Migrants’ Financial Livelihood Progression Across Contexts

How do migrants and refugees rebuild their livelihoods, and what role does the host country have in their financial journeys?

In this issue of Fresh FINDings we take a look at each phase of livelihood progressions that we observed across research participants in both welcoming and less welcoming economies.

This month…

Financial Health of Migrants and Refugees: Stories Illustrating Livelihood Progression Phases

Livelihoods Phases

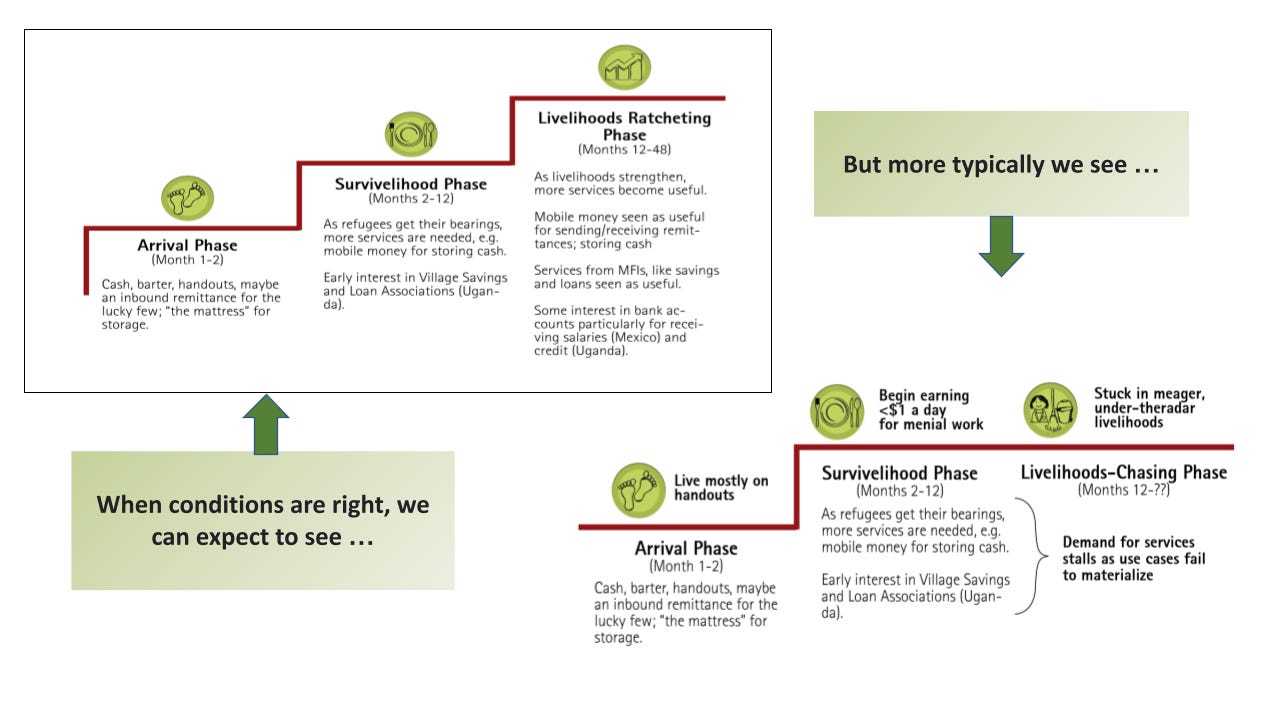

As migrants and refugees attempt to rebuild their lives in a new country, they face obstacles to permanent progress due to legal restrictions to move and work, discrimination from employers and their new community, and personal setbacks. Our research revealed how these experiences impacted participants’ ability to establish their livelihoods.

In situations where refugees and migrants had permission to work, open businesses, and had some legal protection (what we have come to call “welcoming economies”). We observed people ratcheting up their livelihoods. But, where they did not (i.e., in “less welcoming economies,”) their livelihoods flatlined.

The stories below depict what this trajectory looks like in practice.

Arrival Phase

An Example from a Welcoming Economy

Uganda

Isabelle and her husband fled to Uganda from DRC. Their arrival phase was marked by informal assistance and handouts. Their first week was spent at a police station where they could get their necessary refugee papers. There, the officers gave them leftover food and they slept on the veranda of the station. They also encountered other Congolese refugees like the woman who opened her home to Isabelle and her husband for three months. During that time, the Congolese woman provided housing, and they received food from religious organizations in the area.

An Example from a Less Welcoming Economy

Jordan

Zaheen, a 36-year-old Syrian female participant living in Jordan, is the head of one household in the Arrival Phase of her journey. She arrived in Jordan in early 2013 with her husband, two sons, and one daughter and stayed at a camp for a few months. She was divorced shortly after arriving. At this point, Zaheen relied completely on humanitarian aid to provide for her family until she remarried a working man whose salary was able to cover their rent. Still, Zaheen depended on cash assistance from UNHCR and WFP to meet her children’s needs.

Zaheen incurred an additional monthly cost in medical bills when she had her youngest daughter by caesarean section. A month after she gave birth, her husband was deported back to Syria, leaving Zaheen alone with four children. She was able to pick up work as a housekeeper and continued to rely on assistance from UNHCR and WFP for basic needs.

Survivelihood Phase

An Example from a Welcoming Economy

Mexico

Houston—a former child soldier in El Salvador and FBI informant in the US—began working without pay doing janitorial work at a migrant shelter in Mexico. Eventually, he was put in charge of the minors’ ward, teaching them technical skills, then joined a team to open a new chapter of the shelter, but still without pay. Houston then moved to work for family members of a priest he knew who paid him under $40 per week despite putting in twelve-hour workdays. So, he went to Tijuana and stayed on the floor of a former shelter resident.

In Tijuana, Houston found work at a manufacturing plant where he was paid $59 each week. Despite the low wages, he was able to save to afford his own rent. To build a more sustainable life for himself, he left the manufacturing plant to work for a man in construction, getting paid $89 each month until he was offered a management position, overseeing thirteen restaurants. He made the same pay as with the construction job but had more flexibility with his schedule and had the opportunity for higher pay with overtime work. Houston faced routine racism and discrimination from Mexican employees who didn’t think he should be a supervisor because he was a migrant. Ultimately, poor treatment led him to leave the manager position.

His next two jobs were in painting where he was paid $110-$140 per week, but after being accused of stealing on an airport remodeling project—an accusation his boss later revoked and apologized for after the culprit was caught—he left to find a new opportunity. He continued painting and has worked for the same boss for about one year earning $174 each week. He still faces racism from his Mexican colleagues, pushing him to the brink of quitting his job, but his boss attempts to provide some relief by sending him to work on his own, without partners, as a solution.

Throughout his constant hustle, Houston’s income is just enough to pay for rent and bills and whatever is left over goes to his children and mother in El Salvador. One day at work, Houston fell off a ladder and broke his back. He could not come up with the money to pay for the surgery he needed and was out of work for a month, leaving him and his wife scrambling to make ends meet.

An Example from a Less Welcoming Economy

Kenya

Rosine and her family were forced to flee the Democratic Republic of Congo due to violence. When her husband fell ill and passed away, Rosine and her six children relocated from Rwanda to Nairobi, where they stayed in a 6×3 room provided at the refugee receiving center upon arrival. She quickly began searching for work to provide for her family, finding a job at a restaurant through her church that paid $1.50 per day.

While her work at the restaurant improved the children’s health, two of whom were regularly sick due to malnutrition, it was still not enough to provide for all their basic needs. She was able to borrow a friend’s phone to reach out to her brother-in-law who, fortunately, was willing to send $250, which allowed Rosine to purchase other essentials like clothes for the children and a phone for herself. He continued to send $100 occasionally to help Rosine afford unexpected expenses like hospital bills or medicine for the children.

Rosine sought her own income to ensure consistent and sufficient finances for her family. She shared her idea of starting a restaurant with her in-laws who provided the startup capital of $4,500. With the help of a hired cook and her children, she is able to run the restaurant to meet her family’s basic needs. Each month, she puts away $100 as savings, but any additional money made goes toward her family’s expenses and running their restaurant. She also faces challenges with the bureaucracy involved in obtaining and maintaining her business license and handling the police who demand bribes to allow the business to operate that cause financial setbacks.

Ratcheting Phase

An Example from a Welcoming Economy

Mexico

Jerome was a college student who repaired cell phones in Haiti. Initially in Mexico, his wife paid for their rent from her salary so he could save up and get into an informal savings group called a “soldes.”

Eventually, he got the idea to start an electronics repair business. His mother, a Mexican coworker, a Haitian man, and another friend lent him money that he used to register his first repair shop. With the income he earned from the business, he was able to pay back each of these loans and was even able to return the favor for his former coworker. He was able to hire an employee to help at the shop and sends remittances back to Haiti where he supports both his family and his wife’s. He attributes his business’ success to his honesty and integrity in his work. Many clients come from referrals.

A little over a year and a half after starting his business, Jerome opened another electronic repair business for his wife, so they now have one business paying their monthly expenses, and the other allows them to save money. While their financial status has become more stable for now, Jerome points out that he and his family are still not fully integrated into their Mexican community where they face racism and exclusion.

Livelihood Chasing

An Example from a Less Welcoming Economy

Jordan

Abu Samer is a Syrian in Jordan and a positive deviant in the financial journey of migrants throughout the studies done in Jordan and beyond. Abu has a family of fifteen and managed to support them all by diversifying his income sources, relying on experience he’d honed in Syria. There, he owned a 50-seater bus that he drove for parliament and owned additional cars he rented out for supplementary income.

In Jordan, he began by renting mini-buses and trucks for a few months and saved up for a down payment of his own. He was then able to buy vehicles on installments, growing his assets. He then owned a 22-seater bus that he rented out to a school, providing Syrian school children with transportation, earning $2,500 each month. He was also able to purchase two more vehicles. He also partnered with a Jordanian to purchase a school that his two wives ran.

Despite building his own business, all assets he built were in the name of Jordanian partners due to legal restrictions that prohibit migrants from owning assets without a Jordanian business partner. This vulnerability came to the forefront several times. For example, one business partner cheated him, costing Abu two of the vehicles he’d purchased. In another instance, he was denounced to police on false changes, losing him stake in the school he owned. He was jailed on three occasions due to the informal nature of his business, once even deported to a camp at which point, he lost essential documentation.

Abu demonstrated strong entrepreneurial acumen building his assets and obtaining technical training that brought in income when assets were lost. Despite his ventures in Jordan and his investments in his children’s education, the limitations of legal ownership of his business stands are constant threats to anything he builds.

Please visit the Journeys Project at Tufts University for previous studies, ongoing research, videos, maps, and artwork on refugees and migrants in the Middle East and Mediterranean, Latin America, and Africa.

Contact: Kimberley.Wilson@tufts.edu