This week’s post is brought to you by Melissa Kansky, a first-year student in the Museum Education M.A. program at Tufts,

Image 1 : (Bark Painting exhibited at the Art Gallery of NSW)

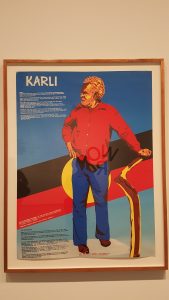

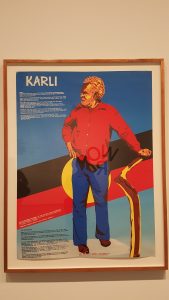

Image 2 (Political poster, Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia )

Museums provide a lens into a community’s cultural identity, as well as the social issues that define its history and development. During Winter Intersession, I had the opportunity to travel to Australia. While abroad, I relied on art museums to uncover the layered history of the unfamiliar place. Despite the unique character of each museum, they exhibited similar themes, revealing dominant questions that permeate Australian society. The national institutions consistently used their respective collections to address the country’s colonization practices and resulting injustices against the Aboriginal people.

Similar to museum practices in the United States, Australian museums have, historically, depicted indigenous culture as static and archaic. Displays of Aboriginal culture had been restricted to anthropological museums, which provoke visitors to associate Native heritage with primitive and obsolete populations. However, in 1959, the former deputy director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales advocated that the museum include Aboriginal works, moving indigenous culture from the domain of natural history into an art context. Although controversial at the time, the decision acknowledges that Aboriginal experiences contribute to present Australian identity and enable Aboriginal peoples to direct their narrative. Aboriginal artists produced the series of Bark Paintings, exhibited on the first floor of the museum, specifically for the gallery. As a result, the artists determined the way in which their culture was presented for public consumption. Additionally, wall text often includes the artist’s voice and perspective, permitting both artist and curator to contribute to the interpretive process.

In addition to elevating Aboriginal voice, museums also highlight persistent colonization practices. An exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia illustrates current issues regarding land ownership and indigenous rights. The temporary exhibit, “Word: MCA Collection,” contains political posters from the permanent collection. The posters respond to displacement and cultural appropriation. The contemporary collection indicates these social injustices are not confined to Australian history, but influence present political structures, showing that museums must be courageous enough to not only participate in, but also advance, challenging conversations that shape the country.

While Australia is certainly not perfect in its museum practice, the country offers a model for greater inclusion of indigenous perspective. In the United States, the Abbe Museum, located in Bar Harbor, Maine, has positioned itself as a leader in decolonizing museum practices, which demands sharing authority for the documentation and interpretation of Native culture. Nevertheless, indigenous collections have, largely, been limited to natural history museums, tribal museums, or indigenous-focused museums. In contrast, exhibitions in non-disciplinary museums expand where visitors encounter Native voice and the way it is incorporated in the community’s story. Museums that prominently feature Native artists signify that the experiences of marginalized populations are part of our national character.

![Education Programs Internship [Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, Boothbay, ME]](https://sites.tufts.edu/museumstudents/wp-content/themes/kale/sample/images/thumb1.jpg)

![Dangremond Museum Studies Internship [Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, CT]](https://sites.tufts.edu/museumstudents/wp-content/themes/kale/sample/images/thumb2.jpg)