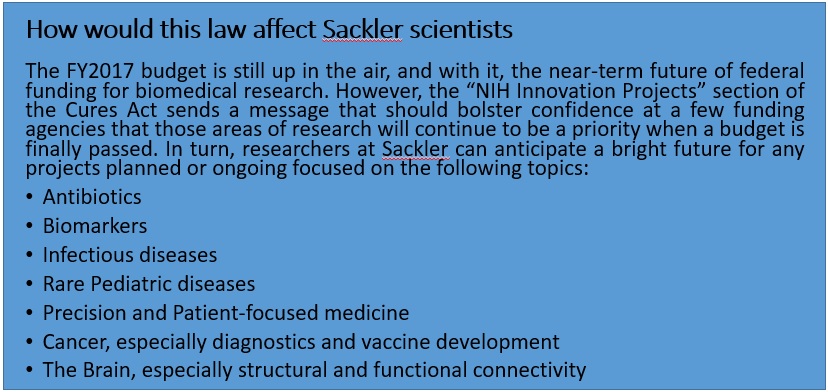

The effects of the March and the outpouring of support for scientific research and evidence-based policymaking are already showing, as exemplified by the increase in NIH funding approved by the Congress instead of the Trump administration’s proposed cuts. However, this should not make us complacent in our demands. The EPA’s scientific advisory board is being replaced by representatives of agencies it is meant to regulate, climate change action is still being hindered and the environment is increasingly threatened, and the anti-vaxxers just succeeded in invoking an outbreak of measles in Minnesota. As Dr. Harris Berman, along with the deans of other medical schools in Boston, recently wrote “We must harness this energy and ensure that the March for Science on Saturday marks the beginning of closing the rift that got us here in the first place”, we should also ensure that this march becomes the global movement it is meant to be. The enthusiasm & sense of urgency that brought out the scientists out on the streets on April 22 should be harnessed to battle the anti-science hysteria currently spreading across the nation. The only way to do it would be to not isolate, but engage the public, to whom we have a responsibility for putting their faith in us, in meaningful ways to improve science literacy through relevant communication. Here we present some additional resources for you to get engaged in science activism after the March:

- Communicate Your Science – Increasing visibility of scientists and science among the general public would help to shore popular support for scientific research. The #ActualLivingScientist campaign on social media helped dispel the alienation between the scientific community and the people who support their work. Share the importance of your work by writing or speaking about it online or offline. For example, check out The People’s Science’s new initiative, The Field Project, where researchers are encouraged to write a brief summary of their work for the “broadest possible audience”. Talk about your work and how you got into scientific research through our “Humans of Sackler”. Or even better, write for us if you want to practice your writing and communicating skills. Visibility Matters!

- Volunteer in Science Outreach – The greater Boston area provides ample opportunities for science outreach programs, especially with large-scale events like Cambridge Science Festival. On a smaller scale, you can volunteer for the BIOBUGS, the Brain Bee, the annual mentoring opportunity at Josiah Quincy Upper School and more. Keep an eye out for emails re: these events & more from the Sackler Graduate Student Council.

- Engage in Policy Action – Since the election, scientists have started to take on political action themselves. One such group is 314 action, who seeks to elect “more leaders to the U.S. Senate, House, State Executive & Legislative offices who come from STEM backgrounds”. The Union of Concerned Scientists, who have been fighting for evidence-based policy to solve social & environmental problems since 1969, hosts an advocacy resource where you can learn how to take action with or without getting involved with the organization. If you would like to write about policy, this writing program by Rescuing Biomedical Research can be your first foray into that world. You can also get involved with the new student organization at Sackler, Scientists Promoting INclusive Excellence #@ Sackler (SPINES), which seeks to increase visibility of minority scientists among other goals.

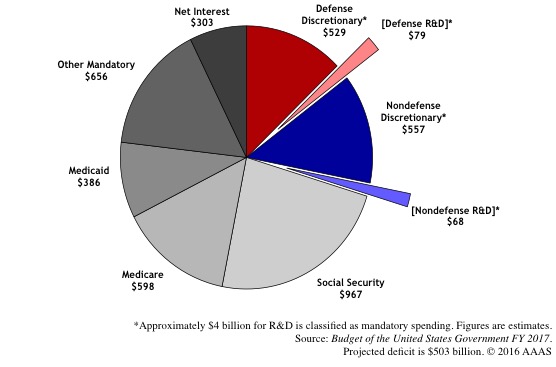

- Educate Yourself – If you are not sure on how best to participate in science activism, you can start by learning. Follow the official March for Science blog to learn how the movement is advancing. Check out this online class being offered by faculty from University of Michigan on how to “more effectively discuss knowledge”. Get involved with the Emerson Science Communication Collaborative between Emerson media students and Sackler students. For an even extensive gamut of resources, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) has an online toolkit for you to start getting involved!

If you know of any other organizations or groups involved in science literacy, education, outreach & communication, please leave us a comment below!