Last blog we discussed the ways in which affective abilities are varied in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients, the affective chicken as it were. Now let’s discuss some of the other cognitive differences seen within OCD, the “cognitive egg”.

Seen here: cognitive egg

Let’s start with Decisions

One strong cognitive difference between patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and healthy controls is a diminished ability to make goal-directed decisions (Gillan, 2014). Some researchers, such as Gillan et al in their 2014 paper, discuss how the inability to control compulsive actions can be seen as an inability to make goal-directed decisions, where, for example, instead of deciding to leave the house by flipping the light switch once in order to reach their goal of making it to work on time, some patients with OCD will decide to flip the switch numerous times in accordance to their compulsion.

Gillan et al wanted to see if this impairment was due to a disruption in the balance between goal-directed action control and habitual behaviors, such as compulsive behaviors (Gillan, 2014). They found that obsessive-compulsive disorder patients showed decision making that suggests they based decisions on the temporally present expected value, instead of taking into account other possibilities (would it have been better to choose the other option?) (Gillan, 2014). They highlighted that this is similar to patients with lesions to the OFC, suggesting that perhaps that region is significant for OCD decision-making (Gillan, 2014). They also found that OCD patients reacted more emotionally, consistent with affective differences discussed in my previous post.

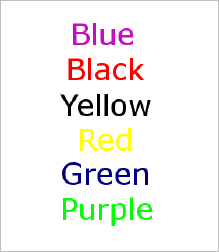

Cognitive Conflict – Stroop Task

Another difference for OCD patients comes in the form of conflict monitoring and error detection. The theory is that obsessions are caused by an overactive conflict/error signal that is constantly signaling something is wrong despite other evidence (Stern & Taylor, 2014). This error detection can be seen cognitively during tasks where there’s a mismatch between what the person normally would do and what is required (Stern & Taylor, 2014).

This leads us to the Stroop Task! You are asked to say what color the font of the word is, when your automatic instinct is to read the word itself. Go ahead and give these a try!

While there is a clear difference in the results (OCD patients tend to do worse at these tasks than controls), the actual neural process for OCD patients is unclear at present. Some found hyperactivity in the medial frontal cortical (MFC) regions during conflict, while others found reduced activity in the MFC, while still others found no difference (Stern & Taylor, 2014). Other areas found to differ include the parietal cortex, the temporal cortex, and the striatum (Stern & Taylor, 2014).

Executive Control and Task Switching

OCD patients also differ in executive control, and are found to have a decrease in overall executive functioning abilities (Lewin et al, 2014). More specifically, the capacity to switch tasks, which includes executive functions such as attention and decision-making, has been theorized as a possible explanation for obsessions and compulsions (Stern & Taylor, 2014). Studies during cognitive switching tasks have found that OCD patients show reduced activity in the frontal-parietal network (FPN), indicated in executive function and task control, as well as reduced activity in the OFC, temporal cortex, and others (Stern & Taylor, 2014).

Combining the Chicken and Egg

This evidence of cognitive variation, along with the evidence of affective variation, paints a complex picture of OCD, where it is still unclear whether affect or cognition is the true initial cause of the disorder. However, it is clear that both affective brain regions, such as the orbitofronto-striatal system, and cognitive brain regions such as the OFC, frontal-parietal network, and MFC, are involved in the complexity that is obsessive-compulsive disorder (Kashyap et al, 2013).

What’s Next?

The final blog will step away from the question of what makes up OCD, and will instead focus on a question more important to patients with the disorder itself: how can we treat this?

Sources:

Gillan, C.M., Morein-Zamir, S., Kaser, M., Fineberg, N.A., Sule, A., Sahakian, B.J., Cardinal, R.N, & Robbins, T.W. (2014). Counterfactual processing of economic action-outcome alternatives in obsessive-compulsive disorder: further evidence of impaired goal-directed behavior. Biological Psychiatry 75, 639-646. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.018

Kashyap, H., Kumar, J.K, Kandavel, T., & Reddy, Y.C.J (2013). Neuropsychological functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: are executive functions the key defecit? Comprehensive Psychiatry 54, 533-540. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.003

Lewin, A.B., Larson, M.J., Park, J.M., McGuire, J.F., Murphy, T.K., & Storch, E.A. (2014). Neuropsychological functioning in youth with obsessive compulsive disorder: an examination of executive function and memory impairment. Psychiatry Research 216, 108-115. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.014

Stern, E.R., & Taylor, S.F (2014). Cognitive neuroscience of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 37, 337-352. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2014.05.004

Image Sources:

https://stillthinkingagain.wordpress.com/2009/07/

http://www.braintraining101.com/take-the-stroop-test/