By Dani Steinberg

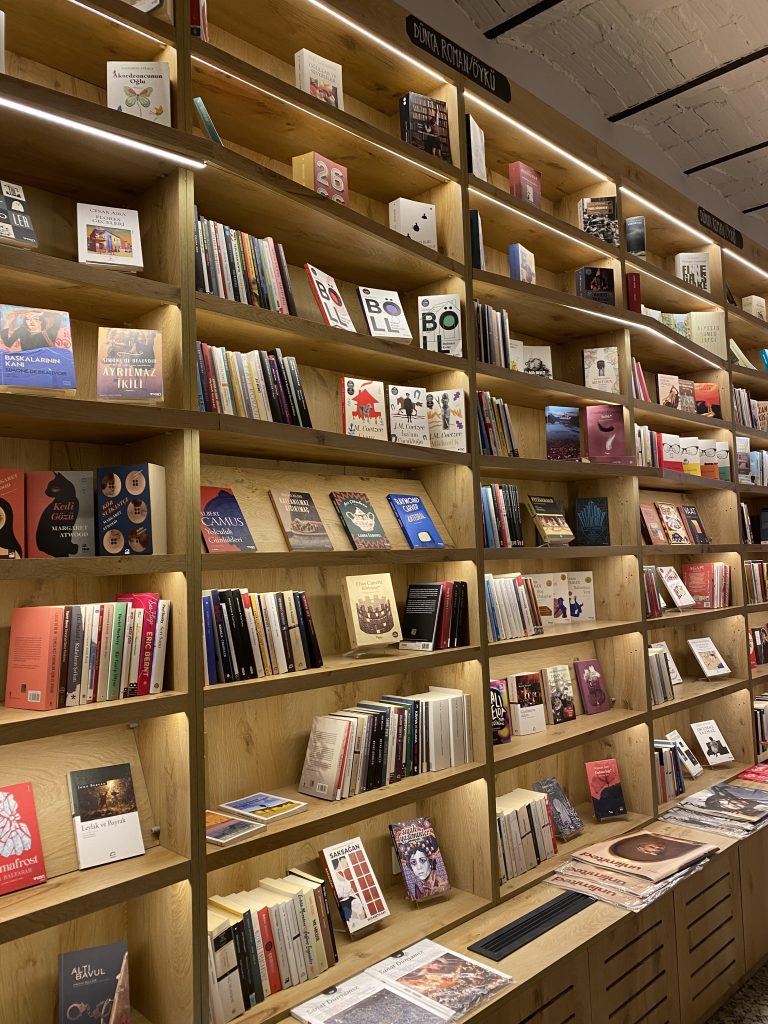

On one of the first days I was in Istanbul, I was exploring the neighborhood around our accommodations and I happened to pass a really neat book store. There were two small tables on the outside of the bookstore and when I peered through the windows, I saw the shelves were lined with feminist novels and art books in many different of languages. Since my project centers around art books and literature in Istanbul, I became very intrigued.

After this first encounter, I knew I would have to come back to learn more about this interesting institution. This bookstore, Frankestayn Kitabevi, as I would later learn, was opened by Asye Tumerkan in 2022 when she realized there was no place in Istanbul that carried novels centered around feminism and queerness. As one of the only bookstores in Turkey, and definitely Istanbul, that centers around selling books related to feminist and queer literature, Frankestayn connects writers and readers with books they might not have otherwise encountered. Asye told me during our interview that one of the most important parts of opening this bookstore was that it was a place not only for people to be exposed to new and radical forms of literature, but that the bookstore could host events by and for the queer community of Istanbul.

In comparison to the rest of Turkey, Istanbul is a relatively safe place to be queer and feminist, however, there exist very few places that allow for queerness and community to be built around literature in such a public and open way. Through poetry readings, open mic nights, book clubs, and other events, Frankestayn Kitabevi helps the queer community of Istanbul have a place they can meet gather and learn together. It is also one of the only places in Istanbul where one can buy small-print run artist books by various local independent publishers and artists.

Being able to interview Asye and learn more about her experiences and life within the publishing realm helped me learn more about art, literature, publishing, and community in Istanbul in a way that was very nuanced.