Chapter 10: The South China Sea Tribunal

The South China Sea Tribunal

Background

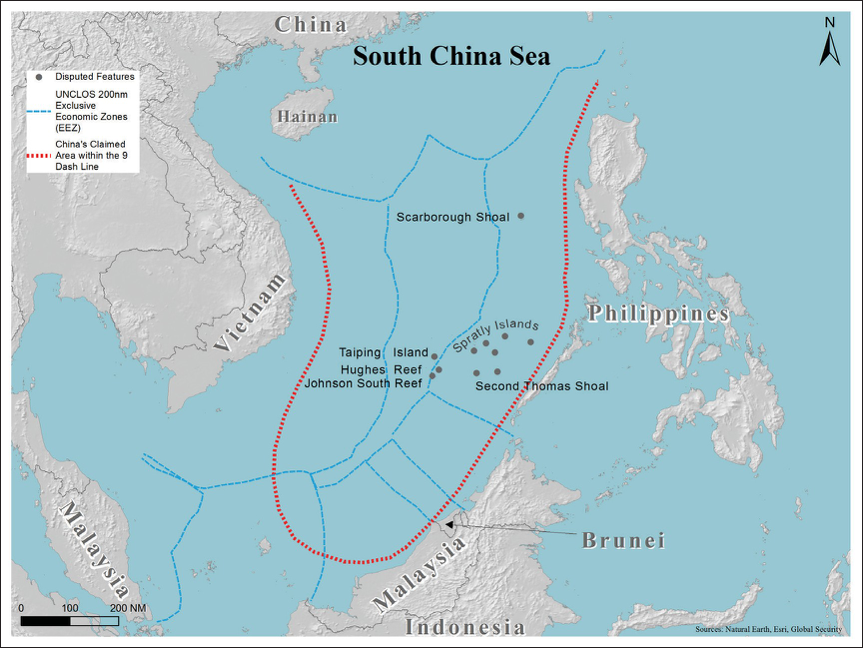

The increasing risk of conflict in the South China Sea (SCS) poses a significant threat to stability in the region and to U.S. interests. Not only do Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines have competing territorial and jurisdictional claims over the physical features of the SCS, but U.S. Freedom of Navigation (FON) operations have also elicited an increasingly hostile tone from Beijing. See Chapter Three: Freedom of Navigation, for additional information about this topic. Additionally, Beijing’s insistence that it has “indisputable sovereignty over the South China Sea Islands and the adjacent waters” within the so-called “nine-dash line” as well as its accelerated industrial scale “island building” for military purposes have increased the overall international tension in this region. China’s militarization of the SCS is of great concern to the U.S. and its regional allies because China’s aggressive assertions serve to destabilize the region and weaken important international agreements such as the LOSC. Additional concerns include China’s refusal to arbitrate legitimate disputes concerning the law of the sea, an aversion to multilateral negotiations, and the refusal to enter into bilateral negotiations on the basis of equality.

The South China Sea (SCS) Tribunal

The South China Sea (SCS) Tribunal (the Tribunal) established through the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) under the terms of Part XV of the LOSC resulted from the efforts of the Philippines to hold China accountable for their activities near the Scarborough Shoal, the claims and conduct of China in the Spratly Islands, and Chinese assertion of sovereignty over wide areas of the SCS, including parts of the EEZ of the Philippines. The Philippines alleged that China violated its rights and privileges enshrined within the LOSC, and on July 12, 2016 the Philippines received a favorable decision from the Tribunal. The Tribunal ruled overwhelmingly in favor of the Philippines’ claims, although it declined to hold that China had behaved in bad faith or to impose special enforcement remedies.

History of SCS Disputes

The SCS has not always been a tense geopolitical area. At the end of World War II, none of the neighboring states occupied a single island in the entire SCS. However, over the next fifty years, there would be periodic escalations and de-escalations in the SCS such that no country can claim consistent possession of the islands there. Between 1946 and 1947, China began the process of establishing itself in the Spratly Islands, Woody Island, and the Paracel Islands, while the French and Vietnamese established themselves on Pattle Island. During China’s civil war, the islands then occupied by China were again vacated. After this period, neighboring countries again began making claims on islands. In 1974, China engaged South Vietnam in the Battle of the Paracel Islands to wrest control of the islands. Then in 1988, China moved into the Spratly Islands and defeated Vietnam’s opposition to occupy the Johnson Reef. Tensions again escalated in 1995 when China built bunkers above Mischief Reef following the grant of a Philippine oil concession.

2002 was a year which offered great hope for a breakthrough in the SCS. China deviated from its long tradition of bilateral negotiations and instead worked with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to create the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the SCS.

In this declaration, the parties promised “to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, among others, refraining from action of inhabiting the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features and to handle their differences in a constructive manner.”A

A period of reduced tensions followed in the SCS, although tensions in the East China Sea between Japan and China continued during this time. The latest round of tensions commenced in May 2009 when Malaysia and Vietnam sent a joint submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to state their claims. China was among those countries that responded and submitted a controversial map to the UN Secretary General containing the “nine-dash” line.

In submitting the “nine-dash” line in 2009, China asserted that it has “indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof.”1 This statement could either be construed as: 1) China claims all of the territory in the SCS with adjacent waters allowed under international law, or 2) China claims all land and water features enclosed by the line beyond what is accepted under international law. The line runs along the coast of Vietnam all the way down to the coast of Malaysia and Brunei and back up to the Philippines.

Following publication of the map, China and the Philippines engaged in a standoff at the Scarborough Shoal in 2012. A Philippine Navy surveillance aircraft detected eight Chinese fishing vessels near the Scarborough Shoal on April 8, 2012. After finding endangered clams, coral, and live sharks on the vessels, in violation of Philippine law, the Philippines deployed the military vessel BRP Gregorio del Pilar to arrest the fishermen. In response, China dispatched maritime vessels to prevent the Philippines from detaining the fishermen and had People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) vessels in the area on standby. Concurrent with this incident, both countries engaged in non-military retaliations. China imposed restrictions on banana imports from the Philippines, and the Philippines imposed restrictions on Chinese tourism in the Philippines. By July 2012, China effectively blocked access to the Scarborough Shoal by Filipino fisherman.

Matters Adjudicated by the Tribunal

On January 22, 2013, the Philippines initiated arbitral proceedings against China under Articles 286 and 287 of LOSC.2 Article 286 allows for the referral of disputes, where no settlement has been reached, to binding resolution in a court or tribunal specified in Article 287. Through Article 287, the Philippines elected to use an arbitral tribunal in accordance with Annex VII of the LOSC. See Chapter Nine: LOSC Dispute Resolution Provisions, for additional information about that section of the LOSC. In July 2013, the Tribunal appointed the PCA to serve as Registry for the proceedings. The PCA is an intergovernmental organization established by the 1899 Hague Convention on the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes.

Relief Sought By The Philippines

In its request to initiate the proceedings, the Philippines sought an award that:

- declares that the LOSC governs the rights and obligations of the parties with regard to the waters, seabeds, and maritime features of the SCS such that China’s “nine-dash line” is invalid;

- determines under Article 121 of the LOSC whether certain maritime features claimed by both China and the Philippines are islands, low tide elevations, or submerged banks, and whether they are capable of generating entitlement to maritime zones greater than 12 nautical miles; and

- declares that China has unlawfully exploited the living and non-living resources in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, and has unlawfully prevented the Philippines from exploiting the living and non-living resources therein, and enables the Philippines to enjoy and exercise the rights within and beyond its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.

In subsequent submissions to the Tribunal, the Philippines asserted two additional claims of LOSC violations against China. The first additional claim alleged China’s breach of obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment under Article 192, through its harvesting of endangered species and coral as well as through the construction of artificial features. The second claim was that Chinese government vessels were operating to impair the navigation of Philippine vessels in a manner inconsistent with safe navigation under the LOSC.

China’s Response

On February 19, 2013, China rejected the arbitration through a diplomatic note to the Philippines. China noted “the two countries have overlapping jurisdictional claims over parts of the maritime area in the SCS and that both sides had agreed to settle the dispute through bilateral negotiations and friendly consultation.”3 Throughout the proceedings China did not appear nor participate, but the Philippines was able to successfully invoke Article 9 of Annex VII of the LOSC to request that the proceeding continue despite China’s non-participation. On October 29, 2015, the Tribunal determined unanimously that it had jurisdiction over the SCS matters and that China’s refusal to participate in the proceedings did not deprive the Tribunal of jurisdiction.B China reacted with a statement from its Ministry of Foreign Affairs claiming that there would be no binding effect on China. China asserted that the claims presented to the Tribunal were a political provocation under the cloak of law and that China has indisputable sovereignty over the SCS Islands and the adjacent waters. China also claimed that its sovereignty and relevant rights in the SCS were formed through the course of history and asserted by successive Chinese governments, through China’s domestic laws, and protected under international law including the LOSC. With regard to the issues of territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests, China asserted that it would not accept any outcome imposed on it or any unilateral resort to a third-party dispute settlement.4 The Tribunal issued its decisions on July 12, 2016.

The Decisions of the Tribunal

Matter 1: Historic Rights and the Nine-Dash Line

Although the Tribunal did not rule on any question of sovereignty over land territory and did not delimit any boundary between the parties, the Tribunal concluded that: (a) there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the islands and waters of the SCS; and, regardless, (b) any pre-existing, historic Chinese rights were extinguished to the extent they were incompatible with the LOSC. Therefore, the Tribunal concluded that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the nine-dash line.5

Matter 2: Status of Features

The Tribunal also evaluated whether certain reefs being claimed by China were above high tide, as features above water at high tide generate at least a 12 nautical mile territorial sea. Features below water at high tide do not generate such an entitlement, even if such features have been modified by land reclamation and construction. As for the features which the Tribunal found to be high-tide elevations, the Tribunal considered whether any of these could generate maritime zones of 200 nautical miles and a continental shelf, or whether these features were just rocks which could not sustain human habitation or economic life and thus only generated rights to a territorial sea. The Tribunal noted that to qualify as islands that generate an EEZ, maritime features must be able to either sustain a stable human community or economic life that does not depend on outside resources and is not purely extractive in nature. Evaluation of features must be made in their natural state, without taking into account artificial enlargements or enhancements like those undertaken by the Chinese. The Tribunal found that only small groups of transient fisherman historically used the Spratly Islands and that their economic activities had only been extractive. Thus, the Tribunal determined that none of the Spratly Islands could generate extended maritime zones. In short, China could not claim an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) based on its claims upon the Spratly Islands.6

The Tribunal’s statement as to the status of features in the SCS has limited the scope of maritime entitlements that China could claim and applies also to other States and their claims in the SCS. The Tribunal’s designation of the Johnson South Reef, Hughes Reef, and the Scarborough Shoal as “rocks” instead of “islands,” not only limits Chinese claims and maritime entitlements, but also provides guidance on how similar

cases involving other States could be adjudicated in the future. Such a characterization could be applied to other locations of geopolitical interest where the status of features might be contested. An example of this could be the status of certain U.S. possessions in the Pacific Ocean, such as Howland Island.

Matter 3: Lawfulness of Chinese Actions

The Tribunal found that certain areas were within the EEZ of the Philippines, and, moreover, that China had violated certain sovereign rights of the Philippines in its EEZ. Such violations included: (1) interfering with Philippine fishing and petroleum exploration, (2) failing to prevent Chinese fisherman from fishing in the EEZ, and (3) constructing artificial islands. The Tribunal also determined that China unlawfully restricted the traditional fishing rights of Philippine fishermen at Scarborough Shoal and that China’s law enforcement vessels unlawfully created a serious risk of collision when they physically obstructed Philippine vessels.C

Matter 4: Harm to Marine Environment

The Tribunal concluded that China violated its obligation to preserve and protect fragile ecosystems and habitat of depleted, threatened, or endangered species through both its harmful fishing practices and its large-scale land-reclamation activities and construction of artificial features. The Tribunal further noted that China’s failure to make available any meaningful evaluation of the environmental impact created by its land-reclamation activities violated the LOSC. The Tribunal also held that China failed to prevent its fishermen from harvesting endangered sea turtles, coral, and giant clams on a substantial scale.7

Matter 5: Aggravation of Dispute

The Tribunal also considered whether China’s actions aggravated the dispute between the parties after the arbitration had commenced. Although the Tribunal concluded that China’s continuation of the large-scale land reclamation and construction of artificial islands was incompatible with the obligations on a State during dispute resolution proceedings, the Tribunal found that it lacked jurisdiction to consider implications of a stand-off between Philippine marines and the Chinese naval and law enforcement vessels at Second Thomas Shoal. Disputes involving military activities are excluded from compulsory settlement under the LOSC.8

Impact of the Tribunal Decisions

Although the decisions of the Tribunal could be perceived as a huge win for the Philippines, as well as a victory for the notion of peaceful dispute resolution, its enforceability remains an open question. The decision is final and binding pursuant to Articles 11 and 296 of the LOSC, to which China is a party. Despite this, as recently as late October 2016, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has stated that the situation at the disputed Scarborough Shoal in the SCS “has not changed and will not change.”9 It currently remains unclear whether China will comply and whether the Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte will use the Tribunal’s decisions as leverage to influence relations between the two countries.10 So far, President Duterte has threatened to challenge Beijing if they begin extracting gas within the EEZ of the Philippines in the SCS. However, he has also indicated a willingness to set the Tribunal decision aside to facilitate better relations with China. China has taken limited steps to ease tensions by permitting some access to the Scarborough Shoal for Filipino fishermen, while retaining overall control of access.

Beyond China, the Philippines, and the U.S., other claimants in the SCS have welcomed the refutation of China’s “nine-dash line.” Vietnamese authorities have refused to recognize Chinese passports that feature the nine-dash line to symbolically deny recognition of China’s claim.11 Separately, Taiwan actually supports the legitimacy of China’s “nine-dash line” claim because it also supports Taiwan’s claim to Taiping Island, the largest of the Spratly Islands. By characterizing Taiping Island as a “rock” instead of an “island,” the Tribunal denied Taiwan a 200 nautical mile EEZ.12 The principles applied by the Tribunal, if adopted by others, could, as noted above, call into question maritime zones claimed by other nations (including the U.S. and France) by virtue of small and uninhabited islands.

What the Tribunal decision could not do, however, is resolve tensions in the SCS. The Tribunal could only interpret the LOSC and determine the kinds of maritime zones that could be lawfully claimed. It lacked jurisdiction to adjudicate claims between China and other States concerning sovereignty. Given China’s current approach, it does not seem that tensions in the SCS will subside at any time in the near future.

- “DECLARATION ON THE CONDUCT OF PARTIES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA.” Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Accessed July 06, 2017, (available at http://asean.org/?static_post=declaration-on-the-conduct-of-parties-in-the-south-china-sea-2).

- People’s Republic of China, Note Verbale CML/18/2009 (May 7, 2009).

- Press Release, Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Arbitration Between the Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China (July 13, 2015), (available at http://archive.pca-cpa.org/shownewsa454.html?nws_id=518&pag_id=1261&ac=view).

- Hong Lei, “Statement of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China Spokesperson”, February 19, 2013, (available at http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2511_665403/t1015317.shtml).

- Phil. V. China, PCA No. 2013-19 at ¶ 413, Award of October 29, 2015.

- Phil. v. China, PCA Case No. 2013-19, Award of July 12, 2016.

- Phil. v. China, PCA Case No. 2013-19 at ¶ 230-278, Award of July 12, 2016.

- Phil. v. China, PCA Case No. 2013-19 at ¶ 539-551, 615-626, Award of July 12, 2016.

- Phil. V. China, PCA No. 2013-19 at ¶ 716, 757, 814, and 993, Award of October 29, 2015.

- Phil. v. China, PCA Case No. 2013-19 at ¶ 950-966, Award of July 12, 2016.

- Phil. v. China, PCA Case No. 2013-19 at ¶ 1161-1162, 1163-1181, Award of July 12, 2016, (regarding military activities and reclamation and construction activities).

- Paul Carsten & Manuel Mogato, “China Says ‘Situation’ at Disputed Scarborough Shoal has not Changed”, Reuters, Oct. 31, 2016, (available at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-china-philippines-idUSKBN12V0YT).

- Nandini Krishnamoorthy, “Duterte Says He Will Insist on International Tribunal Ruling if China Drills in South China Sea”, International Business Times, Dec. 29, 2016, (available at http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/duterte-says-he-will-insist-international-tribunal-ruling-if-china-drills-south-china-sea-1598539).

- “South China Sea: Vietnam Airport Screens Hacked”, BBC News, July 29, 2016, (available at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36927674).

- Austin Ramzy, Taiwan, “After Rejecting South China Sea Decision, Sends Patrol Ship”, N.Y. Times, July 13, 2016, (available at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/14/world/asia/south-china-sea-taiwan.html).A. “DECLARATION ON THE CONDUCT OF PARTIES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA.” Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Accessed July 06, 2017, (available at http://asean.org/?static_post=declaration-on-the-conduct-of-parties-in-the-south-china-sea-2).

B. Phil. V. China, PCA No. 2013-19 at ¶ 413, Award of October 29, 2015.

C. Phil. V. China, PCA No. 2013-19 at ¶ 716, 757, 814, and 993, Award of October 29, 2015.