In this blog post, I will be providing neuro-scientific explanations of the processes of theatre performances that involve human actors. When performing, actors undergo an immense stress. It is almost as if in a given moment, one person (actor) becomes two (actor + character). And yet this statement seems too poetic… When it comes to discussing artistic talents, in particular the ability to transform into a character different that the self, there is often a hint of super-human, out-of-this-world abilities. The most brilliant actors are called mad geniuses; the talent itself is often referred to as a magic power. This mysterious attitude towards acting makes it hard for the young actors to believe in themselves, and often instead of trying again and again, they give up auditioning and learning because “there is always someone brilliant who will be better than everyone.” I find it important for both actors and academics to be reminded that there is no pure talent that can win all the producers and the directors of the world. There is also no inescapable mediocrity. Everyone is talented, but whether you can embrace your talent or not – is a question of practice. Demystification of emotions can be a powerful tool in establishing an understanding of acting that is both grounded in reality of the human nature and yet is nurtured by the infinite sources of creativity.

Hess defines emotions as “relatively short-duration intentional states that entrain changes in motor behavior, physiological changes, and cognitions” (p. 120). It is peculiar how the word “intentional” fits in this definition. Are all emotions intentional, even when they occur spontaneously and have no apparent reason? Can it be that intentionality is an inevitable aspect of emotions, because ultimately even if one is not aware of one’s emotions and their sources, one initiates emotional reactions and expressions? The source of emotions is the person him/herself, so does it make the emotions intentional? The world of a dramatic piece is where emotions are definitely intentional. However, there is a chance that in achieving the incredible level of acting brilliancy, a performer can fully internalize all the emotions and thoughts of the character, and the artificiality will dissolve… The glorious state of flow will be reached, and then all the Oscars and the Tonys will be received… But before we get to this exciting part of acting, let’s start with a brief overview.

Below is the scheme of the acting process, in my own words:

Acquisition of the dramatic material (familiarization, first emotional reactions, basic structural and dramaturgical analysis)

Memorization (text, movement); internalization (emotions, traits)

Channeling (emotional and physical aspects of the character become the second nature to the actor when he/she rehearses and/or performs)

There are several components of any human dramatic performance: text (script), physical appearance, voice, emotions and movement.

Below I will briefly indicate the questions that interest me the most in exploring the brain activity involved in emotional and motor functions during theatrical performances.

Emotions.

In simple terms, acting involves two types of emotions: 1. self-stimulated emotions and feelings, triggered and/or motivated by the given circumstances of the play; 2. emotions that represent reactions to other actors/characters’ behavior and /or actions, emotions, words, silences, etc.

Emotional memory and cognitive memory definitely collaborate during the process of the script acquisition. First, the character and the story appear as emotional stimuli. Through familiarizing oneself with the events of a play, an actor reacts to the story, and then gradually starts internalizing both the reactions and the reflections about a given character. In her study of the amygdala and the hippocampus, Phelps suggests that the amygdala receives information about the emotional significance of a stimulus very early in stimulus processing. It can result in enhanced perceptual encoding for emotional events. “By influencing perception and attention, the amygdala can alter the encoding of hippocampal-dependent, episodic memory, such that emotional events receive priority”. (Phelps, p. 200) Therefore, both self-stimulated emotions and reactions are being memorized in complex with the script.

Movement.

It is safe to say that most theatre pieces that use human actors also involve physical movement. In the traditional realistic acting that most non-professional audiences are familiar with actors should follow the stage directions (usually pre-existing, within the text of a play). Therefore, often the movements are learned just like the lines are. The actor may invent and implement certain movements as well, which would be motivated and justified by the character’s behavior.

Once all the required steps towards the good acting have been taken, the actor finds him/herself on a risky road to perfection. Its neuroscientific name is the flow state.

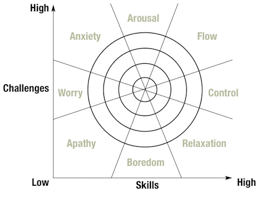

Media Neuroscience Lab web-resource provides the following illustration of the flow state:

“Synchronization Theory of Flow”, http://www.medianeuroscience.org/sync_theory

Dietrich (2004) suggests that “the flow state is a period during which a highly practiced skill represented in the implicit systems knowledge base is implemented without interference from the explicit system.” (p. 746) Hypofrontality is, however, required prior to the experience of flow, since it temporarily suppresses the analytical and meta-conscious capacities of the explicit system. In her research Dietrich unpacks very nicely the concepts of explicit vs. implicit systems, as well as another dual system of the information processing: emotional and cognitive (Dietrich, p. 748). The explicit system is conscious, and involves conscious learning, while the implicit system is more automatic, subconscious. The explicit system functions in prefrontal regions (DLPFC) and involves working memory (p. 751). However, if a certain skill is acquired and then practiced intensely and regularly, it transforms from explicitly learned to implicitly experienced. The basal ganglia have been indicated as ‘the home’ of the implicit system: it processes procedural memory and multi-dimensional tasks.

If we look at the art of acting through this framework we can notice how it coincides with many common acting techniques. Indeed, the first level of learning of any dramatic material involves conscious approach, mental analysis, high level of focus and awareness. But once the script of a role is memorized, once there is no need for an actor to worry about the words, or the movements, or getting used to the uncomfortable costume, colored contact lenses or a thick layer of makeup, – then the real transformation takes place. An actor transcends the ordinary, the earthly details of his character’s behavior, and starts to simply live in the role, or let the role live through him/her. And while this sounds poetic and supernatural, neuroscientists have a term for this state: Flow. The main mystery about this state is how it feels effortless and yet results in high-quality performances. Dietrich suggests that the information processing efficiency of the implicit system becomes combined with experience-based increase in (reflexive) flexibility and thus results in the effortlessness characteristic of the flow state (p. 756). The concept of flow becomes more familiar to some theatre practitioners as well: in his blog, acting coach Mark Westbrook explicitly states that the nine elements of the flow coincide with objectives of any good actor:

- There are clear goals every step of the way.

- There is immediate feedback to one’s actions.

- There is a balance between challenges and skills.

- Action and awareness are merged.

- Distractions are excluded from consciousness.

- There is no worry of failure.

- Self-consciousness disappears.

- The sense of time becomes distorted.

- The activity becomes an end in itself.

http://actingcoachscotland.co.uk/2014/08/flow-why-we-do-what-we-do/

When a performance is believable to the audience it often means that the performer may have achieved a trance-like state (Drinko, 2013) and if after the performance he/she is asked about his/her experience, the actor would respond something along the lines of “I don’t remember, I was not myself, I blanked, I was fully immersed”. The most recent example from the mainstream Broadway culture is Neil Patrick Harris (NPH) in Hedwig and the Angry Inch, the role in which NPH was known to transcend the self, to be in a trance for the most part of every show, and afterwards he many times confessed that he did not remember anything. We can assume that he had reached the state of flow.

And yet, everything has a price. Flow necessitates a state of “transient hypofrontality” which includes a certain degree of inhibition of the cognitive function. (Dietrich, p. 759)

In other words, for a performer the best flow state also means the lack of all external distractions, a complete immersion in the dramatic material. Which certainly gives very satisfying acting results, but can also tempt to take extra steps to achieve the flow. Artists are known for issues with substance abuse, as well as creative blocks caused by withdrawal. Maybe there is a less dangerous and more legal way to reach the flow state ? And then, mysterious “gifts” such as genius, talent, inspiration could be demystified, but also internalized as something achievable for anyone who is willing to put effort and time into practice …

Resources:

Dietrich, A. (2004). Neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the experience of flow. Consciousness and Cognition, 13(4), 746-761.

Drinko, C. (2013). Theatrical improvisation, consciousness, and cognition. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hess, U., & Thibault, P. (2009). Darwin and emotion expression. American Psychologist, 64(2), 120.

Phelps, E. A. (2004). Human emotion and memory: interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current opinion in neurobiology, 14(2), 198-202.

Great internet resource (brain structure and functions): http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/a/a_04/a_04_cr/a_04_cr_peu/a_04_cr_peu.html

http://actingcoachscotland.co.uk/2014/08/flow-why-we-do-what-we-do/