Insights on Integrating a Novel Engineering Approach to Physical Computing Workshops

Between mid-September and mid-October, 2021, I (see Author’s introduction at the end of the post) along with my colleague Hasin Shakya designed and delivered a series of online workshops titled “Coding for non-coders” for the staff of American Spaces and their partner organizations from South Asia.

The objective of the workshop was to get the participants, most of whom were unfamiliar with the concept of coding, familiar with the basics of coding and electronics. A parallel objective was to let participants experience various approaches to facilitate engaging sessions in a makerspace setting, so that they could run better sessions at their respective spaces. The workshops revolved around Arduino, an open source microcontroller, which was used to introduce the participants to coding through physical computing.

We asked the participants to work on a culminating project where they could utilize everything they had learnt in the workshop so far. I had been introduced to the approach of Novel Engineering (NE) through the Tufts CEEO Tech&Play initiative. I had taken quite a liking to the idea, and thought it would be a good fit for the final workshop because in addition to being an engaging way to guide participants towards a culminating project, it was an effective way to integrate social sciences and literature to STEM. Hasin and I were quite eager to test this approach to a group of adult audiences. Most of the participants in this series were from the age group 30 to 40 years, with a few being below 20 and above 40 years old.

Selecting the Stories

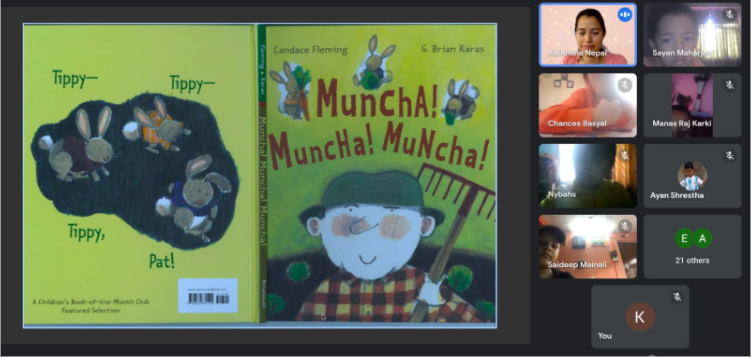

As we planned the workshop, the first challenge we faced was regarding the selection of an appropriate story. From my experience of creating an NE lesson as a participant in the research group, where I was first introduced to NE, I knew that not all stories can be used for NE. Moral tales and fables are among the least appropriate choices for an NE activity because usually there is a unidirectional approach to the problem and the story is woven to point directly at a solution in the form of a moral lesson. On the other hand, most bedtime stories seemed like great choices due to the wide range of characters, plot twists and multiple problems that occur as the story progresses. For the first workshop, we decided to play it safe and chose Muncha Muncha Muncha, written by Candace Fleming and illustrated by G. Brian Karas, because I had prior experience with the story as a participant. In the second workshop, we had more insights into the NE approach and were more confident about the use of a new story. Some of the insights we received from the first workshop are listed below.

- Participants unfamiliar with each other often try to be agreeable to their group members. This prevents healthy debates from taking place, and ideas from being fleshed out.

To tackle this problem, facilitators need to move around the groups and play the role of devil’s advocate.

- Despite having been given the guidelines for the ideation phase, many participants will need reminders to implement them.

- Participants might want to modify the solution as they get new ideas while prototyping. So, it’s better to not spend too much time defining solutions and give more time to prototyping.

- Not all feedback is useful. One group from the first workshop made changes as per feedback which resulted in additional problems in their prototype.

We made a note to remind participants that not all feedback is useful and they need to use their discretion to filter them.

For the second workshop we chose a folk tale from Kathmandu titled The Lattice Window. We modified the lesson plan as per the insights from the first workshop and saw a more positive outcome in terms of participant engagement, project completion rate and peer learning.

Challenges and improvisations in Design

While designing the workshops, the key challenge for us was to make sure participants get a proper taste of the NE approach without compromising the work they were supposed to do using Arduino for the projects. To make the process of defining problems and ideating solutions quicker and collaborative, we decided to incorporate ideas to make their thinking visible. For this purpose we used a thinking routine named Circle of viewpoints, created by Harvard’s Project Zero. Thinking routines are structures that are used to scaffold and support students’ thinking. There are more than 40 thinking routines, each with its own specific purpose. We selected the Circle of viewpoints because the NE approach required participants to take on the perspective of a character from the story – something that the thinking routine is designed for. We adapted the thinking routine into a Miro template so that participants can collaborate easily. The template is shown below.

We also used the How Wow Now method, commonly used to select best ideas from a pile of ideas. This was done to make it easier to organize the solutions and select the optimum one for prototyping. The Miro template of this structure is shown below:

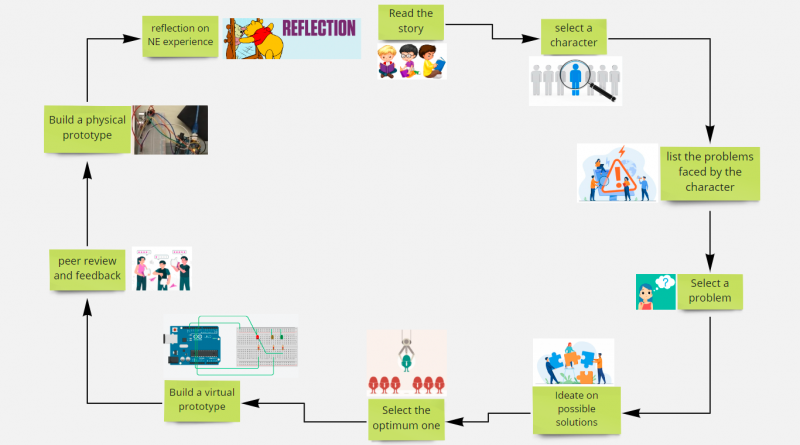

The workshop flow was based on the NE workshop I had attended in the research group. We made a few improvisations to the flow which I’ll explain in the next paragraph. The flow of the workshop is shown in the diagram below.

The first improvisation we tried was asking participants to pick a character whose perspective they wanted to take. In the research group’s workshop, we had directly listed the problems we saw in the story. This improvisation was made to help participants avoid the confusion that I had noticed my peers were having. Normally, participants tend to list the problems that are faced by the protagonist of the story. Asking them to pick a character encourages them to notice problems of other characters as well.

Next improvisation we tried was making use of thinking routines. We have already talked about it in one of the earlier paragraphs. In the research group experiment we had made our thinking visible by posting our thoughts on Jamboard. We added a structure to the process, through thinking routines. We observed that the use of thinking routines made the process more efficient and clear to the participants. The use of the How Wow Now method helped the participants compare their solutions better as they were able to judge the ideas more objectively. Participants in the discussions had mentioned that normally they would go along with the solution that felt most appropriate. But the use of How Wow Now helped them see the feasibility and effectiveness of each idea, thus making their choice more reliable.

Before delivering the first workshop, we conducted a mock workshop to test out some segments we weren’t confident about. This resulted in more insights which are listed below:

- While thinking about the problems participants

- Tend to focus on the obvious ones that have been specified in the story

Let’s suppose problem A is directly mentioned in the story. But B might be the cause of problem A. For example, in Muncha Muncha Muncha, bunnies invading the garden is a direct problem. But that problem might have been caused by depletion of the food source due to deforestation and human settlement in the area.

Also, suppose solution C is generated in the story to solve problem A. But in the long run, solution C might cause problem D. For example, in Muncha Muncha Muncha, farmer McGreely builds really tall walls around his garden to keep the bunnies away. While this solution does prevent the bunnies from entering the garden, it also blocks the sunlight in the garden which can result in poor nourishment of his veggies.

- Tend to write only a word or two to indicate the problem, just enough for themselves to know what it is. It not only creates difficulty while collaborating but also prevents the individual from having a clear understanding of the problem.

- Another confusion that can arise is that if a problem is already solved as the story progresses, should we still mention it?

- When participants are asked to pick a problem, they usually pick problems based on intuition, interest, guess, challenge level, etc. It might cause problems while working in a group with varied interests.

- To make this process of choosing problem more rational, a structure like How Now Wow, which has severity in y-axis and difficulty in x-axis, might be useful

- If participants pick a complicated problem, they end up wasting a lot of time before coming back to choosing another problem to work on

- One of the participants from the mock session pointed out that ideation through the thinking routines helped them identify feasibility of solution early and save time

We also put more emphasis on the guidelines for participants during the making thinking visible phase. This was based on the insights we got from a mock session and from the reflections of my experience as a participant in the research group session. These insights are listed below:

- While defining problems as well as ideating the solution, participants tend to keep it too short, often no more than 4 words. This can be seen in one of the Jamboards we used in the session.

- While collaborating in a group, it makes it difficult for members to understand each other if the ideas aren’t elaborated properly. For example, one member of my team had written “maybe the location wasn’t right” as one of the problems. I had to ask him to elaborate what he meant by it. Similarly, we had to spend a significant amount of time simply explaining our notes to each other.

- Participants often tend to focus on the problems faced by the main character. In the workshop, all the participants had listed the problems faced by farmer McGreely. I was surprised to see that no one had considered the bunnies’ perspective.

Below are the guidelines we come up with to tackle the problems we noticed.

- Pick problems independent of how the storyline evolves (a problem can have multiple solutions)

- Be specific, define the problem well (participants are clear about what they are thinking)

- Pick some radical, fun problems (less concern about being too practical)

- Also think about the less obvious problems (causes and effects)

Another thing that we were worried about was that participants, being new to the NE approach, might list inappropriate problems and ideas for solutions. What I mean by the word inappropriate here is that something that can’t be easily converted into an effective prototype. To tackle this, we asked each group to present their work on the Miro board. At the end of each presentation, we questioned the group to make them think about how these ideas could be converted to prototypes. If any group felt that they weren’t clear and needed to rethink the problems or solutions defined, we asked them to use the first few minutes of the prototyping phase for it.

Making, Sharing and Feedback

While building the solution, participants first made virtual prototypes of the circuits in Tinkercad and simulated them. Then they briefly presented their prototypes among their peers and received feedback from them. Some of the virtual prototypes are shown below:

Next, they built the physical models from the virtual prototypes. They did a final presentation of their work and we moved on to the reflection part. Some physical prototypes are shown below.

What difference did the stories make?

The first workshop had more participants than the second one because the dates for the second workshop coincided with the Indigenous People’s day holiday for the American Spaces, which nearly halved the participant turnout. Less participants meant that they could work in smaller groups and more time could be provided to each participant during the discussions.

The story for the first workshop was Muncha Muncha Muncha. We thought it provided a solid foundation to generate Arduino based solutions. For the second workshop, we wanted to use a story from Nepal, as a cultural exchange and novelty for the participants. We went through the Asia Foundation’s Let’s Read books and selected a story titled The Lattice Window. The stories made a significant impact on the kind of problems listed. The problems identified in Muncha Muncha Muncha were focused more on engineering and technology based issues, while the problems from The Lattice Window were focused more on social issues. The screenshots of the problems defined in both cases are shown below.

What were the participants’ reflections?

The reflections were focused on three categories: simulation and prototyping, overall experience of the series, and the NE approach.

A question we asked during reflection was – How was designing solutions based on Novel Engineering different from designing solutions for a given problem? Some interesting reflections mentioned that they got to see NE as a way to make technological solutions mindful of the other related issues, such as environmental or social. One participant had compared the NE approach with a simpler version of a case study where students aren’t just directly solving the problem but are understanding the complete scenario before generating the solution.

Another participant, who attended the second workshop talked about change in his own perspective in regards to making-based engagements for his son. Prior to this workshop he had considered them unnecessary but after the NE session on The Lattice Window, he felt that he was behaving like the adults in the story by not letting his son have his say about his learning related engagements.

Another participant, who is an instructor in an organization that conducts making based classes for children, summed up her experience with NE as fun. She compared it to her usual way of delivering such classes and said that while the usual teaching method is instruction heavy, it doesn’t allow students to explore scenarios,identify their own problems, and ask their own questions. She recalled her childhood days as a student and said that the traditional process of working on projects where the end result is already decided and that the students try to build the solutions isn’t broad enough for students. NE, on the other hand, offers a lot more freedom, engagement and fun for students. She added that the use of thinking routines to identify problems and generate solutions was helpful in getting one’s thinking clear.

Facilitator’s reflections from the workshop

After each of these workshops, Hasin and I sat together to reflect on how it went. We were glad how well the NE approach was received by the participants. It also seemed like an appropriate closure to the series.

We were looking forward to seeing some participants take on the viewpoint of Kwan, the antagonist of the story The Lattice Window. We thought it would be interesting to see the insights and solutions this would generate. We were disappointed as all of them preferred to go along with the “right” side. Besides that, a few of the participants weren’t able to complete their projects. We would have loved to see them relish their completed project and were dismayed slightly.

We have grown fond of the NE approach and are looking forward to implementing it in our future classes and workshops. I had heard of the NE approach a year before I became a part of the research group. My limited perception of NE back then had been that of a way to extract prompts from novels and movies. I believed that it was just to make the classes more engaging and relatable to students. My perception changed after I experienced NE as a student. Later, after exploring NE as a facilitator in these two workshops, there has been a further change in the way I looked at NE. I see it as an ingenious way to integrate literature with STEM. The biggest strength of NE, in my opinion, is the opportunity it provides for students to empathize with the characters whose problems they are solving. This reminds me of a video by The GlobalPOV Project we had watched in the seventh week of research study. It talked about how new problems are born when “experts” tackle a problem without complete understanding of it, and questioned if such experts can ever solve the problem of poverty. I think NE provides a sound solution to this problem of “experts” as students get to understand the problem in a greater depth, have the freedom to pick their own problem, and design the solution accordingly. Another wonderful benefit of NE is that it’s applicable to all age groups. Literature appropriate for an age group can be picked and students can develop solutions for it. The choice of stories can range from Rapunzel to The Most Dangerous Game to Jane Eyre, depending on the students, or the central issue being addressed.

Author’s Introduction:

Sameer Prasai is a teacher and researcher at Karkhana Samuha. He primarily designs learning resources, lessons, and workshops in the field of Digital Literacy, Computational Thinking, and STEM. His interest lies in designing meaningful learning experiences.

Before joining Karkhana Samuha, Sameer was a teacher at Karkhana. He has also taught at elementary and middle school level. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Visvesvaraya Technological University, Karnataka, India.