The JFK Library: A Man and His Children

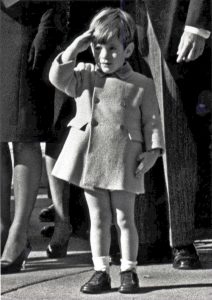

It’s an image etched into our national consciousness as Americans, perhaps from before we even know its context: that of a toddler John F. Kennedy, Jr. saluting his father’s casket. It was November 25th, 1963, making it the little boy’s third birthday, and while standing beside his grieving mother and sister he raised his right hand and made the gesture that has since become an inseparable part of American collective memory.

Perhaps, like me, you’ve been simultaneously entranced and haunted by the moment since childhood. My mom has loved studying Kennedy history since she was a teenager, so I don’t remember a time when I was not acutely aware of such images of their famous political family — the joyous and the triumphant, the solemn and the heartbreaking. Yet John Jr.’s innocent, imitative expression of respect at his father’s funeral has always been, by far, the most powerful to me.

At the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts, the untimely loss of the thirty-fifth president of the United States is not dwelled upon: one hallway, set apart from all other galleries with its stark black walls, features a handful of monitors that play news footage of the funeral, and that is the extent of it. After all, this is the part of the story everyone already knows with painful intimacy.

Instead, the museum makes its mission to “engage with citizens of all ages and nationalities through JFK’s life story and the ideals he championed,” and it certainly accomplishes this. I visited with my sister last weekend, and we were deeply struck by the careful detail in which the library leads visitors through Kennedy’s campaign, his actions as president, and his continuing legacy to our present day. His wife Jacqueline is recognized for her work as First Lady and her efforts in historical preservation; his brother Bobby’s role as Attorney General and his sister Eunice’s advocacy for intellectually disabled individuals are highlighted; and a whole cast of international leaders like Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union, Félix and Marie-Thérèse Houphouët-Boigny of Ivory Coast, and Charles de Gaulle of France (to name just a few!) illustrate the complex political climate of the early 1960s. The library’s location, overlooking “the sea that he loved and the city that launched him into greatness,” helps to complete the picture of JFK and his world.

And then, of course, there are his children. When the Kennedys moved into the White House, they brought with them the first youngsters to live at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue since the Theodore Roosevelt administration. Caroline, just 3, and John Jr., two months old, became instant icons of pop culture, absolutely captivating the American public with their every step, babble, and baby tooth.

There is a gallery dedicated to JFK as a family man in the library’s permanent collection, but in August of last year, a temporary exhibit examining Caroline and John Jr.’s celebrity status opened in the special exhibition gallery. Titled “First Children: Caroline and John Jr. in the Kennedy White House,” it was, perhaps, my favorite part of the experience this visit.

Revealing their mother’s determination to shield her children from the international spotlight — while, at the same time, her husband was well aware of the humanizing effect his toddlers had on public image and didn’t hesitate to take advantage of it — “First Children” weaves a story of the innocence of childhood even in the midst of extraordinary circumstances. A highlight for me was the recreation behind glass of Caroline’s White House bedroom, filled with gifts from international leaders, and the display of her dolls (of which she received about 75 from foreign dignitaries across the globe). Close by, the exhibit cycled through a slideshow of photos depicting the room as it appeared at the time, complete with one of John Jr. grinning by his sister’s couch, where countless dolls are set up lovingly.

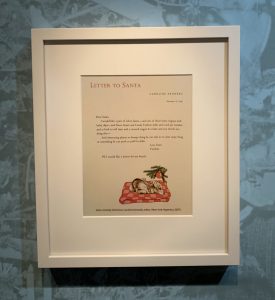

Pieces of artwork by both children and a letter to Santa from the last Christmas they spent with their father (wherein Caroline requests a “real pet reindeer” for herself and “interesting planes…or something he can push and pull” for her little brother) were other particularly special moments. These children lived lives that were anything but ordinary, in any sense of the word — yet they were still just children. It was a striking experience: these youngsters who we all feel we know so well, because American culture is so saturated with their likenesses, becoming so real.

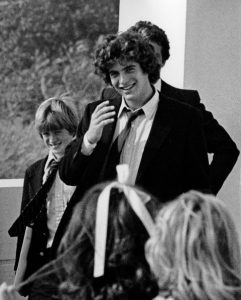

When the John F. Kennedy Library opened in 1979, the children — by this time 21 and 18 — were, of course, present at the dedication. John Jr., in fact, read a poem by Stephen Spender in honor of his father. “I think continually of those who were truly great,” it opens, ending with the lines “Born of the sun they traveled a short while towards the sun / And left the vivid air signed with their honour.”

Interestingly, in a moment that has since become famous, an adult John Kennedy Jr. told a friend that everyone expected him to become a great man, as his father had been. “I think,” he said, “it would be a much more interesting challenge to see if I could make myself into a good man.”

Taking my cues from the JFK Library, I won’t dwell on the unfair and untimely losses of either John Jr. or his father. But I believe this image — of a memorial outside the younger Kennedy’s apartment in 1999, including a sculpture of that famous moment — is too powerful not to include. It bridges two tragedies, two eras, two men, a little boy and his father — whether good or great. That’s up to history, and our collective memory. That’s up to museums.

The JFK Library is currently open Saturdays and Sundays from 10 AM to 2 PM; click here to reserve tickets online. “First Children: Caroline and John Jr. in the Kennedy White House” is on view through January 2023; learn about the special exhibit here.