by Lily, Civic Semester Participant

“The antithesis of [the] border is genuine connection with people”

Finn, No More Deaths Volunteer

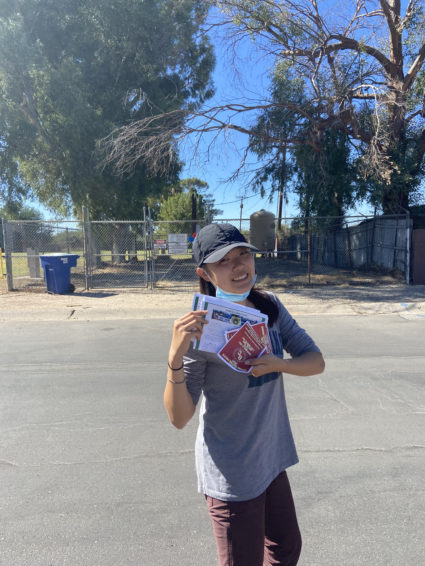

Saturday, November 6th, 2021 marks the Civic Semester’s second site visit in this portion of our trip in the Southern New Mexico and Arizona area. The cohort had another early morning (well worth it to see the beautiful sunrise on the mountains!) as we left Rodeo, New Mexico around 6:30 AM to make our way to the small town of Irovaca, Arizona, population size 700. There, we were introduced to No More Deaths volunteers, Finn, Hannah, Juliana and Ry (and last, but certainly not least, Finn’s dog June Bug!!) who started out the day by giving us a presentation on the historical and current context behind the U.S-Mexico Border Crisis. No More Deaths operates as a humanitarian-aid organization dedicated to ending death and suffering in the Mexico-US borderlands through a multitude of projects such as aid in the desert, search and rescue, and providing medical aid, food and water and other guidance. They also explained No More Death’s horizontal organizational structure, as opposed to the more traditional hierarchical distribution of power, something our cohort has been especially interested in learning about in terms of community activism. Acknowledging the increased time it takes to make decisions—everyone must reach consensus!—it allows NMD liberty in freeing their minds to more radical ideas of organizing and creates a capacity for each individual to continuously reevaluate their reason and motivation for doing this work, as well as holding themselves accountable to each other and their mission. Additionally, it means a constant need to improve on the organization’s communications, collaboration and transparency—something the Civic Semester is working on as well!

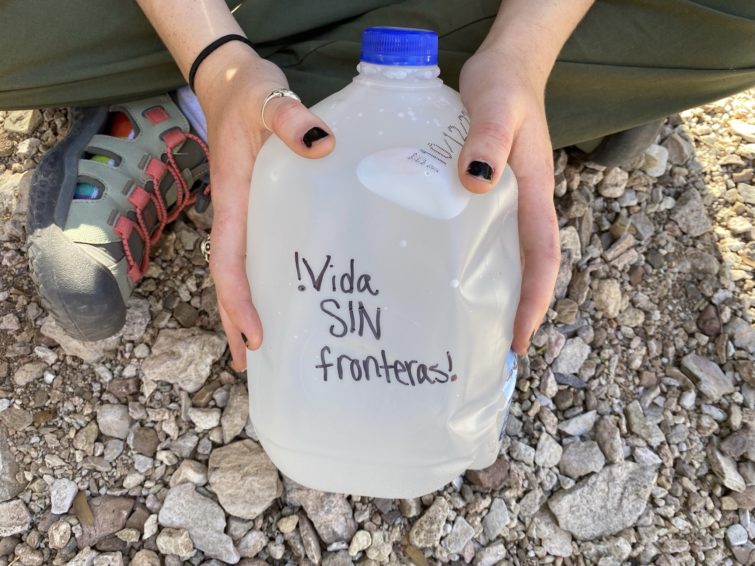

While sitting in the extreme, desolating heat of the Sonoran Desert during this conversation, our cohort was hit by the immensity and gravity of such a complex issue like the Border Wall, the economic, political, historic and ethical crises that it encompasses, and the inhumanity and violence that those who travel between must endure. After our discussion, we went on a water drop where volunteers hike along trails and leave water, food, blankets and other supplies for those traveling through the desert. Heavy in our backpacks were an assortment of beans, gallons of water, snacks and blankets as we started our long trek toward the water drop site. Working our way through lots of thorny brush, rocky inclines, and the intense heat of the sun, we successfully made it to the site with June Bug leading the way! During our strenuous hike, we were once again hit with the realization of the truly impossible and extremely dangerous task of walking across the desert for survival, shelter, and safety and the weight of the situation and work we were doing.

“How do you reconcile with the work that you are doing on a day-to-day basis with an issue that extends beyond any individual, any organization, any nation-state?” In other words, “ Where do you find the strength and hope within this work?” This question sat heavy on my mind, our discussion and the day.

“ …This work is for my ancestors, and for my future ancestors regardless of what happens, and what is happening now”

Ry, NMD Volunteer

“ The antithesis of the border is genuine connection with people.”

Finn, NMD Volunteer

These responses, coupled with the clear, vulnerable, and beautiful relationships that these individuals held for each other and for the community of Irovaca, made clear the dedication, perseverance and determination each of them possessed to maintain an internal strength and hope. A hope that was profoundly inspiring to our own conversations of this struggle to tackle these anchored, institutional powers. As Finn reminded us, as many bad days as there are, it is vital to remember the really, really good days and the people you meet and create genuine connection with. And our visit with No Mas Muertes was a really, really good day to say at the very least. We will forever be grateful to those at No More Deaths and their vulnerability, transparency, and the opportunity to work with them.

With all our love and gratitude to NMD,

Tufts Civic Semester 2021

Originally posted here.