Humans of Sackler, 23 March 2017

Patrick Davis, Neuroscience, Fifth-Year M.D./Ph.D. Student: “I’ve been Accused of being a Science Robot”

For this issue of Humans of Sackler, I had the opportunity to sit down with Patrick Davis, an M.D./Ph.D. student in the Neuroscience program. Although I see medical students coming and going around Sackler every day, I confess I haven’t gotten to know many of them – or much at all about the medical school curriculum. So it was a great pleasure to learn more about this from somebody who is as passionate about medicine as he is about science research; Patrick and I had a particularly engrossing conversation about the differences between these two kinds of higher education, and I hope you, dear reader, enjoy and benefit from it as much as I did!

AH: How did you become interested in studying science?

PD: I had a physics teacher in 11th and 12th grade – Marty Baumberger – who was just the best teacher ever. He got me so into physics that I started a Theoretical Physics group at Chestnut Hill Academy… I went to Brown University as a physics major. I loved the open curriculum, but I was a terrible student. I didn’t do well my first year, so I switched to an economics major for about a year, and that was completely unfulfilling. Eventually I came to my senses and switched to biology… The thing about Brown: it’s chaos. There are no required classes, so you just mix and match and do whatever. There are requirements for your major, but you could theoretically never take a math class if you never wanted to. What happened to me was the best-case scenario: the first year and a half made me a more dedicated student. I learned that if I’m not doing something I really want to do then I’m going to be lazy, and if I don’t work hard then I’m not going to do well.

AH: What was your first experience with neuroscience research?

PD: When I graduated from Brown, I didn’t know right away that I wanted to do med school or neuroscience. I ended up working at Jeff Macklis’s lab at Mass General Hospital for two years after college, and that was my first real exposure to neuroscience. Jeff made his name with a series of studies on induction of neurogenesis in the neocortex. I met Alex Poulopoulos there, who has been a mentor ever since, and a very good friend. I would credit Alex almost entirely with piquing my interest in neuroscience, but also with my development as a scientist. I love to come up with an idea, test it, go through the whole process myself, interpret my own data, talk to other people about their data – I like the actual scientific process. Alex just started his own lab at University of Maryland School of Medicine; anybody reading this, please apply to his lab! You could not ask for a better person to work for. He’s interested in how neural circuits self-organize, which is extremely interesting to me as well.

AH: Why did you choose the M.D./Ph.D. path and how have your medical and scientific training differed?

PD: I could never be just an M.D. because I love science too much. The fundamental quality of a scientist is curiosity; medicine is more like service and helping people, curiosity about the people themselves, empathy. The preclinical years are a lot of memorization, but once you get into the hospital, it’s more like an apprenticeship. You’re learning how to do the day-to-day things that a doctor does: how to walk through clinical decision-making, interview a patient, present that information to other doctors, how to work with your hands if you’re doing a surgery rotation… Because medicine is an applied science, the goal there is all oriented around the health of the patient; I don’t think that’s really what science is about. For a long time, medicine has been done in a very parochial way: people in this hospital do it this way, people in another hospital do it another way. Evidence-based medicine still gets a lot of pushback. Take stenting for example: doing a coronary artery stent for someone with angina. About half of the stents in this country are done for stable angina – chest pain when you exercise, but not an acute threat to your health – and it’s now been shown over and over again that that is no better, and possibly worse, than just giving them statins and blood pressure reduction medication and telling them to eat their vegetables and exercise a little bit. It’s because doctors think in terms of, ‘I see it happen, it intuitively makes a lot more sense to me, so it must be this.’ Of course the lines are blurred in real life, but a true scientist would say, ‘We have to trust the evidence, why don’t we look at what’s causing the increased risk of doing the stent, or why do statins work?’ The curiosity that is absolutely necessary to be a good scientist is not necessary to be a good doctor… The types of mind that are selected for by these two professions are almost non-overlapping, they’re completely different.

AH: What do you like to do when you’re not studying medicine or neuroscience, and how do you find the time and energy to do it all?

PD: I love to teach, I really like being in the didactic role and seeing people learn and discover things for themselves. I tutor for the MCAT, I used to tutor for the SAT, I’ve volunteered for things like middle school science fair mentoring and the Brain Bee. These kids in the Brain Bee were extremely impressive; they knew more facts for this test than I would have! Thomas Papouin and I also started a class trying to teach grad students the basics of the scientific method. There’s a whole rich history of how to think formally and scientifically; and the more aware you are of it and the more you practice it – like by applying these things to your own rotation project or qualifying exam – the better you get at it. The notion that, by just reading papers, this will happen – for some people, maybe it will, but the purpose of the program is to maximize the probability of this happening for everybody… I’ve been accused of being a science robot: the joke between Alex Jones and me is that when I get home, I have a scotch and read PubMed… The M.D./Ph.D.s that I’ve spoken to, the ones that succeed, are recharging one half of their brain while the other one works. Like a shark, like a science shark!

AH: Have you had many chances to travel outside of the U.S.?

PD: I’ve traveled through Europe a bit, I’ve been to Peru, Brazil… I was in Berlin at one point, and I decided to just hop on a train and go to Prague. I spent two full days and a night there, and it was awesome. Most of the people spoke English at tourist-type places, but it was fun to walk around, take pictures, be completely by myself… I had a Cormac McCarthy book called “All the Pretty Horses”, and it was nice just being on the train, reading or watching the sites, then walking around the city and going to a café for a coffee or beer. I don’t know much else about Prague, but aesthetically, I can’t imagine a prettier city. Part of why I enjoyed the city so much was because I didn’t expect it to be that way: of course when you go to Rome, you know that one of the greatest civilizations existed here and that every step you take is rich with history, but I didn’t expect this in Prague.

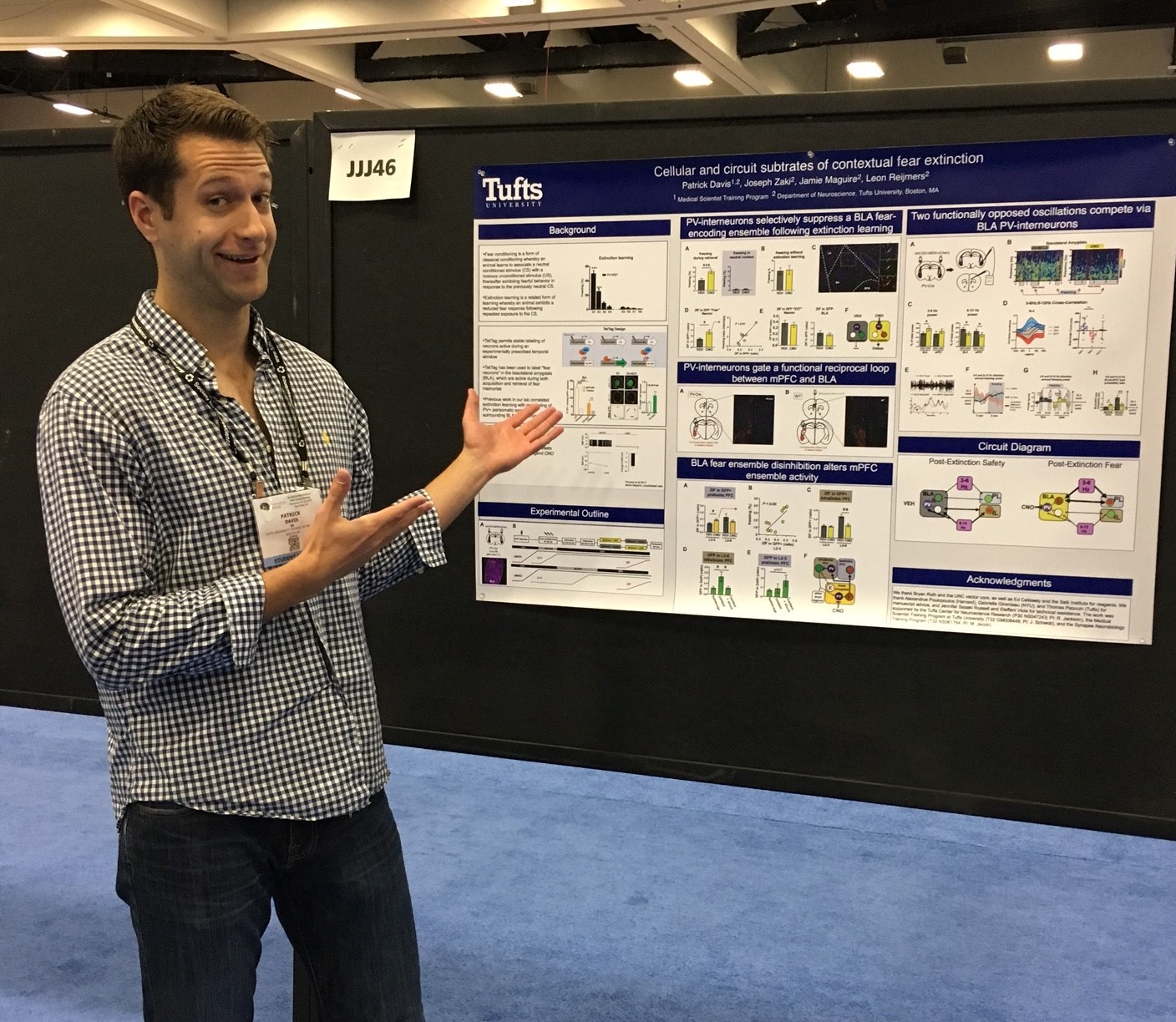

AH: What topic have you studied for your thesis work?

PD: Under Leon Reijmers’ mentorship, I’m trying to figure out how ‘extinction learning’ happens in the brain: it’s a medically-relevant type of learning that underlies treatment for psychiatric disorders like PTSD. In extinction learning, the patient repeatedly gets exposed to the thing they’re afraid of, you gradually increase the ‘stimulus intensity’, and they learn that it’s safe. So for example, if they’re afraid of spiders, you would show them a picture of a spider at first, then maybe have them in a room where there’s a spider in a corner, then work your way up to having them handle a spider. What I’ve found is that there’s a particular cell type in the amygdala – the parvalbumin interneuron – which acts a critical hub for this kind of learning: if you silence these cells, then you shut down the process of extinction learning. Now I’m using that finding as a jumping-off point to really figure out what’s going on. I’m manipulating parvalbumin interneurons with different frequencies of stimulation and seeing how the amygdala – and the rest of the brain – responds to that. It looks like I can ‘toggle’ the fear state up or down just by controlling this specific type of neuron!

AH: Where do you see the field of neuroscience heading in the near future?

PD: I think that we have tools in neuroscience that 15 years ago, you couldn’t have even fathomed. Not just optogenetics, but recording techniques, chemogenetics, optical electrophysiology, simultaneous local field potentials with single units, closed loop systems… The engineers like Ed Boyden have done us a great favor. But now it’s time for us to step up. I think that in the next 2, 5, 10, 15 years there are going to be many, many discoveries that are really going to blow things open. Once we fall out of love with the mere application of modern tools to hypotheses we already kind of assumed to be true, then we’re going to ask the question: how? You have to record neurons’ endogenous activity, then do experiments that are really informative about what’s going on. In neuroscience, because we have these techniques, we can start asking this kind of question.