By Gabriela Perez

My parents are disconnected from their indigenous roots, but the trips to my parents’ childhood homes and seeing my grandparents’ and great grandparents’ portraits make our indigenous roots undeniable. I find it greatly important to preserve pre-Hispanic ancestry, especially because I am so disconnected. That is why when I saw that LAC was going to Mexico City (CDMX) for personal investigations, I leaped at the opportunity.

Mexico City is the largest city in North America, so I knew it would be a hub of resources and information that could kickstart my investigations. Although CDMX is not the region with the largest Mexican indigenous population presence (which would be Oaxaca and Yucatán), there is an astonishing presence of indigenous cultures in and around the city. There are 55 indigenous languages spoken in the city alone.

When comparing the prevalence of indigenous culture in Mexico to the United States, I sat in awe at the difference in the preservation of languages, with 68 live indigenous Mexican language groups which consist of over 300 distinct linguistic variants. This is especially critical when considering how vital language is to culture. I felt an immense need to understand the reasons behind this wonderful preservation of languages and what makes Mexico stand out in such a unique manner. I was particularly interested in understanding the role of institutions with the preservation and attitudes from indigenous and non indigenous individuals towards indigenous cultures.

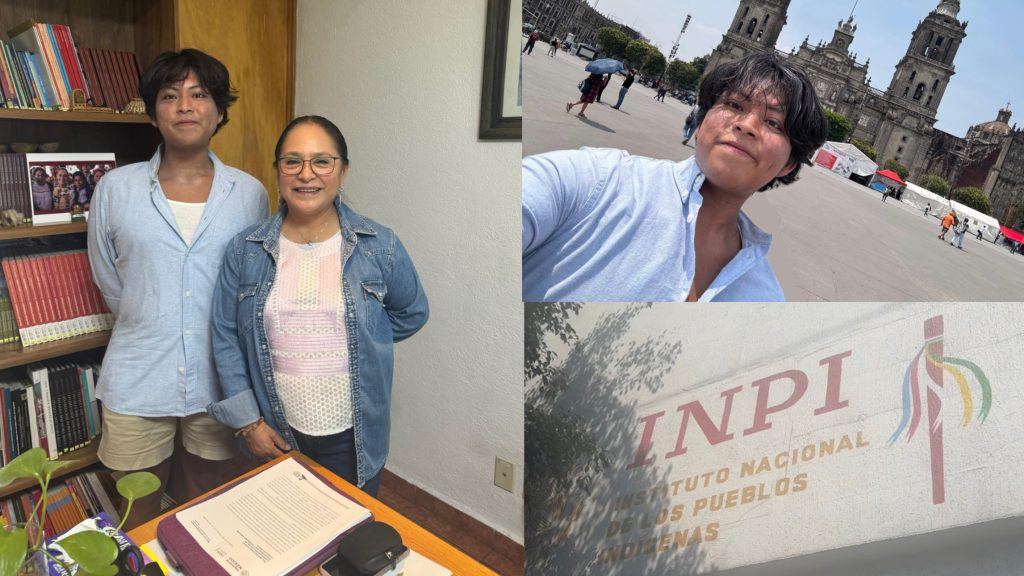

I spoke with a professor who works in the indigenous education department at the National Pedagogical University (UPN) in CDMX to gather more insight on what space indigeneity holds in Mexico. UPN is a university that dedicates itself to teaching others how to teach. The indigenous education department, in particular, works towards creating a space/context where others feel compelled to speak the language. She explained to me that this program is not linguistically focused but rather keen on getting the indigenous languages “out there” because the prevalence of the languages is in a state of emergency. More work has been done to maintain tangible indigenous cultural manifestations such as embroidery than intangible manifestations such as language because it can be commercialized. So, more work still has to be done to preserve indigenous intangible culture and to gain more support from institutions such as the university and government. I will continue talking to individuals from other institutions such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI) to gather a fuller idea of the situation of indigenous cultural preservation efforts in and around Mexico City.

Learning about the place indigenous presence holds in a pluricultural country like Mexico has taught me how important it is to maintain a sense of self regardless of the more dominant society it may preside in. It also highlights the importance of making space for one’s culture.