Customer Needs Identification

Abstract

Customer Needs Identification is the process of determining what and how a customer wants a product to perform. Customer Needs are non-technical, and they reflect the customers’ perception of the product, not the actual design specifications, although frequently they are closely related. This chapter will cover methods of Customer Needs Identification, a case study, and some direct applications of identifying Customer Needs.

Background

Definition

Customer Needs Identification is the process of determining what and how a customer wants a product to perform. Customer Needs are non-technical, and they reflect the customers’ perception of the product, not the actual design specifications, although frequently they are closely related.

Figure 1

Product identification needs involves answering questions about what customers want and need. Source: Image by chainat at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Exploration

Customer Needs Identification has two major goals:

- To keep the product focused on customer needs

- To identify not just the explicit needs of the customer, but also the latent needs

These customer requirements should be independent of any particular product or potential solution. After all, it’s only after identifying Customer Needs that one can begin to meet them.

So with that in mind, the goal is to find out precisely what the customer wants. Here is a four-step method for identifying Customer Needs:

- Gather raw data from customers

- Interpret the data in terms of customer needs

- Organize the needs

- Reflect on the Process

1. Gathering Raw Data

Intuitively, the first step must be to gather data from the customers. Without their input, it would be impossible to identify their needs. “Gathering needs data is very different than a sales call: the goal is to elicit an honest expression of needs, not to convince a customer of what he or she needs” (Ulrich & Eppinger 2012 p.79). Try to learn as much as possible about the customers; the data are there to serve as guidelines for product development.

There are three recommended ways to gather data, and there is one common trap that usually provides deceptively shallow data. First, the three robust methods for collecting information:

- Interviews: Interviews are one-on-one meetings with potential customers, usually 1-2 hours in length. Frequently they take place in the customer’s own environment, as they are more comfortable there and there is a chance to see a problem in action.

- Focus groups: Focus groups are like expanded interviews. They are about 2 hours long, and they involve about 8 to 12 customers. The group is lead in a discussion by an interviewer. It is very common for the group to be watched by some number of unseen observers who take notes on the proceedings.

- Observation: Seeing someone struggle with a problem is an easy way to get a general understanding of the issue. And frequently you are not the first person to identify that problem, so “watching customers use an existing product or perform a task for which a new product is intended” is a perfectly reasonable way to identify customer needs, as well as ways in which successful companies are attempting to solve them (Ulrich & Eppinger, 2012, p.77). Observation can either be passive, where one simply watches a customer work in their natural environment, or observation can be active, where one works side-by-side with the customer and gain and understanding of their problems from their perspective.

All three of these options are excellent ways to get information from customers. If there is one pitfall of data collection, though, it would have to be written surveys. Surveys are extremely popular, but they are extremely limited. Surveys generally have very little data on the environment in which the problem is occurring, and they are fairly terrible at picking up on unanticipated needs. It’s rather difficult to write a question about a need that hasn’t been thought of yet.

If anything interesting is revealed from a survey it is very difficult to follow-up on that information. Surveys are cheap and easy to make, which is why they are so common, but time and money would be better spent on interviews, focus groups, and observation trips.

Having identified the most effective methods of gathering data, it makes sense to ask how much information needs to be collected. Griffin & Hauser (1993, pp. 1-27) have done some extensive research on that precise subject, and they found that conducting 25 interviews will usually reveal about 90% of customer needs (Ulrich & Eppinger, 2012, p.78). Some companies conduct as many as 50 interviews when preparing for a new product line; just be aware that extensive interviewing yields diminishing returns.

These interviews and focus groups are the primary means of learning about customers, so make sure to conduct interviews as effectively as possible. Here are a few suggestions that will lead to successful interviews:

- Prepare questions, but don’t be afraid to deviate if appropriate

- Use visual stimuli and props

- Suppress preconceived hypothesis about the product technology

- Have the customer demonstrate the product and/or typical related tasks

- Be alert for surprises and the expression of latent needs: pursue surprising answers with follow-up questions

- Watch for non-verbal information

When interviewing, keep an eye out for two special types of customers. The first is called a lead user. These people are customers who experience needs months or even years ahead of the market. The other type of customer is called an extreme user. These people use products in unusual ways, or they have special needs. An excellent example of an extreme user would be the wife of Sam Farber, founder of OXO, which produces the Good Grips kitchenware product lines. Due to his wife’s arthritis, Farber’s wife found it painful to use normal kitchenware. So Farber invented kitchenware specifically for his wife’s comfort. Now Good Grips is an internationally successful brand that makes handles for a wide variety of tools.

As a final comment on conducting interviews, note that there are several ways one can document the process. All interviews should be documented so that the information in them can be fully recovered. Depending on what kind of information is being sought, there are several options for documentation. Some of the more well-known choices involve audio recordings and handwritten notes, but video recordings or still photography are also acceptable.

2. Interpreting Data

After the interviews it is usually necessary to translate the vague statements of the customers into a useful list of needs. As this is a relatively subjective process, “multiple analysts may translate the same interview notes into different needs” (Ulrich & Eppinger, 2012, p.81). For that exact reason, it is beneficial to have multiple people work on the interpretations.

So how, exactly, does one transform what the customer says into something you can work with? Here is a useful process with several helpful constraints and suggestions for expressing the data.

- Write the needs in terms of what the product has to do, not how it might do it.

- Express the needs as specifically as the raw data

- Use positive phrasing

- Express the needs as an attribute of the product

- Avoid the words must and should

3. Organizing Needs

After interpreting the data, organize them. Group similar needs together, prioritize them, etc. Decide what is truly important to the customer. Define the “critical needs,” those needs which absolutely must be met before the product can be considered successful.

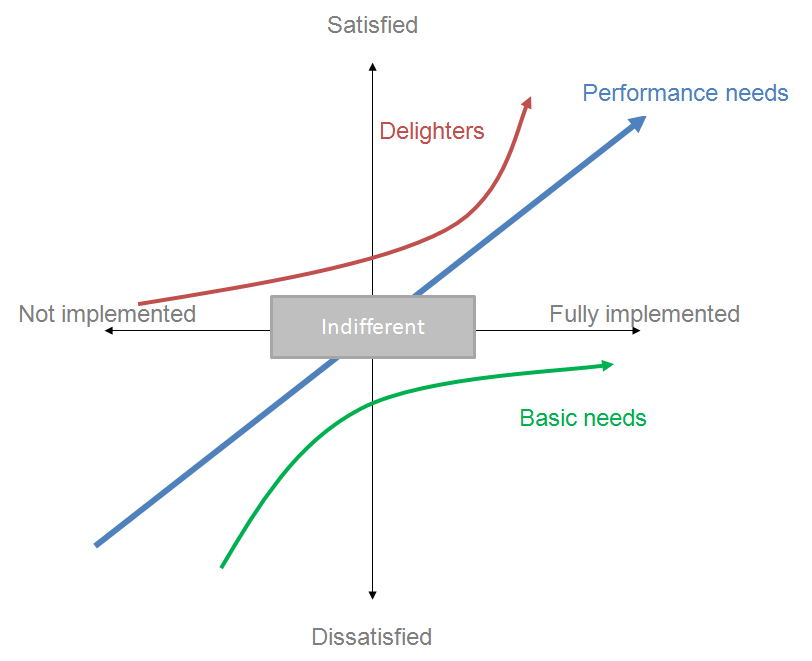

In the 1980’s Professor Noriaki Kano developed a categorization system called the Kano Method, which helps to organize needs. The essence of the Kano Method is the five Qualities that product features can have (Figure 2).

- Attractive Quality: when these product qualities are met they provide satisfaction, but when they are not met they do not cause dissatisfaction. For example, when a backpack has a separate compartment for a laptop.

- One-Dimensional Quality: when these qualities are met they provide satisfaction, and when they are not met they create dissatisfaction. For example, when the shoulder straps on a backpack are padded, they provide comfort, but when not padded they are painful.

- Must-Be Quality: these product qualities are assumed to be met, and they cause dissatisfaction when they are not met. Backpacks are expected to be able to hold books.

- Indifferent Quality: these qualities are neither good nor bad, and they do not increase nor decrease customer satisfaction when met or not met.

- Reverse Quality: The qualities cause either satisfaction or dissatisfaction when met, but it is customer dependent. For example, backpacks with a lot of compartments and pouches. Some customers really like the wealth of storage options these spaces provide, and other customers actively dislike how excessive or unmanageable those same spaces are.

Figure 1

Diagram of the Kano model. Source: Image by Craigwbrown at Wikipedia

These five qualities describe the set of customer needs and expectations that a product can meet. This set of classifications also makes it apparent why surveys can’t identify all of the customers’ needs. Customers identify needs based on dissatisfaction with a current setup or problem; a survey only contains questions about predicted or perceived problems. It can certainly find all of the one-dimensional and must-be qualities, but it will be difficult, if not impossible, to identify all of the other needs just with surveys.

4. Reflect on the Process

The final step in the Customer Needs Identification process is to reflect on what’s been done. Consider the statements that have been gathered and study the interpretations. Try to evaluate how the process was executed. Have all types of customers been interviewed? Do any customers require follow-up interviews? Are any of the needs surprising?

Look for ways to improve or refine the Customer Needs Identification process. Would more interviews help? Less? How about focus groups? Could the process have been done faster? Every project will have different answers to these questions, but taking the time to consider this particular process will help to prepare for the next one.

Remember, as of now there are no product specifications! This entire process is about identifying needs, not designing solutions. That comes later.

Example: Ergonomic Screwdrivers

DevCo, a well-established tool manufacturer (renamed for the purpose of this example), was looking to enter the growing market of handheld power tools by developing a cordless screwdriver. DevCo conducted 30 interviews to get a precise idea of what their customers wanted.

Here are some sample responses from the customers:

- I need to drive screws fast

- I like the pistol grip

- I want to be able to use it when the batteries are dead

- I can’t drive screws into hard wood

Based on these responses, and many, many others, DevCo was able to create a list of Interpreted Needs. Here are the interpretations used to design the screwdriver:

- The screwdriver drives screws faster than by hand

- The screwdriver grip is comfortable

- The user can apply torque manually to the screwdriver to drive a screw (*)

- The screwdriver drives screws into hard wood

All of these interpretations, which are written in an affirmative style, helped to guide the engineers. The need with the asterisk denotes a latent need, something previously unnoticed but clearly representing a problem many people would identify with.

DevCo then organized the needs according to their level of importance, frequency of appearance, etc., after which they developed a highly successful cordless screwdriver. Thanks to an extensive Customer Needs Identification process, DevCo was able to clearly define the goals and restrictions on the screwdriver so that engineers could implement a proper design.

Case Study: The Electrostatic Printer

By now I hope it is obvious just how helpful it can be to properly identify Customer Needs. However, it is hard to state just how important the process really is, and how dangerous it can be to neglect it. This example comes from the Harvard Business School. In 1969, the company Ink, Inc. (renamed for the purpose of this case study) released a high-speed electrostatic computer printer called the Inked 3000. It was the first electrostatic printer on the market! It could print four times faster than the next closest competitor, and it cost one-fourth as much. Printers were fairly common at this point, and the Inked 3000 looked like it would take the market by storm.

But this is not a success story, and that is not what happened. The printer got to market but nobody was interested. Ink had simply assumed that people would be interested in a faster, cheaper version of what they already had. It sounds like a reasonable assumption. But no matter how reasonable it sounds, it was still an assumption, totally unfounded by market research, and Ink, Inc. was being punished for not doing their homework. Here are just a few of the many small problems that turned a remarkable technological breakthrough into a total flop.

The Inked 3000 used 8.5 X 11 inch paper, for one thing; while that sheet size is normal today, most people at the time were using 14 X 17 inch paper. Also, the 3000 was fed with rolls of paper, as opposed to the fan-folded paper that was popular then. On top of that, the rolls were only 300 feet long. For household use that’s more than enough. But the primary consumers were businesses! They printed so many pages that they used up an entire 300 ft. roll of paper in five minutes!

This just goes to show that even if your product is brilliant, effective, and cheap, if it doesn’t solve a problem then it isn’t worth buying. Ink, Inc. could have established themselves as a dominant force in the printing market, but instead they lost the majority of their investment.

Student Focus: How Does This Apply to You?

Customer Needs Identification defines the problem that an engineer needs to solve. Remember, “the greatest defect a product can have is not satisfying the customer” (Lasser 2013). An excellent example of how Customer Needs determine the scope of a project comes from the ECE Red Team’s Senior Project for an Autonomous Reconnaissance Drone. The drone is a quad-copter which flies to a bridge, collects data from sensors on the bridge, and returns to its docking station with the data. Those are the only tasks that the customer specified for the drone; it would be too easy to scope the project larger. Why not have the drone interpret the data and take pictures when necessary? Why not give the drone the ability to perform minor maintenance on the bridge? Why not have the drone fly to altitudes over 30,000 ft.?

Quite simply, the customer doesn’t want that. The drone absolutely must meet the specifications of the customer, and all of those extra features don’t contribute to the customer’s appreciation of the product. Time spent working on those features is time taken away from the critically important ones, and even assuming that we meet all of the necessary requirements, adding the extra features takes time and money that could be put to other uses. Now, it’s important to anticipate needs that the customer might not have recognized, but it’s equally important not to tack on frivolous features. An example of a useful addition would be an antenna to boost the communication range of the drone. The drone needs to reliably collect data from sensors on a bridge. If it cannot hover with enough stability to communicate with the sensors, then an antenna would correct that problem. The antenna anticipates a problem that the customer cares about and works to pre-emptively correct it. The other examples do not, at least not until bridges are made 30,000 feet tall.

Cited References

- Cooper, R.(1992). Winning at New Products. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. OCLC WorldCat Permalink: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/27726156

- Griffin, A., & Hauser, J. R. (1993). The Voice of the Customer. Marketing Science, 12(1), 1–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/183735

- Lasser, R. (2013, January 18). Notes from Lecture One. Retrieved from online course website, Tufts University.

- Shiba, S., Graham, A., Walden, D., Lee, T. H., Stata, R., & Center for Quality Management (Cambridge, Mass.). (1993). A new American TQM: Four practical revolutions in management. Cambridge, Mass: Productivity Press. OCLC WorldCat Permalink: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/227897718

- Ulrich, K. T., & Eppinger, S. D. (2012). Product design and development . (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. OCLC WorldCat Permalink: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/706677610

Recommended Reading

- Cooper, R. G., & Edgett, S. J. (2007). Generating breakthrough new product ideas: Feeding the innovation funnel. Ancaster, Ont.: Product Developemnt Institute. OCLC WorldCat Permalink: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/132284042

- Cagan, J., & Vogel, C. M. (2013). Creating breakthrough products: Revealing the secrets that drive global innovation. Upper Saddle River, N.J: FT Press. OCLC WorldCat Permalink: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/795687211