Churchill in 1940: The Individual in History

by John LaLime

Mentor: Elizabeth Foster, History; Funding Source: Marie R. Evans Endowed Summer Scholars Fund

On May 10th, 1940, Germany launched its long-planned invasion of France and the Low Countries. On the same day, Winston Churchill became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Churchill was only tepidly accepted by his Conservative peers to lead the country, especially with his complicated record of military leadership from the first World War. Meanwhile, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), with some 300,000 young men, was in mainland Europe to assist the French, Belgians, and Dutch. In just a few weeks, by May 24th, the BEF was cornered, with their backs to sea with the Germans closing in. The French army had lost the north of France, while Belgium and the Netherlands had fallen entirely. In London, certain voices, namely that of Lord Halifax, the powerful Foreign Secretary, began speaking of a negotiated settlement with the Nazis as a way to end the war and save the BEF. In meetings of the War Cabinet, the executive committee directing the British war effort, Halifax and others seemingly had Churchill cornered – the only sensible solution was to make peace with Hitler to save hundreds of thousands of British men and, potentially, save Britain itself.

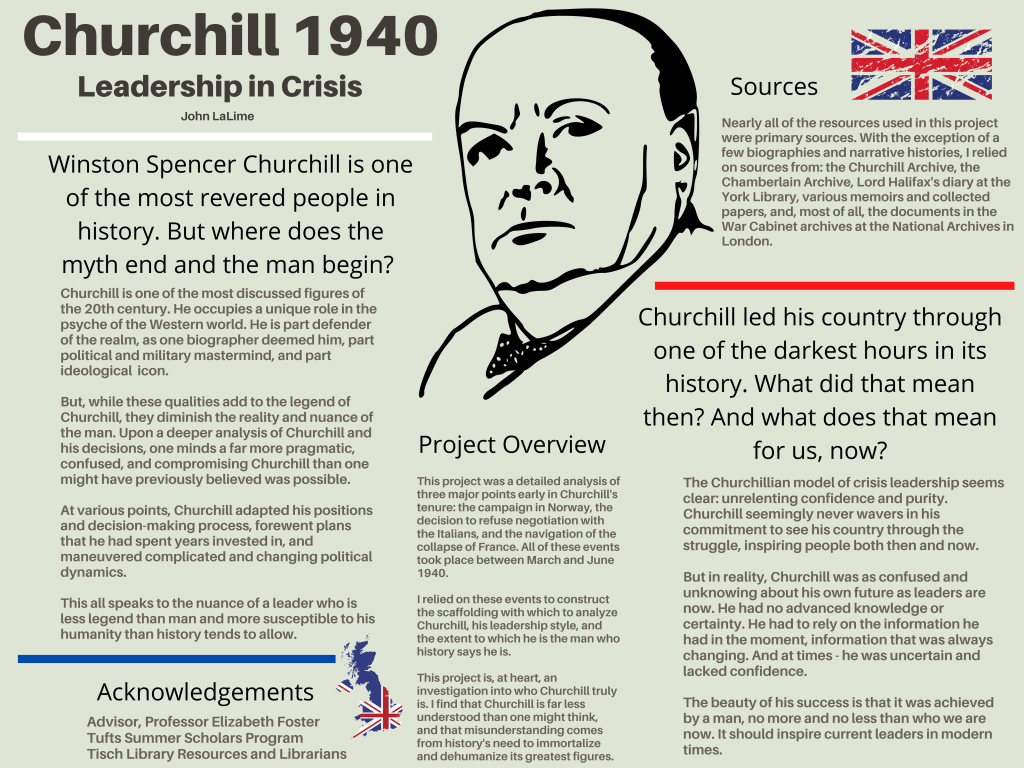

This dramatic moment is the stuff of myth and legend. Churchill has attained immortal status as the man who defiantly faced off Hitler – and won. But the real Churchill is a very different man from the legend that we know now. To unpack Churchill, and the events that helped to shape this point in history, I focused on three major moments: the military campaign in Norway in March and April, the decision to avoid negotiation with the Italians in May, and the ultimate collapse of French resistance in June. I chose these moments because they all showcased the development of Churchill as a leader, as well as illuminating some of his characteristics that are lesser known and appreciated.

The mythical Churchill is an idealistic, emotion-driven gambler. This legend leaves no room for Churchill’s humanness nor does it leave room for a reasoned, logical version of the man. The three contextual moments that I chose to analyze help to reintroduce Churchill’s complication and nuance. They help to show the uncertainty of the situation, and thus the uncertainty of the men who were attempting to navigate it. But beyond that, the day to day decision making process helps to show a different version of Churchill, one who is dominated by his pragmatism and ability to adapt and compromise. Instead of only seeing Churchill in grand, dramatic fashion, this project helps to show a more simplified Churchill. Namely, how he reacts to the minute details in Cabinet, differing points of view from his ministers, and the constant flow of bad military news from the front.

Through the use of primary sources, including War Cabinet documents and personal memoirs and diaries, I find a pragmatic, logical, and reasoned Churchill. I find a Churchill who sees the war in a different way, not as another European conflict to be won or lost, but as an ideological struggle; a struggle that could only be won by resisting the urge to appease Nazism and fascism. I also find a Churchill who is at times confused, uncertain, and indecisive – a far cry from the Churchill of historical legend. There is the suggestion that this different view of Churchill somehow limits his historical power or status. I disagree. In fact, I believe that my findings on Churchill actually enhance his historical stature. All too often, our historical figures and heroes are dehumanized in our attempt to honor them. But what makes our history so powerful is that it belongs to us, achieved by people who are not unlike ourselves. Churchill’s leadership in his crisis was not unique, it was not certain, it was not ordained. It was earned, in a complicated and nuanced way, by a man who was all together confident, charismatic, but also uncertain, cautious, and pragmatic. It gives us hope that if past generations could face down the evils of tyranny, fascism, and Nazism, then our generation can do it today.

Hi John, I really admired your project. You emphasized examples of Churchill’s indecision. Does this mean that he waffled once he had already made a decision or that he was indecisive in the period of time before he made up his mind? That would seem to me to be an important distinction to make.

This is really cool! I like how you present your findings in a sequential, almost narrative form; I think it provides a readability that a lot of research posters lack. I’ll definitely look at Churchill with a more nuanced lens from now on!

This is such an interesting project! It’s so impressive that you’ve been able to get so much of this information from primary sources and are focusing on such a specific point in Churchill’s life– it’s already so detailed and I am excited to see how it turns out.