Chapter 4: Military Activities in an EEZ

Military Activities in an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

In May 2016, following a “dangerous” intercept by two Chinese J-11 fighter jets that approached within 50 feet of an U.S. EP-3 Aries reconnaissance aircraft, China’s Foreign Ministry demanded that the U.S. immediately cease surveillance flights over international waters along China’s coast, saying they were “seriously endangering Chinese maritime security.”1 After a similar incident in June 2016, Secretary of State John Kerry said the U.S. would consider any Chinese establishment of an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea to be a “provocative and destabilizing act.”2 This dispute is but one example of a coastal State unlawfully trying to limit military activities within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Introduction

The legal definition of the EEZ and a discussion of the relevant articles of the LOSC that delineate the rights, jurisdiction, and duties of coastal States are included in Chapter Two: Maritime Zones. This chapter outlines the relevant articles of the LOSC that delineate the rights and duties of other States within the EEZ of a coastal State. It then addresses the legality of military activities within an EEZ and differing interpretations of the law promoted by certain States. Finally, it highlights sensitive reconnaissance operations in the EEZs of other States conducted by U.S. Armed Forces with a focus on publicized incidents relevant to U.S. national security interests and foreign policy.

Rights and Duties of States Other Than the Coastal State Within an EEZ

Article 87 of the LOSC provides that the high seas are open to all States, including freedom of navigation and overflight, and that the freedoms of the high seas “shall be exercised by all States with due regard for the interests of other States in their exercise of the freedom of the high seas, and also with due regard for the rights under this Convention with respect to activities in the Area.” 3 Article 58 recognizes that all States enjoy within the EEZ “the freedoms referred to in Article 87 of navigation and overflight and of the laying of submarine cables and pipelines, and other internationally lawful uses of the sea related to these freedoms, such as those associated with the operation of ships, aircraft and submarine cables and pipelines, and compatible with the other provisions of this Convention.” Article 86 of the Convention confirms this broad interpretation of Article 58. Hence, both the EEZ (including the contiguous zone) and the high seas beyond the EEZ are often referred to as “international water”or “high seas” for purposes of such navigation and overflight rights. Article 301 requires States to “refrain from any threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the principles of international law embodied in the Charter of the United Nations” and also applies to EEZs.

Legality of Military Activities in an EEZ

Most of the States that participated in the LOSC negotiations supported the view that military operations, exercises, and activities have always been regarded as internationally lawful uses of the sea and that the right to conduct such activities would continue for all States within the EEZs of other States.4

Air Defense Identification Zones (ADIZ)

However, international law does not prohibit coastal States from establishing ADIZs for security reasons in the international airspace within their EEZ. For example, an aircraft approaching national airspace may be required to identify itself while in international airspace as a condition of entry approval. ADIZs are justified in international law on the basis that a State has the right to impose reasonable conditions for entry into its national airspace. States that have standing ADIZs include Indonesia (over the island of Java), U.S., Japan, Canada, and France.5 U.S. ADIZs are set forth in 14 CFR 99.42, 99.43, 99.45, and 99.47 for the continental U.S, Alaska, Guam, and Hawaii respectively.6

Certain States, however, purport to require all aircraft penetrating an ADIZ to comply with ADIZ identification procedures, whether or not the aircraft intends to enter their national airspace. The U.S. does not recognize the right of a coastal State to impose ADIZ procedures upon foreign aircraft that do not intend to enter national airspace. Accordingly, U.S. military aircraft not intending to enter national airspace do not identify themselves or otherwise comply with ADIZ procedures established by other States, unless the U.S. has specifically agreed to do so.7

Surveillance and Intelligence Activities Within EEZs Are Legal

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has argued that U.S. surveillance flights for the purpose of overt intelligence collection within China’s EEZ “undermine the international peace and security” of the EEZ and are therefore a violation of international law.8 China has referenced articles 87, 88, and 301 of the LOSC in its argument and stated that the “right to maintain peace, security, and good order” within the EEZ, shall be respected and that a State shall conform to the LOSC and “other rules of international law when exercising its freedom of the high seas.”9 The U.S. view is that any activity that occurs in international airspace should be treated as legal, unless it involves hostilities against another State, and therefore the use of passive systems to collect information from an area not subject to national jurisdiction is entirely peaceful and lawful.10 Examples from the tense and sometimes dangerous international relations between China and the U.S. related to this dispute about military activities within China’s EEZ will be discussed further in the final section of this chapter.

Military Marine Data Collection (Oceanographic Surveys) Within an EEZ Are Legal

Coastal States may regulate marine scientific research (MSR) within their EEZ in accordance with Article 56 of the LOSC. States that attempt to limit military marine data collection (surveillance operations and oceanographic surveys) in EEZs have argued that such operations are akin to MSR and thereby subject to coastal State control.11 These attempts by coastal States to regulate military marine data collection are inconsistent with centuries of state practice, customary international law, and the text of the LOSC Articles 58, 86, and 87.12 Restrictions on MSR were adopted in connection with the adoption of the EEZ. Based on the language and legislative history of the Convention, these restrictions were intended to limit research activities by foreign States regarding maritime resources and were not intended to limit military marine data collection.

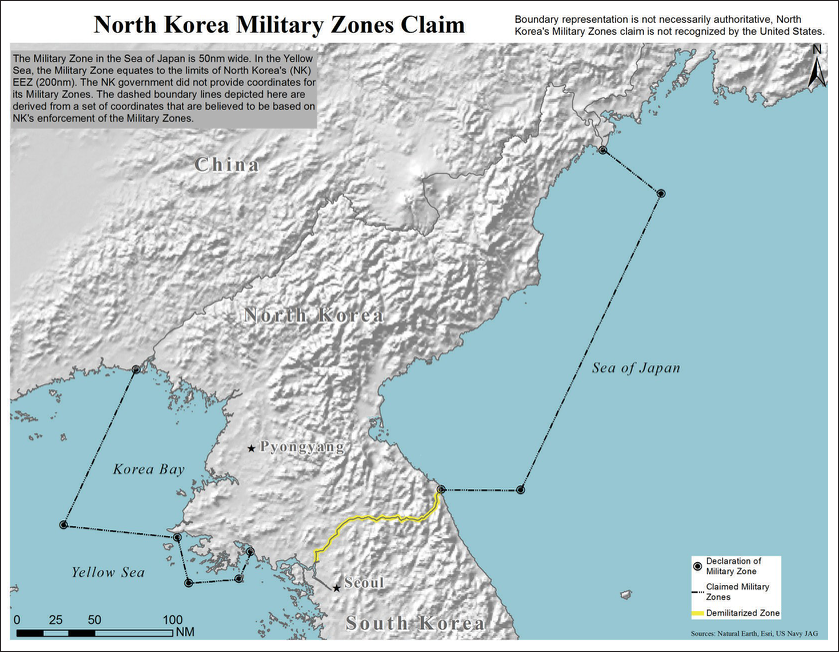

North Korea’s Unlawful Approach

North Korea also does not respect freedom of navigation within its EEZ and it aggressively opposes military activities such as intelligence collection flights within its EEZ. On August 1, 1977, North Korea declared a “military zone” extending 50 miles from the starting line of the territorial waters in the East Sea to the boundary line of the economic sea zone in the West Sea for the purpose of safeguarding its EEZ and to defend the “nation’s interests and sovereignty.”13 Foreign military ships and aircraft are prohibited from entering the zone and civilian ships and aircraft are allowed to navigate inside it only with prior agreement or approval. It is also strictly prohibited to take photographs or collect marine data.14 North Korea is effectively treating this area as internal waters and national airspace.

Other Unlawful Coastal State Restrictions on Military Activities Within an EEZ

Eighteen States purport to regulate or prohibit foreign military activities in their EEZs, but of these only China, North Korea, and Peru have demonstrated a willingness to use force to impose their excessive EEZ claims. A list of the most common of these unlawful constraints is provided below:

- Restrictions on “non-peaceful uses” of the EEZ without consent, such as weapons exercises;

- Limitations on military marine data collection (military surveys) and hydrographic surveys without prior notice and/or consent;

- Requirements for prior notice and/or consent for transits by nuclear-powered vessels or ships carrying hazardous and dangerous goods, such as oil, chemicals, noxious liquids, and radioactive material;

- Limiting warship transits of the EEZ to innocent passage;

- Prohibitions on surveillance operations (intelligence collection) and photography;

- Requiring warships to place weapons in an inoperative position prior to entering the contiguous zone;

- Restrictions on navigation and overflight through the EEZ;

- Prohibitions on conducting flight operations (launching and recovery of aircraft) in the contiguous zone;

- Requiring submarines to navigate on the surface and show their flag in the contiguous zone;

- Requirements for prior permission for warships to enter the contiguous zone or EEZ;

- Asserting security jurisdiction in the contiguous zone or EEZ;

- Application of domestic environmental laws and regulations; and

- Requirements that military and other State aircraft file flight plans prior to transiting the EEZ.

A complete list of the unlawful restrictions imposed by coastal States upon military activities in an EEZ can be found in the Maritime Claims Reference Manual (MCRM) issued by the Department of Defense (DoD) Representative for Ocean Policy Affairs (REPOPA) published at the following website: www.jag.navy.mil/organization/code_10_mcrm.htm.

These claims have no basis in customary international law, State practice, the LOSC, or the Chicago Convention on international civil aviation. These claims have been protested against and operationally challenged by the U.S. through its Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program.15 Additional information about the FON Program can be found in Chapter Three: Freedom of Navigation.

U.S. Sensitive Reconnaissance Operations in the EEZ of China

The U.S. military conducts intelligence collection flights, often referred to as “sensitive reconnaissance operations (SRO),” within the EEZs of foreign States that are sometimes challenged and intercepted by foreign military aircraft. Perhaps the most infamous of these incidents occurred on April 1, 2001 off the southern coast of China near Hainan Island when a Chinese F-8-II “Finback” fighter made contact with a U.S. EP-3E Aries aircraft. The Chinese pilot died after his fighter crashed into the sea and the American EP-3E was severely damaged and had to make an emergency landing on Hainan Island.16

These dangerous intercept incidents have continued over the years as Chinese aircraft have attempted to deter the U.S. aircraft from approaching China’s coast to utilize sophisticated intelligence-collection capabilities. More recently, on August 22, 2014, the Obama administration accused a Chinese fighter jet of conducting a “dangerous intercept” of a U.S. P-8 Poseidon surveillance aircraft near Hainan Island, and U.S. officials said it was at least the second formal complaint U.S diplomats have filed with China in recent months.17 A similar series of events occurred in May and June of 2016 when two Chinese fighter jets that flew within 50 feet of a U.S. EP-3 aircraft over the South China Sea, and a Chinese J-10 fighter jet conducted a dangerous intercept of a U.S. reconnaissance plane over the East China Sea . The U.S. determined that China’s dangerous intercepts were in violation of an agreement designed to reduce or avoid such incidents that was signed by the two governments in 2015.18 On February 8, 2017 near Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea, a Chinese KJ-200 aircraft approached within 1,000 feet of a U.S. P-3 Orion, and the P-3 had to alter its course to avoid a collision.19 The status of the Scarborough Shoal and the area around it within the context of the LOSC were an important part of the dispute between China and the Philippines, which is discussed in Chapter Ten: The South China Sea Tribunal.

Conclusion

The preservation of military activities in EEZs will continue to be of paramount importance to the U.S. and is a source of continuing friction with coastal States that seek to expand their authority in their EEZs. The U.S. should continue FON Operations, diplomatic protests, military exercises, and SROs to challenge the unlawful limitations that coastal States seek to impose on military activities.

- Idrees Ali and Megha Rajagopalan, “China demands end to U.S. surveillance after aircraft intercept”, Reuters (May 19, 2016) (available at: http:// www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-china-usa-idUSKCN0YA0QX).

- Reuters, “Pentagon U.S. Accuses China of Dangerous, High-speed Intercept of Spy Plane in South China Sea”,Newsweek (June 7, 2016) (available at: http://www.newsweek.com/china-spy-plane-intercept-unsafe-south-china-sea-united-states-high-speed-asia-467714).

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Article 87, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397 [hereinafter LOSC]. (available at: http://www.un.org/ depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part2.htm) (A definition of the Area can be found in Chapter Two: Maritime Zones).

- 17 Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea, Plenary Meetings, Official Records, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.62/WS/37 and ADD. 1-2, 244 (1973-1982).

- Richard Jaques, Maritime Operational Zones, U.S. Naval War College, D-4 (2013). [hereinafter Richard Jacques, Maritime Operational Zones] (available at: https://www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/Departments—Colleges/International-Law/Maritime-Operational-Zones/2013-Zones-Manual-(1).pdf.aspx)

- Richard Jacques, Maritime Operational Zones, Note 9 at 3-3.

- “Air Force Operations and the Law”, The Judge Advocate General’s School, 78 (2014). (available at: http://www.afjag.af.mil/Portals/77/documents/AFD-100510-059.pdf)

- Stuart Kaye, “Freedom of Navigation, Surveillance and Security: Legal Issues Surrounding the Collection of Intelligence from Beyond the Littoral”, 24 Australian Year Book of International Law 93 (2005). [hereinafter Stuart Kaye, “Freedom of Navigation, Surveillance and Security”] (available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/AUYrBkIntLaw/2005/7.html#_Ref79163184)

- Stuart Kaye, “Freedom of Navigation, Surveillance and Security”.

- Stuart Kaye, “Freedom of Navigation, Surveillance and Security”; See also Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, The Commander’s Handbook of the Law of Naval Operations, “General Maritime Regimes Under Customary International Law as Reflected in the 1982 LOS Convention,” 2-12. (available at: http://www.jag.navy.mil/documents/NWP_1-14M_Commanders_Handbook.pdf )

- Raul Pedrozo, “Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone: East Asia Focus”, 90 Int’l L. Stud. 514, 525 at note 29, (2014). [hereinafter Raul Pedrozo, Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone] (available at: https://www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/973bec67-9225-4dde-9550-26279c600e2f/Military-Activities-in-the-Exclusive-Economic-Zone.aspx)

- Raul Pedrozo, “Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone”, 525-526. 13

- Raul Pedrozo, “Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone”, 539.

- Raul Pedrozo, “Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone”, 539. 15

- Raul Pedrozo, “Military Activities in the Exclusive Economic Zone”, 524. 16

- Stuart Kaye, “Freedom of Navigation, Surveillance and Security.”

- Robert Burns and Lolita C. Baldor, Pentagon Cites “Dangerous” Chinese Jet Intercept, The Associated Press (Aug. 22, 2014) (available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/pentagon-cites-dangerous-chinese-jet-intercept).

- See generally Reuters, “U.S. Accuses China of Dangerous, High-speed Intercept Of Spy Plane In South China Sea”, Reuters (Jun. 7, 2016). (available at: http://www.newsweek.com/china-spy-plane-intercept-unsafe-south-china-sea-united-states-high-speed-asia-467714)

- Ryan Browne, “U.S. Chinese and U.S. aircraft in ‘unsafe’ encounter”, CNN (Feb. 10, 2017) (available at: http://edition.cnn.com/2017/02/09/politics/us-china-aircraft-unsafe-encounter/index.html).