brain stimulation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 52, 411-419. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

Veerakumar, A., Challis, C., Gupta, P., Da, J., Upadhyay, A., Beck, S., & Berton, O. (2014). Antidepressant-like Effects of Cortical Deep Brain Stimulation Coincide With Pro-neuroplastic Adaptations of Serotonin Systems. Biological Psychiatry, 76, 203-212. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

-

Jennifer M. Perry wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

Welcome back!

To begin with a brief recap, the themes I have presented thus far under my topic of “Failures of Empathy” have ranged from the goals that drive ordinary individuals to attenuate empathic concern towards others, to the empathic deficits (both neural and psychological) that ultimately define certain abnormal behaviors. Today, I will be returning to a context that *unfortunately* seems to ubiquitously drive people to demonstrate failures of empathy: intergroup contexts.

The concept of ‘intergroup’ can be parsed into two terms: ‘ingroup’ and ‘outgroup’. These terms refer to numerous examples of group memberships, in which an ‘ingroup’ is a group to which an individual belongs, and an ‘outgroup’ is a group to which the individual does not belong. These can range from relatively socially-constructed groups, such as sports teams or sororities, to more cultural and stable factions, such as ethnic or religious groups. Often occurring in intergroup contexts are processes known as ‘ingroup favoritism’ (preferring one’s ingroup) and ‘outgroup derogation’ (disfavoring one’s outgroup).

Most of the research on failures of empathy in intergroup contexts has focused on racial ingroups and outgroup— and for good reason. There is something particularly potent about the social category of ‘race’ that especially drives us to favor our ingroup and derogate our outgroups. The large, and robustly demonstrated, discrepancy between empathic concern for our ingroups vs. outgroups has received so much attention in the literature as of late that it recently was termed the ‘intergroup empathy gap.’

Before neuroscientific methods were common in social psychology, a clever study by Johnson et al. (2002) demonstrated how failures of empathy within a racial intergroup context can result in very real-world implications. In this study, White participants acted as jury members in a mock trial for either a Black or a White defendant accused of the exact same crime. When the defendant was Black, versus White, the participants reported feeling less empathy for the defendant, made more attributional rationales about the defendant’s wrongdoing (assumed the crime was committed due to the personality of the defendant, rather than the characteristics of the situation), and ultimately assigned harsher punishments. Remember: the mock White and Black defendants were accused of the same exact crime.

A few years later, social and affective neuroscience researchers began to examine the neural bases behind this phenomenon. The first of these studies by Xu et al. (2009) explored how viewing ingroup vs. outgroup members in pain would differentially activate empathic concern. They showed White and Chinese participants photographs of both White and Chinese individuals in painful and non-painful contexts. Thus, all participants (whether White or Chinese) viewed members of both their racial ingroup and their racial outgroup in typical empathy-inducing situations. Results showed that a neural region typically involved in empathy, the anterior cingulate cortex, was far more activated when participants viewed ingroup vs. outgroup members in pain.

Perhaps, however, the effect demonstrated in this Xu et al. (2009) study was simply due to factors related to unfamiliarity. That is, because members of your racial outgroup are likely perceived a less similar to you, it may simply be more difficult to activate empathic concern for dissimilar others. A study conducted by Avenanti et al. (2010) addressed this possibility. They utilized a similar paradigm as Xu et al. (2009), showing Black and White participants photographs of Black and White individuals in pain. They added, however, a third set of photographs: individuals with violet–colored skin tone in pain (see below). If racial outgroup members represent relatively unfamiliar/dissimilar targets, the violet-colored individuals should denote entirely unfamiliar/dissimilar targets. Using transcranial magnetic stimulation, researchers examined the degree to which target pain activated sensorimotor reactivity—or the degree to which people experienced the targets’ pain as though they were experiencing the pain themselves. Astoundingly, results demonstrated that both Black and White participants exhibited neural empathic reactivity when viewing the pain of both their ingroup members AND the unfamiliar violet- group members. No such reactivity was evident when viewing racial outgroup members in pain. Thus, the unfamiliarity account does not seem to sufficiently explain the intergroup empathy gap.

So why does all of this matter? So what if a tiny region in a person’s brain activates less in response to some people over for others? Above, I mentioned one study that demonstrated how the intergroup empathy gap could potentially have negative real-world implications. Regrettably, one does not need to search long and hard for examples of this in our lives today. Following the recent shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri, a typical pattern emerged in the media. Justifications akin to victim-blaming were released in the days following the incident, ranging from speculation about his drug-use, to the possibility that he stolen cigarettes just prior to his murder. One fact ironically remained clear during these media updates: Michael Brown was unarmed.

In the midst of this shooting, people on social media began to expose an even more disturbing pattern evident in the mainstream media: more favorable treatment of White murders than for Black victims. Like in the example below, White murders are ironically often depicted

as victims, and Black victims as bullies. See this link for copious examples of the treatment of Black victims vs. White murders in the media. In my opinion, this is the ultimate display of ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation via the intergroup empathy gap.

as victims, and Black victims as bullies. See this link for copious examples of the treatment of Black victims vs. White murders in the media. In my opinion, this is the ultimate display of ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation via the intergroup empathy gap.

In this post, I have described how both neuroscientific and psychological evidence demonstrate how people tend to experience less empathic concern for members of their outgroups versus members of their ingroups. While the extant literature on this topic is ample, there still remain several important questions. We now know that this happens… but why? My own work seeks to understand the specific mechanisms behind this discrepancy. Does decreased empathic concern towards outgroup members occur automatically, or is it the product of certain regulatory strategies? In the case of the Michael Brown shooting, did the public effortlessly feel less empathic concern for this black murder victim, or did they work to prevent any activated empathy from becoming compelling? If so, were the justifications made about his murder one means of regulating any existing empathic concern? Stay tuned (well, for years to come) for some answers— hopefully!——————————–

Avenanti, A., Sirigu, A., and Aglioti, S. M. (2010). Racial bias reduces empathic sensorimotor resonance with other-race pain. Current Biology, 20, 1018–1022.

Johnson, J.D., Simmons, C.H., Jordan, A., McLean, L., Taddei, J., Thomas, D., et al. (2002). Rodney King and O.J. Revisited: The Impact of Race and Defendant Empathy Induction on Judicial Decisions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(6), 1208-1223.

Xu X, Zuo X, Wang X, Han S. (2009). Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 8525-8529.

[Photo of Media Treatment]. Retrieved November 18, 2014 from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08/14/media-black-victims_n_5673291.html

-

Irina Yakubovskaya wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

In this blog as a whole, I have been exploring the ways that Theatre and Affective Neuroscience might be in fact each other’s reflections, since both work closely with emotions. Both theatre (acting in particular) […]

-

Below is some additional more detailed information about the neural processes of emotional prosody… I didn’t feel like it had a place in this blog post, but it’s very interesting:

Adolphs and colleagues (2006) suggest that early and later perceptual processing of the auditory features of a stimulus involve primary and high level auditory cortices; the amygdala and the oPFC link the perceptual auditory representations to structures that can enact emotional responses or that can reconstruct associated knowledge; motor and premotor structures play a role in simulating components of the emotional body state normally associated with producing the emotion (the right premotor cortices, left frontal operculum, and the basal ganglia); and finally, somatosensory structures in the right hemisphere represent the emotional body states simulated by the motor structures.

Wildgruber suggests a three-step process to describe the perception of emotional prosody:

The first step, extraction of supra-segmental acoustic information, is associated with activation of predominantly right hemispheric primary and secondary acoustic regions. The second step, representation of meaningful supra-segmental acoustic sequences, is linked to posterior aspects of the right superior temporal sulcus. The third step, emotional judgment, is linked to the bilateral inferior-frontal cortex (IFC). (p. 278) -

And for those who are interested in empathy, here is a research that links it with gibberish language:

Besides being an essential component of human social and emotional development, gibberish is linked to empathy. In 1995, Ellen Junn and colleagues conducted an experiment where 61 young college students were asked to interact fully in gibberish (a minimal script and some directions were provided). The topic of their conversations was “Multicultural awareness.” As a result, the majority of students admitted that after participating in the exercise, they felt “more sensitized, appreciative, and empathic to the challenges that face nonnative English speaking students.”

Junn, E. N., Morton, K. R., & Yee, I. (1995). The” Gibberish” exercise: Facilitating empathetic multicultural awareness. Journal of Instructional Psychology.

-

I just want to add from a computational perspective the importance of prosody in understanding emotions. Most computational speech recognizers of emotions take advantage of various prosodic cues, and the effectiveness of using just prosody is far greater than most models that use the semantics of what is being spoken. However, this becomes problematic if the speech lacks prosody. My lab is currently working on a project with Parkinson’s patients. One symptom they have is a significant lack of prosody in their speech. This makes it difficult for people (never mind computers) to assess the affective content of what is being said.

-

-

Victoria A. Floerke wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

Well, by now enough time has past since my last post that I’ve binge-watched my way through most of Gilmore Girls. I always lose interest after season five; the show (sadly) jumps the shark shortly thereafter. Fortunately, there are plenty of other shows that also jump the shark to choose from. Since I was already watching characters who wanted to feel good feel badly anyway, I figured I might as well up the ante and revisit Homeland, a thriller that centers on a brilliant CIA agent, Carrie Mathison, suffering from Bipolar I Disorder. After all, wanting to feel good can sometimes be worse than upsetting for some people; it can even sometimes be clinically incapacitating.

How Are Positive Emotions Bad When You’re Really Up?

Although experiencing positive emotions 24/7 may seem cool, most people affected by bipolar disorder would probably beg to differ. It certainly debilitates Carrie; her job and her life are constantly on the line, in no small part because she takes risks no one else at the CIA will. Now, as much as I enjoy Homeland, I will say that Carrie’s presentation of bipolar disorder isn’t exactly consistent with the explicit criteria set forth by the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Roughly, though, Homeland is correct in portraying the manic states that typify the first part of bipolar disorder as being characterized by racing thoughts, grandiosity, decreased sleepiness, excessive talkativeness, risk taking, distractibility, and, in Carrie’s case, increased work productivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

It’s a good thing she *spoiler alert* gets promoted later… (Image retrieved from http://pixel.nymag.com/imgs/daily/vulture/2011/ 12/12/12_homeland.o.jpg/a_560x375.jpg)

It’s hard not to get tripped up on the idea that people undergoing a manic episode can experience increased work productivity. Corporate America usually rewards this kind of output, doesn’t it? But mania clouds decision-making. Research suggests that while people at risk for experiencing mania, like Carrie, indeed experience greater positive emotion, they also experience increased irritability and have higher cardiac vagal tone, an index of positive emotionality, when watching positive, negative, and neutral film clips (Gruber et al., 2008). Being so hypersensitive to positive emotion that you can’t differentiate between, say, happy and sad film clips can’t bode well for decision-making. Relatedly, people with bipolar disorder and a history of psychosis seem less able to objectively revisit positive emotional experiences than other people. In other words, despite having memories that are objectively as positive as participants with bipolar disorder without a history of psychosis and healthy controls, they have greater emotional responses to these recalled memories. They likewise exhibit stronger left frontal activation, an index of positive emotional reactivity, during positive emotional event recollection (Park et al., 2014). Thus, although experiencing near-constant positive emotionality isn’t preventing people like Carrie from more or less living their daily lives, they are influencing how they perceive the world in consequential ways.

How Are Positive Emotions Bad When You’re Really Down?

Unquestionably, the excessive positive emotionality that typifies mania is bad in and of itself. Yet it’s the second main part of bipolar disorder, the major depressive episode (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), that arguably most upends people’s lives. We already learned that people who really want to be happy paradoxically feel less happy than people who don’t really want to be happy. As it turns out, though, unhappiness isn’t the only unfortunate outcome of really wanting to feel happy; on the contrary, valuing happiness is also associated with depressive symptoms. Moreover, the more one values happiness, the more likely one is to have been diagnosed with depression (Ford et al., in press). Though Carrie’s mania makes her want to feel more positive emotions, she can’t sustain such a state; consequently, she eventually spirals into a depressive state so severe she’s hospitalized.

While Homeland provides an interesting framework for considering the role of positive emotion in psychopathology, this relationship isn’t just limited to manic and depressive episodes in bipolar disorder. For example, one study has suggested that survivors of childhood sexual abuse do not have good downstream social outcomes if they express positive emotion while describing past abusive experiences. Survivors do, however, seemingly have good downstream social outcomes if they express positive emotion while describing past events not related to their abuse (Bonanno et al., 2007). This suggests that the context in which positive emotions are expressed can still have varied effects, even within broader realms of psychopathology.

So, you might be wondering to yourself, if positive emotions can cause psychopathology, can we use positive emotions to make people suffering from psychopathology feel less negatively? Well, yes. Techniques like mindfulness meditation may increase levels of vasopressin and beta-endorphin, as well as increase activation in the left anterior prefrontal cortex, the lateral hypothalamus, and the median forebrain bundle, all of which may lead to increased positive feelings and serotonin release useful in treating depression (Garland et al., 2010). It’s too soon to say, but targeting positive emotions may even eventually be useful when treating people like Carrie, so long as they don’t end up swinging too far back to the positive side.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Today you hopefully learned that excessive positive emotion plays a role in psychopathology, particularly in Bipolar I disorder and Major Depressive Disorder. They implicate frontal processes that may make people suffering from Bipolar I disorder more sensitive to positive emotions, but they may also be helpful in activating frontal processes that aid in reframing emotional events in more positive lights during treatment for depressive episodes. Carrie’s dramatized experience of bipolar disorder, for all its flaws, is to my mind relatable to Americans who suffer from the psychopathology. What remains to be seen, however, is whether people from other parts of the world feel the same way. Do they even want to experience positive emotions the way Westerners do? We’ll discuss important cultural differences in positive emotion valuation and experience next time.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.

Bonanno, G. A., Colak, D. M., Keltner, D., Shiota, M. N., Papa, A., Noll, J. G., … & Trickett, P. K. (2007). Context matters: The benefits and costs of expressing positive emotion among survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Emotion, 7(4), 824.

Ford, B. Q., Shallcross, A. J., Mauss, I. B., Floerke, V. A., & Gruber, J. (in press). Valuing happiness is associated with symptoms and diagnosis of depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology.

Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L.(2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 849-864.

Gordon, H. & Gansa, A. (Executive Producers). (2011). Homeland [Television series]. New York: Showtime Networks.

Gruber, J., Johnson, S. L., Oveis, C, & Keltner, D. (2008). Risk for mania and positive emotional responding: Too much of a good thing? Emotion, 8(1), 23-33.

Park, J., Ayduk, O., O’Donnell, L., Chun, J., Gruber, J., Kamali, M., McInnis, M., Deldin, P., & Kross, E. (2014). Regulating the high: Cognitive and neural processes underlying positive emotion regulation in bipolar I disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 1-14.

Sherman-Palladino, A. (Executive Producer). (2000). Gilmore girls [Television series]. Burbank: The WB Television Network.

-

Joshua Manning wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Kate Dahlgren wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Aleksandra Kaszowska wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Gizem Altheimer wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

In my second blog post, I introduced the concept of threat-relevant cognitive biases in people with social anxiety disorder (SAD). To provide a quick overview, below are some of the basic characteristics of attentional biases in general. Because threatening facial expressions are most relevant in the study of SAD, I will focus my examples here (and the remainder of my blog post) on this specific type of attentional bias. According to Cisler and Koster (2010), some observable characteristics of attentional biases are:

Facilitated attention to threat stimuli, meaning that those with SAD detect threatening faces faster than non-threatening faces,

Difficulty in disengagement from threat stimuli, meaning that those with SAD have a harder time disengaging their attention from threatening faces compared to non-threatening faces, and

Attentional avoidance of threat stimuli, meaning that those with SAD allocate their attention to things other than the threatening faces.As I demonstrated in my previous post, by now, there is a wealth of research that demonstrates that attentional biases toward threat exist in SAD; however the mechanisms comprising the biases remain unclear. So we know that it happens, and we know that on a neural basis, people with SAD differ from healthy controls in this respect, but we don’t yet know exactly why.

In an attempt to uncover one of the many underlying mechanisms of increased brain activity in response to threatening faces, Burklund, Eisenberger, and Lieberman (2007) showed brief video clips of facial expressions depicting disapproval, anger, and disgust to people who were either high or low on rejection sensitivity (note that these were healthy participants). The specific facial expression they were interested in was that of disapproval, which they explained is an indication of negative evaluation – “a signal that the target has done or said something socially undesirable and, consequently, has potentially damaged a social connection” (p. 239) – a concept highly relevant to SAD. They collected fMRI data from participants as they viewed these expressions. Their results indicated that individuals high in rejection sensitivity exhibited greater dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) activity in response to watching the disapproving video clip than those with low rejection sensitivity. Importantly, this relationship did not emerge in response to anger or disgust faces.

Another closely related construct to SAD is fear of negative evaluation. In fact, many researchers and clinicians would argue that this lies in the core of SAD. To examine how this psychological process contributes to threat-relevant attentional biases in SAD, Rossignol, Campanella, Bissot, and Philippot (2013) showed neutral or emotional faces (anger, fear, disgust, or happiness) to participants low and high in fear of negative evaluation while examining their brain’s event-related potentials (ERPs). Their results showed that higher fear of negative evaluation led to modulations of different stages of cognitive processing of information, indicating that this construct underlies attention biases to threatening faces.

Other underlying cognitive mechanisms that explain attentional biases to threatening faces in SAD are bound to exist. Here, I focused on only two studies that examined two such mechanisms: rejection sensitivity and fear of negative evaluation. It is intuitive why these two would be closely related to attentional biases to threatening faces: when we reject or negatively evaluate someone, this is often clearly visible in our facial expressions. It thus makes sense that those who are especially worried about rejection or negative evaluation by others, namely those with SAD, would seek out such cues in their environment (facilitated attention), linger on them (difficulty of disengagement) and subsequently avoid such situations (attentional avoidance). Now that we have explored threat-relevant attentional biases in SAD in a little bit more depth, in my next and final blog post, I will outline some exciting research on treatments that were developed to specifically target this process.

References

Burklund, L. J., Eisenberger, N. I., & Lieberman, M. D. (2007). The face of rejection: Rejection sensitivity moderates dorsal anterior cingulate activity to disapproving facial expressions. Social Neuroscience, 238-253.Cisler, J. M., & Koster, E. H. (2010). Mechanisms of attentional bias towards threat in the anxiety disorders: An integrative review. Clinical Psychological Review.

Rossignol, M., Campanella, S., Bissot, C., & Philippot, P. (2013). Fear of negative evaluation and attentional bias for facial expressions: An event-related study. Brain and Cognition, 344-352.

-

Kiersten F. Huckel is attending Seminar III. 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Giovanna Castro wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 7 months ago

-

Jacqueline J. Farah is attending Seminar III. 10 years, 7 months ago

- Load More