by Dzheveira Karimova

The research trip to Mexico City was an immense success, both for my academic goals and personal growth. Throughout my stay, I was captivated by the city’s vibrant culture and the warmth of its people. The continuous friendliness, hospitality, and kindness we experienced—from the locals at the markets to the individuals I interviewed—were truly heartwarming.

My research centers on migration trends to Mexico City, examining its role as a crucial hub for refugees and migrants en route to the United States. Additionally, I investigate the resources available to these individuals and the contributions of the government, NGOs, and civil society in supporting them.

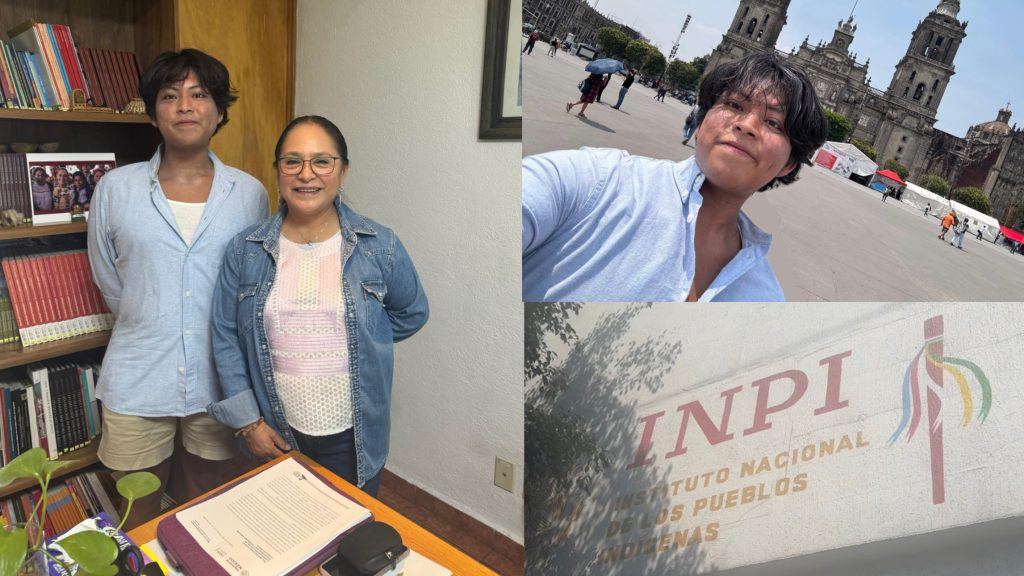

During my trip to Mexico City, I had the honor of interviewing esteemed professors, researchers, and activists at local universities. I am deeply grateful to Dr. Tigau, Professor Diaz, and Dr. Zavala de Cosío for meeting with me at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and El Colegio de México. Our conversations were incredibly informative, shedding light on current migration trends, the growing impact of the city’s water crisis on migration attitudes, the effects of the CBP One application, and the influence of both Mexican presidential debates and the upcoming US elections on migration policies and trends.

Mexico City afforded me incredible opportunities to connect with esteemed professionals and inspiring individuals in the field of migration. After taking a chance and emailing the general address of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Mexico, I was thrilled to receive a reply from Emilio Gonzalez, Senior Protection Assistant, and Alejandra Carillo, Head of the Mexico City Field Unit, regarding an interview. It was an honor to speak with such experts at the forefront of addressing migration issues in the city. Through our discussion, I gained valuable insights into recent migration from Venezuela, Central America, Haiti, and Afghanistan. Learning about UNHCR’s efforts in Mexico City, including their support for local organizations and advocacy within the government to increase awareness and support for migration challenges, was an extraordinary opportunity and is extremely valuable for my research.

The highlight of my research trip was visiting La Casa Tochan, the first migrant shelter in Mexico City. During my visit to this remarkable shelter, I had the privilege of interviewing Gabriela Hernández, the director and coordinator. Founded in 2011 due to the city’s lack of support for migrants, the shelter emerged from a collective effort by various organizations to provide accommodation and assistance when the government failed to do so. Gabriela shared insights into the growing migrant crisis in the city and the government’s inadequate response in opening new shelters to accommodate the increasing migrant and refugee population. We also discussed the shelter’s dynamics, with refugees arriving from Central America, Venezuela, Haiti, Afghanistan, Kurdistan, and China, and how the dedicated staff, including nurses, psychologists, and lawyers, manage to assist them despite language barriers. The visit to the shelter was truly inspiring. Conversations with Gabriela, the shelter staff, and volunteers were not only touching but also highly informative. Their dedication and perseverance in helping refugees in the city, despite the lack of funding and resources, is truly remarkable.

I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to conduct such vital research in Mexico City, and I am deeply thankful for this life-changing experience.