Neurosurgery is by no means a modern invention. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is instead a result of millennia of humans trying to impact behavior and health by physically altering the brain. The first post in this blog gave an overview of what DBS is and why it is used. This post will briefly cover the history of neurosurgery; looking at the advances that lead to DBS as a viable therapeutic method.

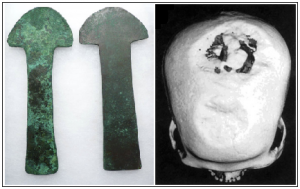

Trepanning: Trepanning was a widespread phenomenon. The left image shows tools used in the procedure from South America in the first millennium. The right image show a Neolithic skull from 5100 with evidence of the procedure (Robinson et al., 2012)

The earliest example of neurosurgery that we have evidence of is trepanning. This was the practice of drilling a hole in the skull in order to relieve a patient of some malady. Some postulate it was thought that demons causing psychological symptoms needed to be released. The earliest example is a Neolithic burial in Alsace France, dating to 5100BC. The holes in the skull have evidence of healing, suggesting that it was done intentionally, and not a result of an accident (Robinson et al., 2012). Even the idea of stimulating the brain as a medical treatment is not novel. Scribonius Largo, a roman physician in 46 AD applied electric eels to patient’s foreheads and reportedly demonstrated amelioration of headaches(Sironi, 2011).

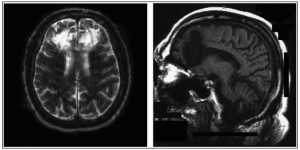

Frontal Lobotomy. Axial and sagittal views of a lobotomy. Notice the diffuse damage in the images, most notably the bright white swath across both hemispheres on the left. (Lapidus, 2013).

Functional neurosurgery had a resurgence around the First World War. Mental asylums were packed, a situation made worse war veterans returning home and a lage number advanced syphilis cases before penicillin was discovered. This environment influenced the development and popularization of the frontal lobotomy by Egas Moniz and Walter Freeman. The transcranial frontal lobotomy had severe consequences for patients. They often showed a reduction of their initial psychological symptoms, but at the cost of extreme apathy and personality defects. The demure state of these patients meant less work for mental institutions, but the procedure soon became obsolete under a critical public eye (Robinson et al., 2012).

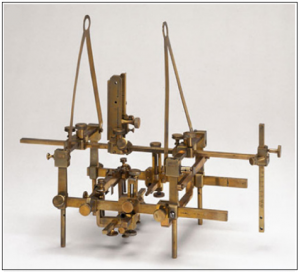

A stereotaxic device: An early example of a stereotaxic device from 1908. The first human stereotaxic experiments were not done until 1947(Robinson et al., 2012).

The next frontier in neurosurgery was ablative therapy. This was the lesioning, often by radioactive rods, of areas in the brain. Initially a crude procedure, it was refined with the the advent stereotaxic technique in 1947. Stereotaxic technique is the practice of holding the head in a fixed position, and then using reference points on the brain, skull, imaging techniques and prior knowledge of brain mapping to precisely access areas of the brain. This technique saw the rise of lesions as an effective treatment for many disorders (Sironi, 2011)

Stimulation of the periventricular/periaqueductal grey matter as well as some areas of the thalamus was demonstrated to be extremely effective at controlling pain that was difficult to treat pharmaceutically (Kumar et al., 1990). In large part due to these treatments, it was shown that high frequency electric currents had a similar effect as ablative therapies. At the time, surgeons were treating tremor disorders and Parkinson’s disease by thalamotomy, or destruction of areas of the thalamus. While this treatment improved symptoms, it often caused dysarthria, an issue with the motor control of speaking. The stimulation of DBS was shown to be as, if not more, effective that ablation, with fewer side effects, and less surgeries needed (Tasker 1998). Further evolution of the technique looked at specific nuculi of the thalamus as well as the palladium (Limousin-Dowsey et al., 1999).

This prior body of scientific work lead to excitement about the use of DBS and the exploration of how it could be used in treating other neurological and psychiatric disorders. Obsessive disorders were among the first affective disorders to be treated in the early 21st century. The role of DBS in depression therapies has only very recently been studied (Lapidus et al, 2013). The background of neurosurgery is necessary to establish the context in which current research of depression is operating. We will examine the current theories and specifics of deep brain stimulation for depression in our next post.

References:

Kumar, K., Wyant, G., & Nath, R. Deep brain stimulation for control on intractable pain in humans, present and future: A ten-year follow-up. (1990). Neurosurgery, 26(5), 774-782. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

Lapidus, K., Kopell, B., Ben-Haim, S., Rezai, A., & Goodman, W. (2013). History of Psychosurgery: A Psychiatrist’s Perspective. World Neurosurgery, 80, S27.e1-S27.e16. Retrieved September 26, 2014, from PubMed.

Limousin-Dowsey, P., Pollak, P., Van Blercom, N., Krack, P., Benazzouz, A., & Benabid, A.(1999). Thalamic, subthalamic nucleus and internal pallidum stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology, (246), 42-45. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

Robison, R., Taghva, A., Liu, C., & Apuzzo, M. (2012). Surgery of the Mind, Mood, and Conscious State: An Idea in Evolution. World Neurosurgery, 77, 662-686. Retrieved September 26, 2014, from PubMed

Tasker, R. (1998). Deep Barin Stimulation is Preferable to Thalomotomy for Tremor Suppression. Functional Neurosurgery, (49), 145-154. Retrieved October 23, 2014.