CEEO follows teachers on Twitter and are inspired by all the amazing photos, videos, antidotes, and reflections teachers share on Twitter every day. Mike Kulbieda, Design/Makerspace Coordinator from the International School of the Peninsula, caught our eye while searching through our Twitter feed. We asked Mike to send us some reflections on an engineering activity done in his classroom and how it went. Click “read more” below to learn about Mike’s classroom experience with an activity using LEDs, 9V batteries, and copper wire and the importance of letting students explore engineering concepts on their own and that teacher failure is just as important and acceptable as student failure in the engineering design process.

If you have a story to share about your classroom, please email it to magee.shalhoub@tufts.edu

By: Mike Kulbieda, Maker/Design Coordinator, International School of the Peninsula, Palo Alto, CA

As the Maker/Design Coordinator at the International School of the Peninsula I have the privilege of spending my days in the “makerspace” designing and facilitating lessons to encourage tinkering, exploration, collaboration, and creativity, all in service to the act of creation and skill building. I have a passion for learning by doing and as an educator have always kept that at the forefront of my teaching. Recently I reflected on a session I had with third graders in Design class on circuitry. I had placed some materials in a few boxes including batteries, small LED lights, aluminum foil, wooden sticks, pipe cleaners, and straws, and placed them in the center of each table with the idea that I would let the kids explore the materials and hopefully come to some conclusions about their relationship to each other, and how some could conduct electricity and some couldn’t. Most groups went straight for the LED light and coin cell battery and made it light up by squeezing the positive and negative leads of the light to the positive and negative terminals of the battery. Distracted by the fact that they made something light up, the other materials were left in the box untouched and unexplored. I thought to myself, “fail.” I had hoped that at least one student would make the connection between the battery, the light, and the conductive materials int their boxes in order to segue into extending electricity through circuits. No luck. What I did next, however, was the true “fail” that day. I proceeded to talk. And Draw WHILE I was talking. Until finally I saw that 20 minutes had passed and I was left with nothing more than complex diagrams on the whiteboard, yawns, and confused looks on the students’ faces. Its no wonder that when I gave them each a battery, LED, light, and some copper tape they were more clueless about what to do with it than when they arrived.

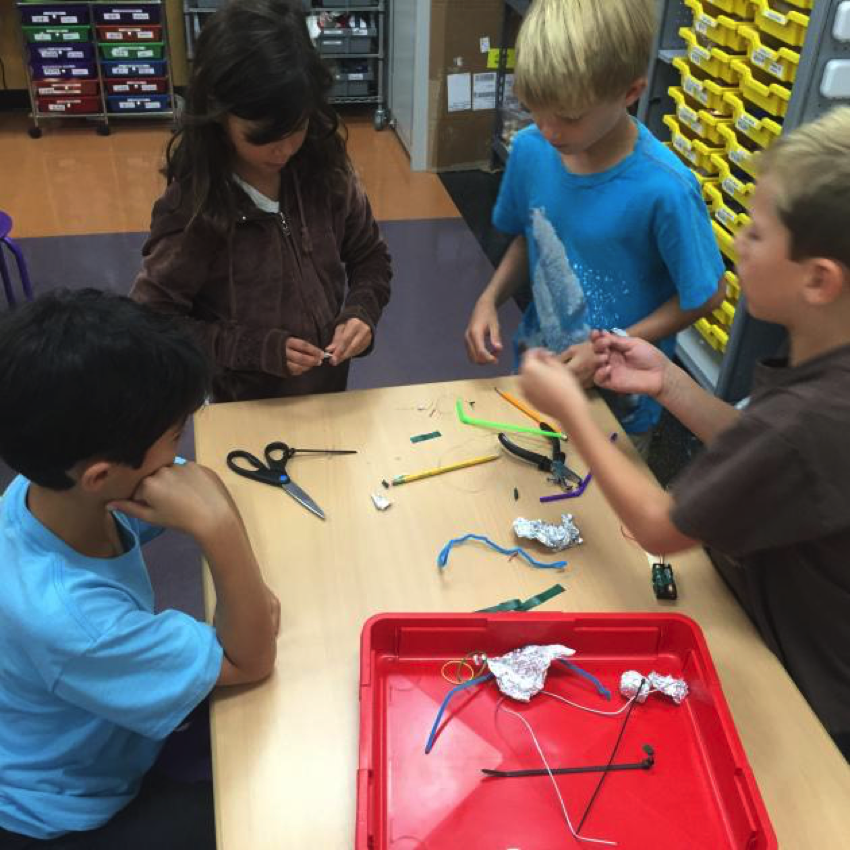

Luckily, the next day I was doing the same lesson with a different third grade class. This time I decided to change my approach, step back, and trust in the process rather than focus on the product. I gave each group the same boxes of materials as the previous groups, but this time I simply “threw the kids into the deep end” so to speak. I told them that they were to design a way to send the electricity from the battery to the LED light using the materials provided. That’s it. Ready. Go. No instruction, no diagrams, no talking. What happened next was awe inspiring. I walked around the room, listened, and watched for about an hour as each group voraciously discussed ideas, accessed and shared prior knowledge, made connections to their own experiences, tested each material, designed, failed, and redesigned until finally, one table at a time, cheers sounded around the room as each groups LED shone brightly.

Luckily, the next day I was doing the same lesson with a different third grade class. This time I decided to change my approach, step back, and trust in the process rather than focus on the product. I gave each group the same boxes of materials as the previous groups, but this time I simply “threw the kids into the deep end” so to speak. I told them that they were to design a way to send the electricity from the battery to the LED light using the materials provided. That’s it. Ready. Go. No instruction, no diagrams, no talking. What happened next was awe inspiring. I walked around the room, listened, and watched for about an hour as each group voraciously discussed ideas, accessed and shared prior knowledge, made connections to their own experiences, tested each material, designed, failed, and redesigned until finally, one table at a time, cheers sounded around the room as each groups LED shone brightly.

It’s a quick anecdote, but nonetheless tells a powerful story about how kids, when given the agency, can do so much more than we sometimes give them credit for within the confines of instruction. Taking on a “less me, more them” style allows us as teachers to  foster confidence in our students, ignite their passions, and also learn their threshold of frustration in order to support their social emotional learning. This is the power of “strategic under-instruction.” By “strategic” I mean, to use a construction analogy, build the frame, but allow them to build the walls, staircases, and floors. Let them choose the paint color, carpet, and appliances. Encourage them to design the landscaping and empower them to build an addition. Their product may not necessarily be your product, but it will be equally or more valuable, as it reflects true growth, learning, and application of knowledge.

foster confidence in our students, ignite their passions, and also learn their threshold of frustration in order to support their social emotional learning. This is the power of “strategic under-instruction.” By “strategic” I mean, to use a construction analogy, build the frame, but allow them to build the walls, staircases, and floors. Let them choose the paint color, carpet, and appliances. Encourage them to design the landscaping and empower them to build an addition. Their product may not necessarily be your product, but it will be equally or more valuable, as it reflects true growth, learning, and application of knowledge.

Takeaways:

- As teachers we have the right to fail, but we also have the ability to reflect, react, redesign, and be successful the next time, just like we expect from our students. In the words of John Dewey, “We do not learn from an experience…We learn from reflecting on an experience.”

- A “less me, more them” stance can inspire creativity, inquiry, problem solving, and collaboration.

- The word “Strategic” in “Strategic Under-Instruction” is important to recognize. It’s not sitting back at the teacher’s desk while kids “discover” and you drink your coffee. Rather, it is spending more time in the planning stages thinking about how to facilitate the journey for each student within the context of your lesson or curriculum goals.

- Be an observer. Notice how your students navigate social situations, deal with frustration, problem solve, collaborate, and handle failure in order to better understand them and address their social emotional needs.