Microcredit: A Business Tool, Not a Band-Aid

A review by Lucy Mastellar under the supervision of Kim Wilson

Image source.

Many refugees remain “stuck” in protracted transit for decades. Though refugees receive basic humanitarian aid, few have opportunities to engage in money-making ventures throughout their journeys. The provision of microcredit has been proposed as a way for refugees to garner greater income and self-reliance while in transit. However, according to a recent Journeys Project collaboration titled “Formal Microcredit for Refugees: New Evidence and Thoughts on an Elusive Path to Self-Reliance,” the complexities of refugees’ temporariness and legal status limit the success of entrepreneurial-focused microcredit programs, particularly in Jordan. Refugees instead rely on their own social networks for financial security. Below, guest writer Lucy highlights the pros and cons of microcredit found in the aforementioned report.

Conventional approaches to poverty reduction have promoted microcredit as a form of financial self-sufficiency and entrepreneurial independence. Though the provision of microcredit is commonly applied in localized contexts, various international organizations have expanded microcredit aid to refugees. Refugees have active, albeit precarious, financial lives, thus microcredit is promoted as a way for refugees to generate income and reduce their reliance on humanitarian aid. However, a joint report conducted by the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt and The Fletcher School at Tufts University denotes microcredit’s limited ability to reduce poverty and improve financial resilience in displacement settings. The report substantiates its claims via research compiled in Jordan between March 2019 and December 2020. Authors conducted 428 interviews with refugees and migrants located in Jordan, Kenya, Uganda, and Mexico to determine whether financial services supported their efforts to integrate into their local economies. The report concludes that refugees’ unique legal barriers and uncertain futures inhibit their ability to leverage most financial services. Aside from remittances, researchers found that most financial services were not of particular use in refugee economies.

In Jordan, the report’s authors closely examined the use of microcredit, widely haled as an important input for Syrian refugees. Instead of finding microcredit useful, refugees relied on informal, community-based loan networks, including corner stores, to meet their financial needs. For the few refugees who did use microcredit, such financing was typically used for recovery from a financial setback rather than entrepreneurial engagement. Though microcredit had the ability to improve refugees’ financial health, only some individuals had the entrenepuerial skills and networks needed to benefit from debt.

The study found that for financial services to be useful, refugees needed to have a means of earning an income. Once stable and growing livelihoods were in place, along with the right to work or start businesses, refugees’ need for financial services evolved. Savings, credit, and payment systems, like M-PESA, became useful.

For microcredit to create value, refugees must leverage their assets. For this to happen, microcredit must be provided alongside increased rights, such as the right to work, and other services, such as cash assistance, skills-building programs, and childcare. Microcredit is a “good” form of debt only if refugees have the legal rights and tactical skills needed to succeed as entrepreneurs.

The Emergence of Microcredit for Refugees

Microcredit is the provision of small loans to low-income entrepreneurs, many of whom would otherwise be ineligible to receive conventional bank loans. Microcredit purportedly allows individuals to gain financial autonomy, typically via self-employment in the informal sector. In theory, microcredit is provided for entrepreneurial enterprise, inclusive of society’s poorest members. In practice though, the small loans are put towards other uses, such as school fees or the purchase of food and clothing.

In refugee settings, immigrants often lack access to regular work. Any additional debt causes a setback, not a leap forward. However, though little evidence purports that microcredit is helpful, many organizations still tout it as a practical means towards self-sufficiency. While refugees do have high rates of loan repayment, making microcredit a seemingly attractive option for lenders, their loans are not necessarily invested in their businesses. Still, microcredit is promoted as a way for “credit-ready” refugees to financially integrate within host societies while lowering dependence on foreign aid.

Image source.

Barriers to Financial Independence

The impacts of microcredit are difficult to assess. Microcredit measurements are largely contextual, and its long-term success is not guaranteed. Within refugee communities, microcredit’s focus on entrepreneurship often fails to address refugees’ core financial needs. Microcredit presumes that refugees can readily pursue financial opportunities, despite existing barriers. For example, a refugee’s existing bills and debts may prevent them from starting their own enterprise. New debt would simply be used to pay off older debt.

A refugee in need of food or medical assistance would prioritize these expenses. This leaves little room to invest in an enterprise. Microcredit then becomes a coping mechanism for refugees, many of whom use small loans from microcredit institutions to finance personal debts and recover from financial shocks. Financing is not used for microenterprise startups, as conventionally thought, but used instead for basic needs. By fixating on the provision of microcredit, development institutions overlook the benefits of direct cash assistance and medical aid programs. Rather than offer debt, humanitarian organizations might put their energy towards addressing refugees’ immediate needs, such as food and employment security. Once refugees have basic services and crucial rights in place, including the right to work, they are better equipped to deploy microcredit as a tool to advance business growth.

Though relatively few refugees use microloans, refugees do rely on their own informal networks for financial assistance. Refugees in Jordan used communal borrowing to finance their day-to-day lives, which despite its indication of poor financial health does offer some support. Loans from family, friends and the corner store offer multiple benefits, which include flexible repayment schedules, fewer late payment penalties, and little paperwork.

Personal relationships enable refugees to borrow within their own communities, furthering their ability to negotiate loan terms. Community lending relies on communal trust and accountability. Though informal, refugees are likelier to engage in community lending systems than in official loan agreements. Refugees prefer to negotiate lenient loan repayment plans with informal lenders when possible. Formal microcredit is, however, used for larger sums (i.e. $700 USD) when refugees fail to raise money via their informal networks. When used as a financial crutch, microloans can increase refugee vulnerability. As failure to make repayment deadlines may result in jail time (in the case of Jordan) or other repercussions, governments and NGOs must adopt new ways to address refugees’ critical needs. Microcredit should be promoted as a business tool, rather than an immediate financial remedy.

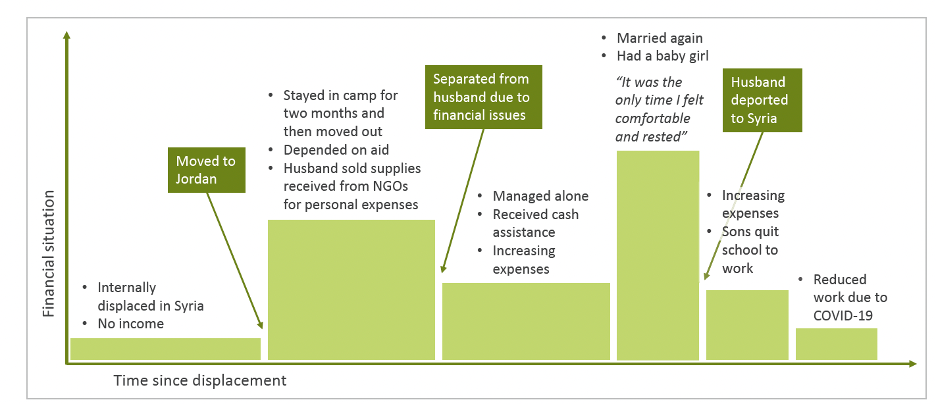

Zaheen’s Story

Zaheen is a 36-year-old participant whose experiences, among others, were used to substantiate this report’s claims. Zaheen’s emergency cesarean section left her with $700 USD in medical bills. Unable to pay these bills on her own, she turned to a microfinance institution (MFI) for a loan. Zaheen was confident that she could make all required monthly payments on the loan. However, after her husband was deported back to Syria, Zaheen struggled. The microfinance loans amplified Zaheen’s stress levels and increased her financial vulnerability. She eventually financed her formal loan via informal ones from her friends and family. The loan entrapped Zaheen in a cycle of financial insecurity, which forced her two sons to quit school and find work. As humanitarian cash assistance programs further reduced her family’s income, Zaheen grew anxious. Although microcredit helped Zaheen afford a vital medical surgery, this same loan sent her down a financial spiral. Instead, direct medical and cash assistance may have more positively benefited Zaheen. With no intention of starting her own business, Zaheen’s experience emphasizes microcredit’s entrepreneurial focus as unattainable.

A False Hope?

Microcredit is argued to shift the welfare burden of humanitarian actors onto refugees. Microcredit is beneficial when used for entrprenuial ventures; however, few refugees have the initial resources needed to jump-start a business. For refugees who do use microcredit for legitimate business financing, legal barriers abound. Rigid permit and financing legalities, for example, impede the success of refugee enterprises. Refugee business owners in Jordan must find Jordanian business partners. Additionally, existing anti-refugee sentiments and limited labor market access make local collaboration difficult. Jordanian work permits cost up to $950 USD, which few refugees can afford. Employment and legal limitations are not limited to Jordan, as few transit countries worldwide offer formal work opportunities for refugees. Should microcredit be promoted as an effective development tool, transit countries must work to ensure that refugees have access to local job markets.

Uncertain futures also prevent refugees from seeking out microcredit. With ambitions to move abroad or return to their country, many refugees are hesitant to establish businesses in temporary spaces. Refugees fear that, upon resettlement, they will lose their assets earned in-transit. A lack of foundational rights constrains refugees’ incomes. For refugees stuck in perpetual transit, employment inequalities and indeterminate transience prohibit effective implementation of micro-financed ventures. Amidst economic and legal uncertainties, few refugees can risk new business endeavors. Despite efforts to financially empower refugees, microcredit is not an effective tool for poverty reduction. Instead, international actors must work to address refugees’ exclusion from economic and political spheres in transit countries. Financial services must also evolve as refugees’ livelihoods change throughout their journeys, with mainstream services designed to improve their integration within host societies.

Image source.

Future Roads to Entrepreneurship

This report’s findings highlight the primary challenges associated with refugee entrepreneurship. Legal barriers and situational uncertainties prevent many refugees from establishing businesses and seeking out formalized work opportunities. Entrapment within temporary spaces further exacerbates refugees’ financial hardships. Refugees lack the most basic economic rights and are unable to comfortably survive on humanitarian and governmental assistance. Despite actors’ efforts to increase financial independence via microcredit, its implementation can lead to antithetical results.

Microcredit is an effective development mechanism in certain, well-defined circumstances. For refugees, microcredit should be one provision among many throughout their journeys. Financial services for refugees must evolve alongside their own journeys. Notably, the Journeys Project’s findings from Colombia highlight the need for growing financial services as migrants’ livelihoods evolved. Within Colombia, refugees either had the de jure right to work via a ten year residency visa or a de facto right to work as local authorities turned a blind eye to their activities. In either case, migrants searched for ways to maximize their money or to stay afloat. Entrepreneurial Venezuelans living in Cartagena and Medellín borrowed from local moneylenders called prestadiarios. These lenders charged exhorbitant interest rates, some as high as 30% of the loan’s face value, with rigid payback periods (often within a single month). Yet, such punitive loan terms still helped Venezuelan entreprepreurs, many of whom ran multiple businesses. In these cases, a friendlier loan provision such as microcredit would have been useful.

For the effective provision of microcredit, refugees must have some form of income. As jobs are often the first step to economic self-sufficiency, governments might consider increasing employment opportunities. Once employed, refugees would need access to additional services like affordable childcare and transportation. For their part, international institutions might work to expand working rights and social services, and offer ways to navigate complicated bureaucracies that often hold the key to critical documentation.

For financial services like microcredit to be useful, refugees’ foundational rights must be in place. Refugees should have the right to work, to open businesses, and to move freely. Such rights will ensure that refugees’ access to financial services effectively compliments their income streams and that credit will eventually be deemed both desired and useful.

Lucy Mastellar is a graduate student at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

For questions, please reach out to Professor Kimberley Wilson at Kimberley.Wilson@tufts.edu.