Virtual Sessions of Hands-On STEM with Novel Engineering in Nepal Pt.1

This is the first part of a guest blog series by our teammate Dipesh Shrestha.

Overview

In June, a private school in Kathmandu reached out to Karkhana to engage around 400 students from grades 2 through 10 in hands-on STEAM activities, through virtual sessions. Our teachers would be in contact with the same set of students for 50 minutes each week for 3 consecutive weeks.

| Weekly Schedule | |||||

| Time | Sun | Tue | Wed | Thurs | Fri |

| 1:20 to 2:10 | 10 (Samaya) | 9 (Samaya) | 8 (Samaya) | 6 (Santoshi) | 7 (Santoshi) |

| 2:30 to 3:20 | 2 (Sunita) | 5 (Santoshi) | 3 (Rashmi) | 4 (Santoshi) |

Planning

Sunoj, Samaya, Santoshi, Rashmi, and Dipesh brainstormed ideas about how to best utilize the children’s time, while also managing the school principal’s expectations. We then decided to use the Novel Engineering (NE) approach for grades 2 through 7 and “Think like a scientist” activities for the remaining grades.

In the next meeting, Santoshi (new to NE), Rashmi (who had co-facilitated an NE session with Sunoj), Sunita (who had observed Sunoj running NE), and Sunoj (prior experience running NE) planned out the details for the sessions. Our teachers were concerned about the number of students who’d be attending the sessions. According to the school vice-principal, we were expecting somewhere between 20 to 60 participants, which would be difficult to engage in hands-on explorations, especially in a virtual setting.

In addition to that, the school principal had asked us to deliver the classes “strictly in English language,” which is a common thread in Nepal where English language instruction is associated with better quality education and something that sets apart private schools from public schools. Reflecting on my personal experience, we were fined 10 rupees if we were caught speaking in Nepali within the school premises. It’s disheartening to know that similar practices are still prevalent in schools in Kathmandu.

The 4 teachers came up with a general flow for the 3 days:

- Day 1: Read a story and identify problems + collect household materials for the next day

- Day 2: Identify solutions and design/build/make

- Day 3: Share what you made and improve designs

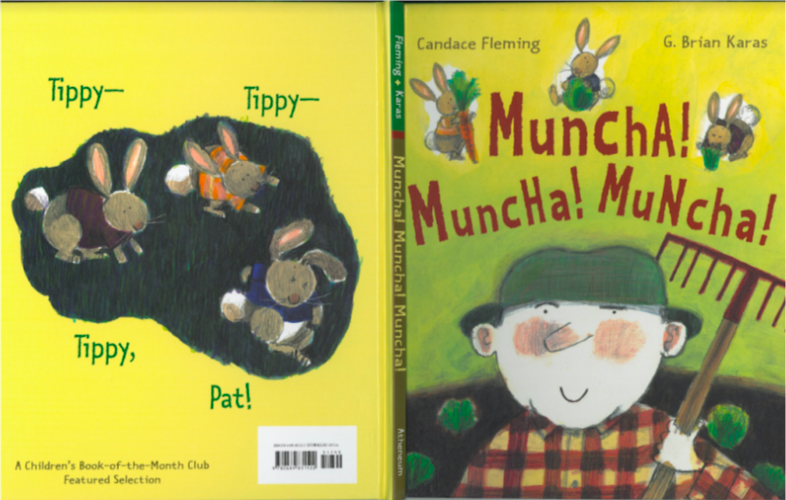

Figure 1: Muncha, Muncha, Muncha by Candace Fleming (author) and G. Brian Karas (illustrator)

Sunoj suggested reading Muncha Muncha Muncha because he had already prepared a lesson plan for a similar session and the teachers did not have much preparation time. After we gave Santoshi a brief overview of the NE approach, she mentioned that although the approach was interesting, she thought that “doing guided project based work might suit grades 6 and 7” because she felt that the story was too simple for higher grades. Sunoj told her that from his experience, “You’d be surprised with how engaged the students are,” and encouraged her to try the NE approach. He also shared a presentation slide deck to show her examples of what students had made in previous sessions. After Santoshi looked at the pictures, she mentioned “Kasto cute bunny banako raicha (Wow! They made a really cute bunny!),” admiring the projects that the kids had made. Rashmi also shared her experience co-facilitating such sessions and shared more examples where the kids came up with violent solutions (poison the bunnies, beat the bunnies to death) and how she had addressed those issues.

It was great to see how Santoshi and Sunita (newcomers) were being introduced to the NE community of practice by Sunoj, Samaya and Rashmi (old timers).

Week 1: Reading Stories and Identifying Problems

Grade 2 – Sunita

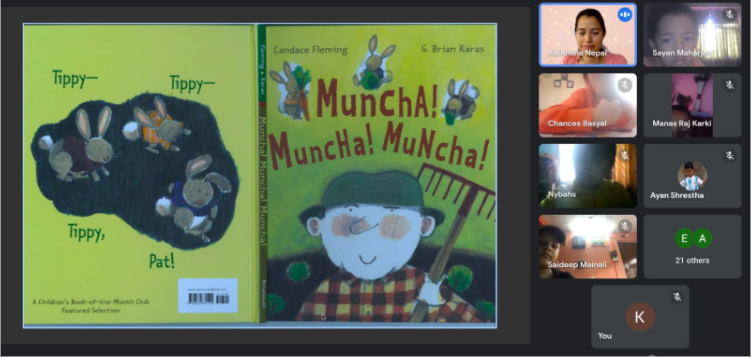

Figure 2: Sunit facilitating a session for Grade 2 students

In the Grade 2 session, there were 30 participants out of which only 6 students turned on their video and only 8-10 students interacted with the facilitator via chat or audio. Since this was the first class, Sunita had to spend some time in classroom management as the students were new to Google Meet, speaking out of turn, all responding at once, and interrupting their peers.

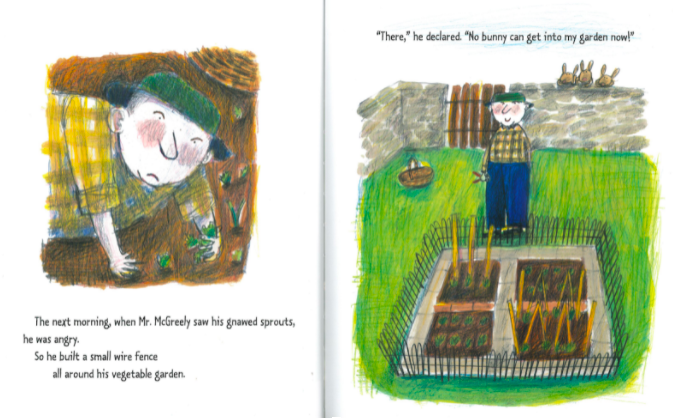

Figure 3: Sunit takes a pause to ask questions to the students

After reading each page, Sunita paused and asked questions to the students. Gradually, more students started responding to the questions and using the “Raise Hand” feature to eagerly wait for their turns. When asked to share what they had noticed in the above picture (Figure 3), they patiently waited for their turns and responded:

“Mr McGreely is standing and he has a garden with a fruit”

“In his garden there are plants growing”

“I think it is electric fence. Electric fence electrocutes everything it touches.”

Grade 5 – Santoshi

In the Grade 5 session, there were 38 participants out of which only 4 students turned on their video. In comparison to Grade 2, more students interacted with the facilitator via chat. When asked “What do you think Novel Engineering is?,” one student shared:

“Mam i found in google Novel Engineering encourages students to interact with literature in a proactive, hands-on manner. In this approach, students read stories appropriate to their grade level, then doff their literary caps in exchange for engineering ones. With each story they read, students determine a problem that the character faces.”

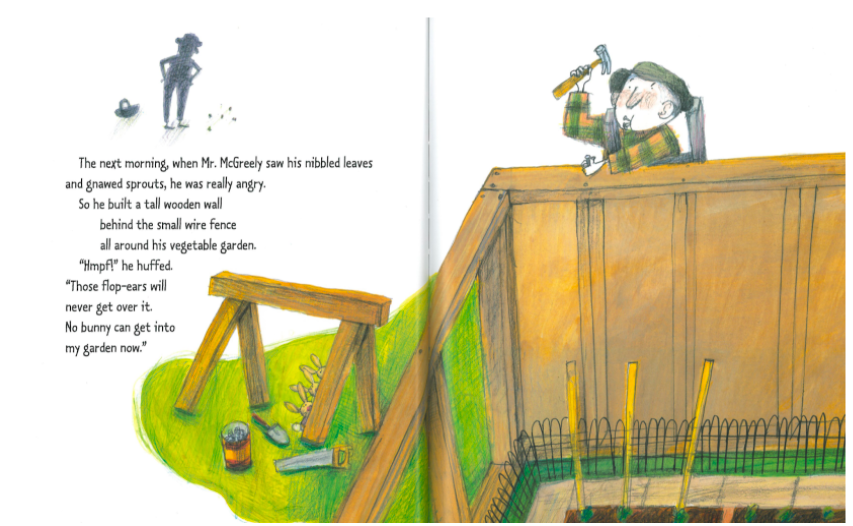

Grade 5 students definitely seemed to have more experience using online tools and preferred using the chat feature to respond to the facilitator. Santoshi paused (Figure 4) and asked the students “Do you think Mr Mcgreely will be successful?,” to which the students responded:

“The rabbits could jump no?”

“The rabbits could bite using teeth.”

“The rabbits could bite their wood with their front teeth.”

Figure 4: Santoshi takes a pause to ask questions to the students

After reading the story a second time, Santoshi asked students to identify problems in the story. Here are some of the problems they identified:

“The problem is that the farmer’s garden is not safe.”

“If he had just given little food the bunnies food, the bunnies would not have eaten his vegetables” (Santoshi: You’ve included the solution here)

“I have listed 3 problems: 1. There was no security from the bunnies at first, 2. There was no security from the bunnies until towards the end, 3. The bunnies were hungry when the garden was fully secured.”

Santoshi then asked “How can you use engineering to solve problems that you found?”

“Build a machine that would have taken out some of the crops and give it to the hungry rabbit.”

“The farmer can build a huge barrier or a huge wall.”

“He can send a cat to catch a bunny”

“He can catch the bunny using trap”

After observing the first two classes, both the teachers were excited to see the engagement from the students but were later disheartened when Sunoj sent us a group message:

“The co-ordinator sir called. He said the principal thinks it’s like an English class and where is science bhanera and he is also confused ray.”

(The school co-ordinator called. He said that the principal felt that our sessions looked like an English language class and she was confused because her expectation of Karkhana classes was that they’d include Science concepts.)

The teachers shared a concern that “Many school leaders in Nepal are still very old fashioned and have only seen traditional ways of teaching and learning and it’s sad that people at leadership positions do not understand the value of new approaches.”

Sunoj then called the vice-principal (our main point of contact at the school) and requested him “to let our teachers run the classes as we had planned,” and wait till the end of the cycle to give us feedback or suggestions. He accepted our request and told us “to do what we do best.” Encouraged by the vice-principal’s words, our teachers began planning for the next session.

Week 2: Coming Up with Solutions

Grade 2 – Sunita

In the second session for grade 2, there were only 16 participants. This allowed Sunita to interact with the individual students. After reviewing the story, she asked the students “Do you know what an engineer does?,” and they responded:

“They make house.”

“They make things.”

“Construct houses and building.”

“They build house and shops.”

“They make map and they design what to make.”

“They have a little map about designs.”

“Engineer makes many things like house, buildings, temples.”

“There are many types of engineers: civil engineer, electric engineer, computer engineer.”

“My father is also engineer.”

“The people who want to make house tell the engineer to make house like this and he constructs like they say. They also measure about windows, doors and how much land you need. Because I have already seen. My uncle is a engineer.”

As evident from the students’ responses, it is clear that young learners bring in prior knowledge about design and engineering as they make sense of the world around them. Further, there are plenty of opportunities to introduce ideas about “designing for clients,” something which naturally surfaced in this classroom discussion when a student shared her experience of seeing her uncle design houses for clients.

According to her plan, Sunita asked the students to note down gardening tools they had noticed when they read the story, and asked them “Do you have any gardening tools in your house? You can also say it in Nepali.” They responded: “kuto,” axe, hammer, scissors, rake, shovel, watering can.

Sunita then prompted them to draw some of the gardening tools they had seen around the house. As shown in Figure 5, they drew a rake, shovel, spade, watering can, “khurpa,” “hasiya”, and “kuto.”

Figure 5: Students’ drawing of gardening tools.

As the students were sharing their drawings, one student showed her friends some gardening tools that she found in her house (Figure 6), and seeing this another student brought another sharp object. Since we had not anticipated this, Sunita asked the students to be careful with the sharp objects and inquired if an adult guardian was nearby to observe them, and to our relief, someone was nearby. Apparently, the student was from a household that had a farm where these tools are in daily use. She later told us “My father mother has a ‘gai’ (cow) farm. They use these tools. They have 6-7 cow in their village. There are 5 cow baby.”

This incident reminded us that young learners also bring prior experiences like using tools, manipulating materials, participating in household chores, and observing others’ work, which might provide alternative pathways of introducing them to ideas of engineering and design.

Figure 6: Students demonstrating gardening tools (“khurpa,” “hasiya,” “choori”) that were in their homes.

Grade 5 – Santoshi

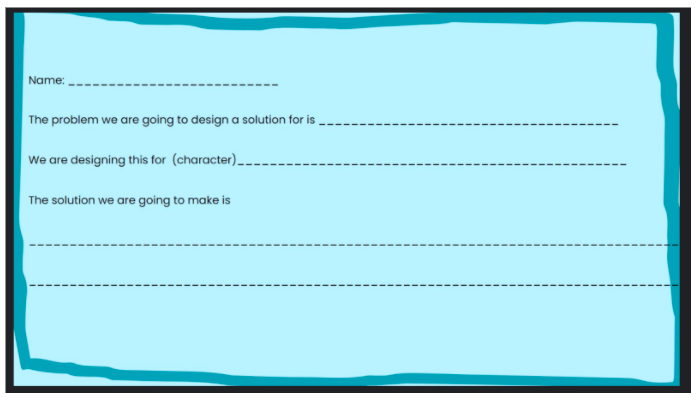

In the 2nd session for grade 5, there were 37 students with 4 new students who had missed the first class. Based on her conversations with Rashmi and reviewing the class observation notes from Sunita’s class, Santoshi decided to test a new activity. After reviewing the story, she asked the students to write their responses in a notebook according to the format shown below (Figure 7). Some students decided to help Mr. McGreely and proposed to build a huge fence or construct a secure building, others decided to help the bunnies by building a bridge or a tunnel.

One student had a different idea, she wanted to design gloves for Mr. McGreely because his hands would get dirty while gardening. We believe that the template Santoshi provided, encouraged this student to think about problems that Mr. McGreely was facing, other than keeping out the bunnies from the garden.

Figure 7. A template to help students structure their ideas as they identify problems and solutions

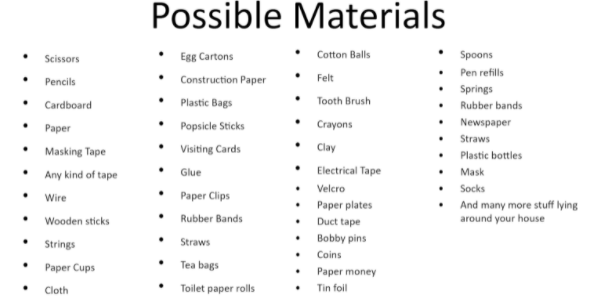

She then asked the students to collect materials by showing them a list of possible materials that they could use to build their solutions. The students were excited to search for the materials in their homes as this was a timed challenge. They ended up collecting cardboard, colors, shopping bags, buckets, tape, glue, scissors, and even a shoelace.

Figure 8. List of possible materials the students could find in their homes

Week 3: Building Solutions

Grade 2 – Sunita

In the final session for grade 2, there were 19 participants with 3 new students. According to her plan, she started the session with a game where children had to identify different objects around their homes.

- Identify things in your room that are red.

- Identify things in your room that are made of paper.

- Identify things in your room that you can use to draw.

- Identify things in your room that you make use to tie a knot.

The idea behind this game was to encourage students to think about different household materials they could use to build their projects. Once the students had identified these materials, Sunita gave them 3 minutes to collect 4-5 different materials from the list of possible materials (Figure 8). They collected cardboard boxes, chart papers, glue, scissors, product packages, styrofoam, and other craft materials.

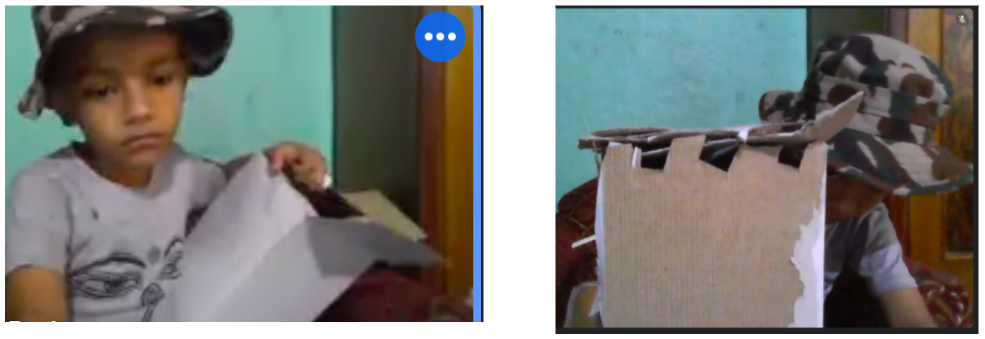

Figure 9: A student holding a box he had collected (left), and a “secure building” which he made using the box (right)

Figure 10: A trap to help Mr. McGreely (left) and a tunnel to help the bunnies (right)

The students used the materials they had collected (Figure 9, 10) to come up with engineering solutions to the problems they had identified. Some students chose to help either Mr. McGreely, while others chose to help the bunnies.

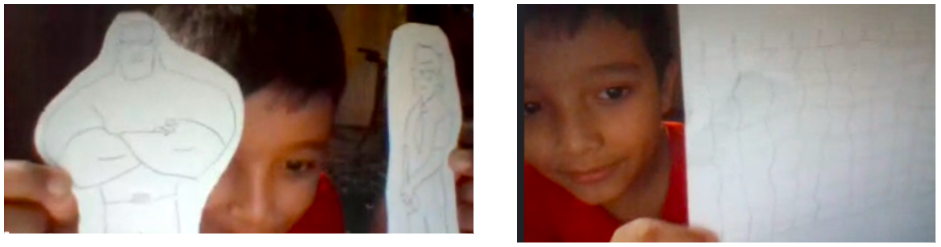

One student was visiting his uncle and only had access to papers, pencils, and scissors. So, he made paper cutouts of “bodyguards who Mr. McGreely could hire” to protect his garden from the bunnies. After appreciating the creative solution the student had come up with, Sunita then encouraged him to think about a solution that involved engineering. Since there was not much time left, he quickly sketched something on a piece of paper and shared that he would make “an electric fence” to keep out the bunnies.

Figure 11: Student’s first idea of making cutouts of “bodyguards who Mr. McGreely could hire” (left) and his second idea to make “an electric fence” when Sunita asked him to think of a solution that involved engineering (right)

Grade 5 – Santoshi

In the final session for grade 5, there were 25 participants (12 less than the previous session). The smaller group was more interactive and more students turned on their videos because they were eager to show their solutions to their teacher and peers. Here are some of the solutions the students came up with.

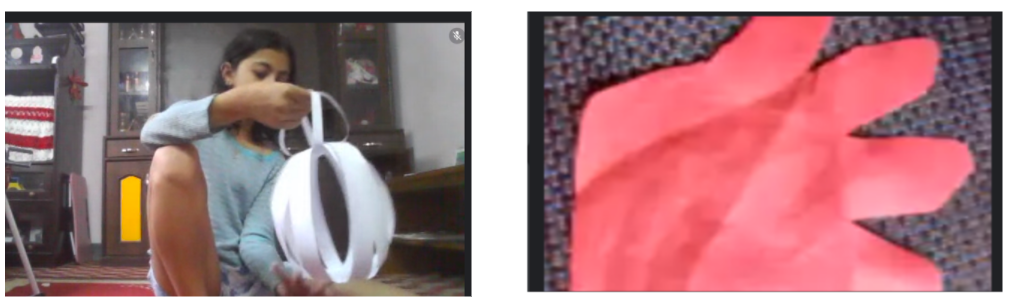

Figure 12: A wooden bridge (made using chopsticks) to cross the moat, and a rope (using string) to climb the huge wall (left image) and a scheme to lure the bunnies into following small pieces of carrot that leads to a trap (right image).

Figure 13: A trap with a door trigger that traps the bunnies as they enter the cage (left) which is also spacious enough for a person to fit in (right).

Figure 14: A cage you can use to trap the bunnies and carry them to a nearby jungle (left) and gloves for Mr. McGreely to keep his hands clean as he tends his vegetable garden

In Figure 13 (right), we can see the student who designed the trap, asking her mom to hold the phone camera so that all her friends could see her fit inside the cage. Similar to solutions that the Grade 2 students had designed, most of the students designed a trap or a wall to help Mr. McGreely but one student decided to design a solution for a different problem (Figure 14, right) as she mentioned:

“[Mr. McGreely’s] hand was dirty because of digging in the garden. So, I made gloves to help him.”

Grade 3 – Rashmi

There were also some innovative solutions that students in Rashmi’s Grade 3 session designed.

In the second session, one student had shared an initial design of what her solution would look like. Instead of just using paper to sketch a solution, she captured a screenshot of a page from the book which illustrated the problem she wanted to solve. She then used MS Paint to draw and label (log, hole) the elements of her design (Figure 15, left). Third, created a Google Slide presentation in which she uploaded her image. Finally, she shared that presentation with Rashmi. In the final session, she used materials she had collected to construct a physical model of the solution based on her initial design.

Figure 15: A student’s initial design (using MS Paint) of a solution to help the bunnies (left) and the model she built using paper and sticks (right), in the final session.

Another interesting observation while the students were working on their projects was that of a student who skillfully used various tools to build her solution. Since Kathmandu was still in a lockdown mode because of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, she had to rely on whatever materials were available in her house. She used a kitchen knife to carve out slots in a toilet paper roll. Likewise, she used a compass to poke a hole into a piece of cardboard, and made the hole bigger by using a pencil. Although these images might be shocking for some teachers and parents, we were impressed by the care and skill the student used to craft her solution. Further, she also recruited her younger sibling to help her complete the project on time.

Figure 16: A student using various tools like a knife (top left), a compass (top right), and scissors (bottom left) to build her solution. She also involved her younger sibling in helping her complete her work on time (bottom right).

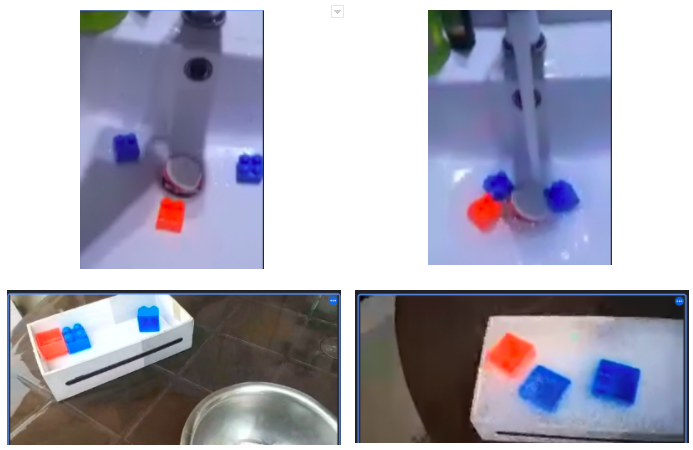

Another student used LEGO bricks to demonstrate her solution. For her first iteration, she actually went to her bathroom sink to experiment whether her solution would work. In her experiment the bunnies (represented by the 3 LEGO bricks) would stay afloat as the water level rises and once they reached the top of the wall, they could easily hop over it. After her successful experiment, she then created an improved setup using kitchen utensils to showcase her idea in the final presentation.

Figure 17: A student’s first iteration (an experiment she ran in her bathroom sink) in which the bunnies (represented by the three LEGO bricks) would stay afloat and climb the fence as the water level rises (top two images) and her second iteration in which she used kitchen utensils to demonstrate an improved version of her solution (bottom two images).

We were impressed by the variety of materials the students were able to collect in their homes which they adapted, modified, manipulated, cut, joined, and glued to come up with creative solutions. In Figures 18 and 19, we can see students utilizing different materials like cotton, felt, pieces of cloth, paper clips, strings, wood, nails, wooden sticks, and paper to build a solution. As shown in Figure 19, even if their solution was the same (Eg. to build a ladder), the products they built were different.

Figure 18: A student used cotton (representing rocks), felt (representing sand), and pieces of cloth (representing grass) to block the borrows the bunnies might dig (left) and another student used a block of wood, strings, and plastic bag to design a trap (right).

Figure 19: A student made a ladder using paper clips tied to a string (left) while another student made an actual life sized ladder using wooden sticks (right).

Closing Thoughts

Although I had seen examples of student work, attended presentations that introduced the Novel Engineering approach, and read related research papers, this was actually my first time observing teachers using an NE approach in the messiness of a classroom. I appreciate the care and effort the teachers (Sunita, Santoshi, and Rashmi) put into designing lesson plans using the NE approach while also navigating the added complexities of implementing hands-on making activities in a virtual setting.

As evident in the examples we have shared in the previous sections, it is clear that young learners bring in prior knowledge about design and engineering as they make sense of the world around them. Also, the incident with the “sharp objects (Figure 6),” reminds us that young learners also bring prior experiences like using tools, manipulating materials, participating in household chores, and observing others’ work, which might provide alternative pathways of introducing them to ideas of engineering and design.

Likewise, we were fascinated by the variety of materials the students were able to collect in their homes which they adapted, modified, manipulated, cut, joined, and glued to come up with creative solutions. Also, students skillfully used a variety of tools (both physical and virtual) to build their solution. As shown in Figure 16, students showcased care and skill in using tools as they manipulated materials to create their desired solutions. Similarly, as shown in Figure 15, students skillfully utilized virtual tools (MS Paint, Google Slides, capturing screenshot, Gmail) to communicate their ideas.

Since learning is a social endeavor, we could see multiple instances where students involved a guardian (Eg. The student asking her mom to hold the camera phone in Figure 13) or a sibling (Eg. students recruiting their siblings to help them complete their builds in Figure 16, 18) to help them locate materials, brainstorm ideas (“use a shoelace, instead of a rope”), provide suggestions (“kuto bana na”), and offer assistance (holding the wooden block in place) in their learning process. Students also explored spaces in their homes (kitchen, bathroom, garden, farm) as they searched for materials and designed their own experiments (Figure 17).

Further, we also realized that the books in the NE approach provide plenty of opportunities to introduce ideas about engineering and designing for clients. Also, providing a structure (Eg. The prompt Santoshi used in Figure 7) might encourage students to think about problems from different perspectives which in turn might influence the solutions the students design (Eg. The gloves a student designed in Figure 14). Likewise, asking students to think about integrating engineering solutions, might challenge them into thinking about functional solutions (Eg. Moving from “hiring a bodyguard” to “building an electric fence” as shown in Figure 11).

We hope these observations will be useful for teachers who want to implement a Novel Engineering approach in their classrooms. Hopefully, the evidence we have shared in this writeup will convince school leaders, parents and other stakeholders of the value that the NE approach and hands-on making, adds to students’ learning.

In the next blog post, I will share observations and insights of facilitating a Teacher Development session for classroom teachers in Nepal and further iterations that Karkhana teachers have been trying: like collecting traditional folktales, identifying rich texts in Nepali language, reviewing the national curriculum to locate texts that might be suitable for an NE approach, and designing a learning progression to introduce these ideas to other educators.