Welcome back!

To begin with a brief recap, the themes I have presented thus far under my topic of “Failures of Empathy” have ranged from the goals that drive ordinary individuals to attenuate empathic concern towards others, to the empathic deficits (both neural and psychological) that ultimately define certain abnormal behaviors. Today, I will be returning to a context that *unfortunately* seems to ubiquitously drive people to demonstrate failures of empathy: intergroup contexts.

The concept of ‘intergroup’ can be parsed into two terms: ‘ingroup’ and ‘outgroup’. These terms refer to numerous examples of group memberships, in which an ‘ingroup’ is a group to which an individual belongs, and an ‘outgroup’ is a group to which the individual does not belong. These can range from relatively socially-constructed groups, such as sports teams or sororities, to more cultural and stable factions, such as ethnic or religious groups. Often occurring in intergroup contexts are processes known as ‘ingroup favoritism’ (preferring one’s ingroup) and ‘outgroup derogation’ (disfavoring one’s outgroup).

Most of the research on failures of empathy in intergroup contexts has focused on racial ingroups and outgroup— and for good reason. There is something particularly potent about the social category of ‘race’ that especially drives us to favor our ingroup and derogate our outgroups. The large, and robustly demonstrated, discrepancy between empathic concern for our ingroups vs. outgroups has received so much attention in the literature as of late that it recently was termed the ‘intergroup empathy gap.’

Before neuroscientific methods were common in social psychology, a clever study by Johnson et al. (2002) demonstrated how failures of empathy within a racial intergroup context can result in very real-world implications. In this study, White participants acted as jury members in a mock trial for either a Black or a White defendant accused of the exact same crime. When the defendant was Black, versus White, the participants reported feeling less empathy for the defendant, made more attributional rationales about the defendant’s wrongdoing (assumed the crime was committed due to the personality of the defendant, rather than the characteristics of the situation), and ultimately assigned harsher punishments. Remember: the mock White and Black defendants were accused of the same exact crime.

A few years later, social and affective neuroscience researchers began to examine the neural bases behind this phenomenon. The first of these studies by Xu et al. (2009) explored how viewing ingroup vs. outgroup members in pain would differentially activate empathic concern. They showed White and Chinese participants photographs of both White and Chinese individuals in painful and non-painful contexts. Thus, all participants (whether White or Chinese) viewed members of both their racial ingroup and their racial outgroup in typical empathy-inducing situations. Results showed that a neural region typically involved in empathy, the anterior cingulate cortex, was far more activated when participants viewed ingroup vs. outgroup members in pain.

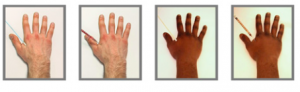

Perhaps, however, the effect demonstrated in this Xu et al. (2009) study was simply due to factors related to unfamiliarity. That is, because members of your racial outgroup are likely perceived a less similar to you, it may simply be more difficult to activate empathic concern for dissimilar others. A study conducted by Avenanti et al. (2010) addressed this possibility. They utilized a similar paradigm as Xu et al. (2009), showing Black and White participants photographs of Black and White individuals in pain. They added, however, a third set of photographs: individuals with violet–colored skin tone in pain (see below). If racial outgroup members represent relatively unfamiliar/dissimilar targets, the violet-colored individuals should denote entirely unfamiliar/dissimilar targets. Using transcranial magnetic stimulation, researchers examined the degree to which target pain activated sensorimotor reactivity—or the degree to which people experienced the targets’ pain as though they were experiencing the pain themselves. Astoundingly, results demonstrated that both Black and White participants exhibited neural empathic reactivity when viewing the pain of both their ingroup members AND the unfamiliar violet- group members. No such reactivity was evident when viewing racial outgroup members in pain. Thus, the unfamiliarity account does not seem to sufficiently explain the intergroup empathy gap.

So why does all of this matter? So what if a tiny region in a person’s brain activates less in response to some people over for others? Above, I mentioned one study that demonstrated how the intergroup empathy gap could potentially have negative real-world implications. Regrettably, one does not need to search long and hard for examples of this in our lives today. Following the recent shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri, a typical pattern emerged in the media. Justifications akin to victim-blaming were released in the days following the incident, ranging from speculation about his drug-use, to the possibility that he stolen cigarettes just prior to his murder. One fact ironically remained clear during these media updates: Michael Brown was unarmed.

In the midst of this shooting, people on social media began to expose an even more disturbing pattern evident in the mainstream media: more favorable treatment of White murders than for Black victims. Like in the example below, White murders are ironically often depicted as victims, and Black victims as bullies. See this link for copious examples of the treatment of Black victims vs. White murders in the media. In my opinion, this is the ultimate display of ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation via the intergroup empathy gap.

as victims, and Black victims as bullies. See this link for copious examples of the treatment of Black victims vs. White murders in the media. In my opinion, this is the ultimate display of ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation via the intergroup empathy gap.

In this post, I have described how both neuroscientific and psychological evidence demonstrate how people tend to experience less empathic concern for members of their outgroups versus members of their ingroups. While the extant literature on this topic is ample, there still remain several important questions. We now know that this happens… but why? My own work seeks to understand the specific mechanisms behind this discrepancy. Does decreased empathic concern towards outgroup members occur automatically, or is it the product of certain regulatory strategies? In the case of the Michael Brown shooting, did the public effortlessly feel less empathic concern for this black murder victim, or did they work to prevent any activated empathy from becoming compelling? If so, were the justifications made about his murder one means of regulating any existing empathic concern? Stay tuned (well, for years to come) for some answers— hopefully!

——————————–

- Avenanti, A., Sirigu, A., and Aglioti, S. M. (2010). Racial bias reduces empathic sensorimotor resonance with other-race pain. Current Biology, 20, 1018–1022.

- Johnson, J.D., Simmons, C.H., Jordan, A., McLean, L., Taddei, J., Thomas, D., et al. (2002). Rodney King and O.J. Revisited: The Impact of Race and Defendant Empathy Induction on Judicial Decisions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(6), 1208-1223.

- Xu X, Zuo X, Wang X, Han S. (2009). Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 8525-8529.

- [Photo of Media Treatment]. Retrieved November 18, 2014 from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08/14/media-black-victims_n_5673291.html