Chapter 3: Freedom of Navigation

Freedom of Navigation

“Upon our naval and air patrol . . . falls the duty of maintaining the American policy of freedom of the seas, now.”1

– President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Fireside Chat, September 11, 1941

“As we go forward, the United States will continue to fly, sail, and operate wherever international law allows, and we will support the right of all countries to do the same.”2

– President Barack H. Obama, Address to the People of Vietnam, May 24, 2016

Introduction

This chapter focuses on the application of the broad principles of freedom of the high seas and navigation rights, as outlined in the LOSC, within specific situations that permit coastal States to impose some limitations on freedom of navigation including “innocent passage” and “transit passage.”3 These rights are critical to U.S. commerce and military operations central to U.S. national security interests. The U.S. is not a party to the LOSC, but it considers the provisions of the Convention relating to the high seas and navigation rights to be a reflection of the customary international law that is binding on all States.

This chapter analyzes the legal definition of innocent passage by vessels through territorial waters and discusses the relevant articles of the LOSC regarding innocent passage. It then outlines the legal definition of transit passage through international straits and discusses the relevant articles of the LOSC regarding transit passage. The right of archipelagic sea lanes passage for ships and aircraft is also part of the freedom of navigation framework within the LOSC, but it will not be addressed in depth here.4 The final section highlights the U.S. Freedom of Navigation Program, which is designed to challenge unlawful limitations imposed by coastal States in some of the most hotly contested waters around the globe.

Right of Innocent Passage

The right of innocent passage for foreign vessels within the territorial sea of a coastal State is defined as “navigation through the territorial sea for the purpose of (a) traversing that sea without entering internal waters or calling at a roadstead or port facility outside internal waters; or (b) proceeding to or from internal waters or a call at such roadstead or port facility.” Passage must be “continuous and expeditious,” but it may include stopping and anchoring when incidental to ordinary navigation or rendered necessary by unusual circumstances.5

Article 19 of the LOSC declares that passage is “innocent” so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace, good order, or security of the coastal State and further outlines a list of 12 activities that are considered “prejudicial.” This list effectively precludes a range of military operations, including practicing or exercising weapons; collecting information to the prejudice of the coastal State; launching, landing or taking on board any aircraft or military device; and jamming coastal State communications. Submarines and underwater vehicles conducting innocent passage must navigate on the surface and show their flag.6 It is important to note that the right of innocent passage only applies to foreign vessels. Aircraft in flight are not entitled to innocent passage and thus aircraft must remain onboard vessels during innocent passage.7

An exception to the authority to deny innocent passage to aircraft exists within the limited context of the “right of assistance entry”8 based on the long-recognized duty of mariners to render immediate rescue assistance to those in danger or distress at sea. The right of assistance entry permits entry into the territorial sea by ships or, under certain circumstances, aircraft without permission of the coastal State for the limited purposes of rescue or assistance. This principle of customary international law is also reflected in the “duty to render assistance” described in Article 98 of the LOSC.9

The right of innocent passage applies to straits used for international navigation in accordance with the LOSC and cannot be suspended even when a situation of armed conflict exists.10 The right of innocent passage also applies to archipelagic waters, but it can be subject to temporary published suspensions for the protection of coastal State security.11

Lawful Limitations on Innocent Passage

Laws and Regulations of the Coastal State Relating to Innocent Passage

Article 24 prohibits coastal States from hampering the innocent passage of foreign ships through the territorial sea unless specifically authorized by other Articles of the LOSC. Coastal States are also prohibited from discriminating among States or cargoes from different nations.12 However, the LOSC permit coastal States to adopt laws

and regulations related to passage through the territorial sea in the following list of circumstances:

- The safety of navigation and the regulation of maritime traffic;

- The protection of navigational aids and facilities and other facilities or installations;

- The protection of cables and pipelines;

- The conservation of the living resources of the sea;

- The prevention of infringement of the fisheries laws and regulations of the coastal State;

- The preservation of the environment of the coastal State and the prevention, reduction and control of pollution thereof;

- Marine scientific research and hydrographic surveys;

- The prevention of infringement of the customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations of the coastal State;

***

- Prevention of collisions at sea including the use of designated sea lanes and traffic separation schemes; and

***

- Require foreign nuclear-powered ships and ships carrying nuclear or other inherently dangerous or noxious substances to carry documents and observe special precautionary measures established for such ships by international agreements.13

Despite the broad regulatory authority outlined above, Article 26 of the LOSC prohibits the imposition of charges levied upon foreign ships for innocent passage unless a ship receives services rendered by the coastal State for which payment is due, such as refueling or maintenance.

Rights of Protection of the Coastal State

A coastal State may take necessary steps in its territorial sea to prevent passage which is not innocent and may announce temporary suspensions of innocent passage through a required public notice if the suspension is essential for security reasons, which include weapons exercises.14 While the text of the relevant articles of the LOSC does not explicitly grant the right of innocent passage to warships, the overall language of the LOSC in the context of its negotiation history and customary international law all make it clear that warships enjoy the right of innocent passage on an unimpeded and unannounced basis.15 However, if a warship does not comply with coastal State regulations that conform to established principles of international law and disregards a request for compliance that is made to it, the coastal State may require the warship to leave the territorial sea immediately.16 Due to the sovereign immunity of warships (discussed further in Chapter Six: Sovereign Immunity) the degree to which a coastal State can force a warship to exit its territorial waters in this situation is not clear. Additionally, coastal States may not prohibit transit or otherwise impair the rights of innocent passage of nuclear-powered sovereign vessels.17

Differing Interpretations Regarding Innocent Passage

Several articles of the LOSC addressing innocent passage have led to differing interpretations by States. For example, some coastal States interpret Article 19(1), which allows for innocent passage, to prohibit several activities not explicitly listed under Article 19(2). Another issue of interpretation is whether the coastal State may require foreign ships conducting innocent passage to carry equipment that enables the coastal State to monitor the ship’s movement. Some commentators have argued that no LOSC provision prevents the coastal State from imposing such a measure.18 However, the LOSC does not expressly characterize a foreign ship’s passage in the territorial sea as non-innocent if it fails to enable monitoring by the coastal State.

These disputed issues originate from the negotiations that preceded the adoption of the LOSC, which placed the interests of maritime powers in conflict with those of coastal States. Maritime powers pushed for more freedom of navigation, but coastal States argued for the ability to constrain mobility in certain circumstances to protect coastal State interests.19

Unlawful Restrictions Claimed by Outlier States

A number of States unlawfully require prior notification before a foreign warship may conduct innocent passage through their territorial waters, but most of these States do not specify when the foreign warship must provide the notification. A larger number of States, notably including China, not only unlawfully require notification, but also require that prior permission be granted.

Saudi Arabia unlawfully asserts that innocent passage does not apply to its territorial sea where there is an alternate route through the high seas or an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) which is equally suitable.

Romania20 and Lithuania21 prohibit the passage of ships carrying nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction through their territorial seas.

A complete list of the unlawful restrictions imposed by coastal States upon the right of innocent passage can be found in the Maritime Claims Reference Manual (MCRM) issued by the Department of Defense (DoD) Representative for Ocean Policy Affairs (REPOPA) published here.

Right of Transit Passage

The right of transit passage is defined as the exercise of the freedoms of navigation and overflight, solely for the purpose of continuous and expeditious transit through an international strait between one part of the high seas or an EEZ and another part of the high seas or an EEZ, in the normal modes of operation utilized by ships and aircraft for such passage. An exception to the right of transit passage declares that the right “shall not apply if the strait is formed by an island of a State bordering the strait and its mainland” and “there exists seaward of the island a route through the high seas or through an exclusive economic zone of similar convenience with respect to navigational and hydrographical characteristics.”22 Transit passage cannot be hampered or suspended by the coastal State for any purpose during peacetime. This also applies to transiting ships, including warships, of States at peace with the bordering coastal State but involved in armed conflict with another State.23 The right of transit passage applicable in peacetime, along with the laws and regulations of States bordering straits adopted in accordance with international law, continue to apply during armed conflict. However, during transit belligerents must not conduct offensive operations against enemy forces, nor use such neutral waters as a place of sanctuary or as a base of operations.24

It is important to note a few key differences between innocent passage and transit passage that are particularly relevant to military operations and to highlight the fact that fewer restrictions may be imposed on transit passage when compared to innocent passage. While there is no right to innocent passage for aircraft, and coastal States may deny entry to aircraft attempting to traverse airspace over their territorial waters, they may not deny transit passage to aircraft over an international strait.

In addition, while coastal States may require submarines to conduct innocent passage on the surface and showing their flag, they may not prohibit submarines from conducting transit passage submerged.25 Another difference is that transit passage may not be suspended by the coastal State, whereas innocent passage may be temporarily suspended.26

Duties of Ships and Aircraft During Transit Passage

Ships and aircraft exercising the right of transit passage shall (a) proceed without delay through or over the strait; (b) refrain from any threat or use of force against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of States bordering the strait; and (c) refrain from any activities other than those incident to their normal modes of continuous and expeditious transit unless rendered necessary by force majeure or by distress.27 Surface warships may transit in a manner consistent with sound navigational practices and the security of the force, including the use of their electronic detection and navigational devices such as radar, sonar, and depth sounding devices, formation steaming, and the launching and recovery of aircraft.28

Laws, Regulations, & Duties of States Bordering Straits Relating to Transit Passage

Foreign ships are required to obtain the authorization of the coastal States that border straits prior to carrying out any research or survey activities while exercising the right of transit passage.29 States bordering straits have the authority to establish sea lanes and traffic separation schemes where necessary to promote the safe passage of ships in straits used for international navigation.30Warships, auxiliaries, and government ships operated on exclusive government service, i.e., sovereign-immune vessels, are not legally required to comply with such sea lanes and traffic separation schemes while in transit passage, but they must exercise due regard for the safety of navigation. Coastal States may not prohibit transit or otherwise impair the right of transit passage of nuclear-powered sovereign vessels.31

Coastal States have the authority to adopt laws and regulations relating to transit passage through straits, with respect to all or any of the following:

(a) The safety of navigation and the regulation of maritime traffic, as provided in Article 41;

(b) The prevention, reduction and control of pollution, by giving effect to applicable international regulations regarding the discharge of oil, oily wastes and other noxious substances in the strait;

(c) With respect to fishing vessels, the prevention of fishing, including the stowage of fishing gear;

(d) The loading or unloading of any commodity, currency or person in contravention of the customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations of States bordering straits.32

States bordering straits have the duty not to hamper transit passage and to give appropriate publicity to any danger to navigation or overflight within or over the strait of which they have knowledge.33

U.S. Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program

To preserve the freedom of the seas, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) regularly conducts operational challenges to many of the unlawful restrictions on freedom of navigation that have been outlined above through the U.S. Freedom of Navigation (FON) program. In accordance with U.S. Oceans Policy (1983), the U.S. “will exercise and assert its rights, freedoms, and uses of the sea on a worldwide basis in a manner that is consistent with the balance of interests” reflected in the LOSC. The FON Program includes: (1) consultations, representations, and protests by U.S. diplomats with foreign governments and (2) operational activities by U.S. military forces in and above international waters. The FON Program is implemented against excessive maritime claims by coastal States in every region of the world, based upon the DoD’s global interest in freedom of navigation and access.34

Given the high level of publicity that some FON Program operations currently receive with respect to interactions with China, it is important to highlight that the FON Program is “principle-based.” FON operations are conducted with a focus on the excessive nature of maritime claims, rather than the identity of the coastal States asserting those claims. U.S. forces challenge excessive claims asserted not only by potential adversaries and competitors, but also by allies, partners, and other States. The Program includes “both FON operations (i.e., operations that have the primary purpose of challenging excessive maritime claims) and other FON-related activities (i.e., operations that have some other primary purpose, but have a secondary effect of challenging excessive claims), in order to gain efficiencies in a fiscally constrained environment.” Each year DoD publishes an annual FON Report that summarizes FON operations and other FON related activities conducted by U.S. forces, and identifies the specific coastal nations and excessive claims challenged.35

When the FON program began in 1979, U.S. military ships and aircraft were exercising their rights against excessive claims of about 35 countries at the rate of about 30 to 40 challenges annually, but by 1999 the decline in operational challenges led the Department of the Navy and the Department of Commerce (within which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration resides) to recommend an expansion of the program to “exercise openly the traditional freedoms of navigation and overflight in areas of unacceptable claims.”36 In fiscal year 2016, the DoD conducted FON operations against 22 different States, and 13 of those States were subject to multiple challenges.37

The remainder of this chapter will highlight some recent and well publicized FON operations in some of the most hotly contested waters around the globe where freedom of navigation is vital to U.S. foreign policy, commerce, and national security interests.

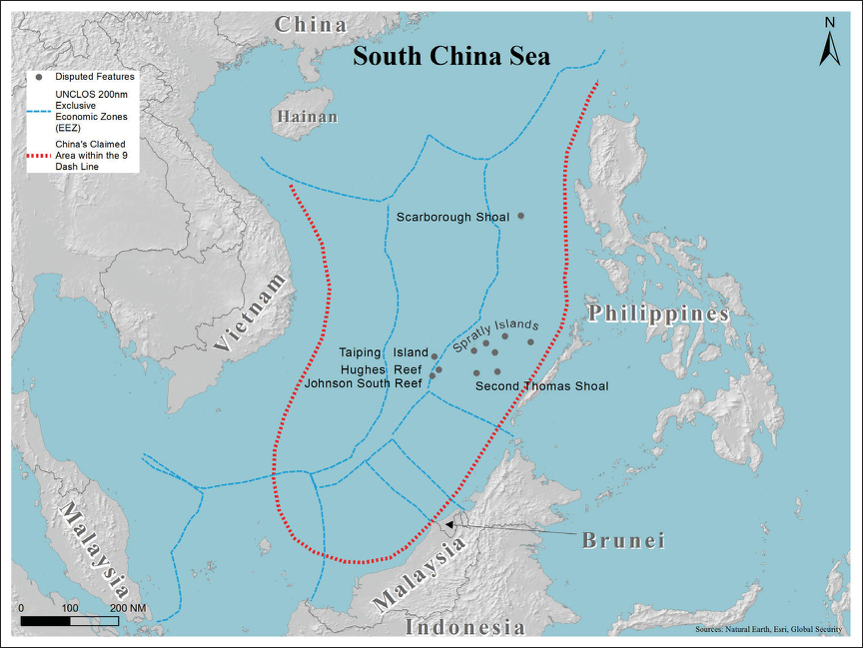

South China Sea (SCS)

The South China Sea (SCS) is the most contentious region for FON operations. China has been building artificial features and installing military equipment on them in addition to making a variety of other excessive maritime claims including broad assertions of sovereignty as exemplified by the so-called “nine dash line.” See Chapter Ten: The South China Sea Tribunal for additional information on this topic. In 2016 the U.S. challenged the following Chinese restrictions on freedom of navigation: (1) excessive straight baselines; (2) jurisdiction over airspace above the EEZ; (3) restriction on foreign aircraft flying through an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) without the intent to enter national airspace; (4) domestic law criminalizing survey activity by foreign entities in the EEZ; and (5) prior permission required for innocent passage of foreign military ships through the territorial sea.38 On December 22, 2015, the Secretary of Defense outlined the U.S. views regarding FON operations in the SCS in response to an inquiry from Senator John McCain regarding a widely discussed FON operation conducted by the USS Lassen in the South China on October 27, 2015.39 Senator McCain and other members of Congress have suggested that the DoD should more clearly articulate the particular excessive claim(s) being challenged by these types of FON operations.40 In October 2016, a U.S. Navy destroyer sailed close to Woody Island, which is also claimed by Taiwan and Vietnam, in the fourth such operation by the U.S. Navy in the year. China called the act “provocative” and has responded to U.S. FON operations in the SCS with a wide variety of claims that lack support under the LOSC.41

Arabian Gulf & Strait of Hormuz

On January 12, 2016, Iran detained nine U.S. sailors and a naval officer near Farsi Island in the Arabian Gulf and ransacked two U.S. vessels. The sailors were carrying out innocent passage when one of their boats suffered an engine problem, and thus the detention and search of the vessels was in violation of international law.42 Iran was also subject to FON operations in both 2015 and 2016 because it imposed restrictions on the right of transit passage through the Strait of Hormuz and attempted to prohibit foreign military activities and practices in the EEZ.43

Tensions have continued in the Strait of Hormuz in 2016. On January 8, the USS Mahan (DDG-72) was escorting a Navy oiler and the USS Makin Island (LHD-8) when four Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy fast inshore attack craft, with crew-served weapons manned, approached within 900 yards of the guided missile destroyer. After the Iranian boats failed to respond to a radio call and flares signaling them to stop, sailors on board the U.S.S. Mahan fired warning shots with a .50-caliber machine gun and a Navy helicopter also deployed a smoke screen generator. These actions caused the Iranian boats to halt their high-speed approach and observe the U.S. vessels complete the transit passage. There were 35 close encounters between U.S. and Iranian vessels in 2016, most of which occurred during the first half of the year, and 23 encounters in 2015.44

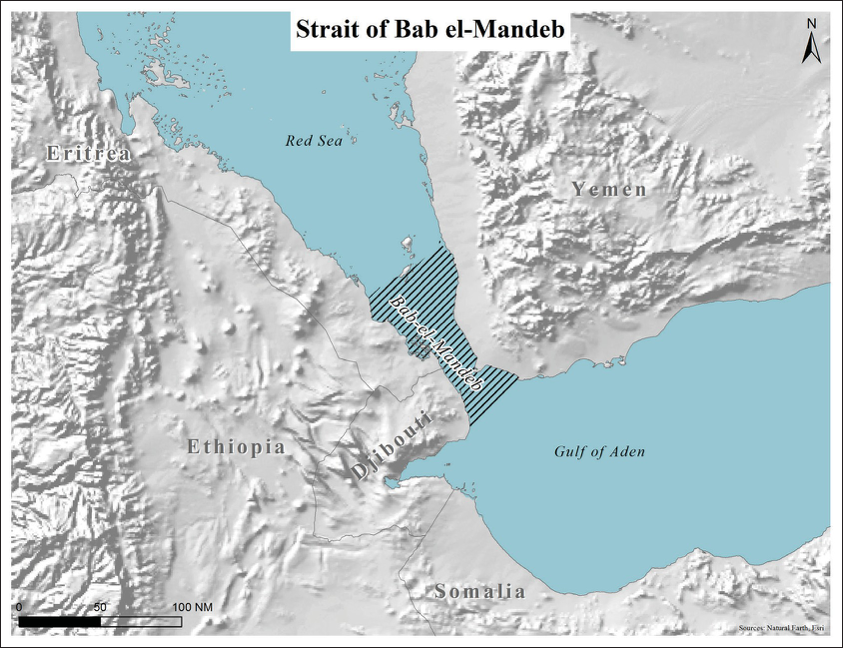

Bab el-Mandeb

On October 12, 2016, the sixteenth anniversary of the bombing of the USS Cole (DDG- 67) in Aden, Yemen, Houthi rebels in Yemen launched missiles at U.S. Navy ships operating near the Bab el Mandeb international strait for the second time in that week. The U.S. responded with Tomahawk cruise missile strikes to destroy three coastal radar sites in Houthi-controlled territory on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast. Pentagon press secretary Peter Cook stated that the U.S. will “respond to any further threat to our ships and commercial traffic, as appropriate, and will continue to maintain our freedom of navigation in the Red Sea, the Bab al-Mandeb and elsewhere around the world.” 45

Conclusion

The FON Program presents a balancing of diplomatic costs and benefits with the risks inherent in physical challenges. In some cases, the costs, disadvantages, or risks that come with physically challenging excessive claims might be greater than the benefits. Of course, coastal States understand this calculus and may try to use it to their advantage since they have an incentive to compel the international community to acquiesce to their excessive maritime claims.46 Continued investments in the FON Program, including diplomatic protests against unlawful claims and continued FON operations to challenge those claims, are essential to preserve key navigational rights embodied in the LOSC and customary international law. The U.S. has encouraged allies like Japan, South Korea, and Australia to join the FON Program, but they have been reluctant to conduct operations so far. The U.S. should continue to pursue this goal because the message delivered by FON operations will be stronger when more States send it.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat,” September 11, 1941, The American Presidency Project. (available at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=16012).

- Barack H. Obama, “Address to the People of Vietnam,” May 24, 2016, Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. (available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/05/24/remarks-president-obama-address-people-vietnam)

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Articles 87, 90, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397 [hereinafter LOSC]. (available at: http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part2.htm).

- LOSC, Articles 53-54.

- LOSC, Articles 17-18.

- LOSC, Articles 19-20.

- Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, The Commander’s Handbook of the Law of Naval Operations, “General Maritime Regimes Under Customary International Law as Reflected in the 1982 LOS Convention,” 2-4. [hereinafter Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M] (available at: http://www.jag.navy.mil/documents/NWP_1-14M_Commanders_Handbook.pdf).

- Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 2410.01D, “Guidance for the Exercise of Right-of-Assistance Entry”, August 31, 2010. (available at: http://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Library/Instructions/2410_01.pdf?ver=2016-02-05-175013-783); See also San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea, Articles 31-33, June, 12 1994. [hereinafter San Remo Manual] (available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/560).

- LOSC, Article 98.

- LOSC, Article 45; see also San Remo Manual, Articles 31-33. 11

- LOSC, Articles 52-53.

- LOSC, Article 24.

- LOSC, Articles 21-23.

- LOSC, Article 25.

- Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, 2-5.

- LOSC, Article 30.

- Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, 2-5.

- See John A. Knauss & Lewis M. Alexander, “The Ability and Right of Coastal States to Monitor Ship Movement: A Note”, 31 Ocean Dev. & Int’l L. 377, 379 (2000).

- See generally William Agyebeng, “Theory in Search of Practice: The Right of Innocent Passage in the Territorial Sea”, Cornell International Law Journal, Volume 39, Issue 2, 389-390, (2006). (available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1672&context=cilj)

- “Romania: Act Concerning the Legal Regime of Internal Waters, the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone of Romania” (Aug. 7, 1990), 19 L. Seas Bull. 9, 11 (1991).

- Lithuania: Legislation on the Territorial Sea, 25 L. Seas Bull. 75 (1994).

- LOSC, Article 38.

- Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, 2-6; See also San Remo Manual, Articles 31-33, June, 12 1994.

- San Remo Manual, Articles 27-30.

- Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, 2-6.

- LOSC, Article 25.

- LOSC, Article 39.

- Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, 2-6.

- LOSC, Article 40.

- LOSC, Article 41.

- Naval Warfare Publication 1-14M, 2-5, 2-6.

- LOSC, Article 42.

- LOSC, Article 44.

- See generally DoD Freedom of Navigation Fact Sheet, March 2015 [hereinafter DoD Freedom of Navigation Fact Sheet] (available at: http://policy.defense.gov/Portals/11/Documents/gsa/cwmd/DoD%20FON%20Program%20–%20Fact%20Sheet%20%28March%202015%29.pdf)

- See generally DoD Freedom of Navigation Fact Sheet.

- James Kraska, “The Law Of The Sea Convention: A National Security Success – Global Strategic Mobility Through The Rule Of Law”, 544 The Geo. Wash. Int’l L. Rev. 39, 569, (2008). (available at: http://www.virginia.edu/colp/pdf/kraska-los-national-security-success.pdf )

- U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) Freedom of Navigation (FON) Report for Fiscal Year (FY) 2016. [hereinafter DoD FON Report for FY 2016] (available at: http://policy.defense.gov/Portals/11/FY16%20DOD%20FON%20Report.pdf )

- DoD FON Report for FY 2016.

- “Letter from Secretary of Defense Ash Carter to Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) regarding U.S. military operations in the South China Sea”, Dec. 22, 2015. (available at: https://news.usni.org/2016/01/05/document-secdef-carter-letter-to-mccain-on-south-china-sea-freedom-of-navigation-operation).

- Lynn Kuok, “The U.S. FON Program in the South China Sea: A lawful and necessary response to China’s strategic ambiguity”, Brookings, June 2016 (available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/The-US-FON-Program-in-the-South-China-Sea.pdf).

- Lucas Tomlinson, “China flies nuclear-capable bomber in South China Sea after Trump Taiwan call, US officials say”, Fox News (Dec. 9, 2016). (available at: http://www.foxnews.com/world/2016/12/09/china-flies-nuclear-capable-bomber-in-south-china-sea-after-trump-taiwan-call-us-officials-say.html?refresh=true)

- Dan Lamothe, Navy: “‘Poorly led and unprepared’ sailors were detained by Iran after multiple errors”, Washington Post, June 30, 2016. (available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2016/06/30/navy-poorly-led-and-unprepared-sailors-were-detained-by-iran-after-multiple-errors).

- DoD FON Report for FY 2016.

- See generally Michael Gordon, “American Destroyer Fires Warning Shots at Iranian Boats”, N.Y. Times, Jan. 9, 2017. (available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/09/world/middleeast/iran-uss-mahan-shots.html?_r=0)

- See generally Lolita C. Baldor, “US strikes in Yemen risk wider entanglement in civil war”, Associated Press, Oct. 13, 2016, (available at: http://www.apnewsarchive.com/2016/Officials_say_US_missiles_destroy_radar_sites_on_Yemen_coast/id-f03b50ff873a471c88ebb1538c1e3dc9)

- James Kraska, “The Law Of The Sea Convention: A National Security Success – Global Strategic Mobility Through The Rule Of Law”, 544 The Geo. Wash. Int’l L. Rev. 39, 571, (2008).