Leir Migration Monitor – October 2022

Last week marked Financial Inclusion Week’s 8th convening. This year focused on Inclusive Growth in a Digital Era, underscoring the duality of tech-enabled financial services as both a mitigator and catalyst of inequality. This month, we explore approaches to migrants’ financial inclusion, ranging from the essential elements of enabling environments to the usefulness of “migrant tech.”

In this month’s edition:

- Analysis: When does financial inclusion matter for migrants?

- Launch of Leir’s newest program, Digital Portfolios of the Poor

- Senior Fellow Profile: Jayshree Venkatesan, Research Director at the Center for Financial Inclusion

- Dispatches from a financial coach: the economic empowerment of immigrants

- The “app-ification” of migration: are niche tech products useful?

.

.

When does financial inclusion matter for migrants?

Kim Wilson, Principal Investigator, Journeys Project

Last week, the Center for Financial Inclusion observed Financial Inclusion Week. To acknowledge the week and the work of a very able alum (more in Jayshree’s spotlight below), we’re reflecting on our research about financial inclusion in economies of displacement. Our findings are simple but often overlooked: without enabling economic policies for migrants—or at least impartial ones that don’t preclude migrants from the market—meaningful financial inclusion is rarely achieved.

In 2020, Fletcher hosted a conference where we presented the findings of a longitudinal study. Over the course of eighteen months, we interviewed 428 refugees, migrants, and hosts in five research sites: Amman, Jordan; Nairobi, Kenya; Tijuana, Mexico; and Kampala and Bidibidi, Uganda.

Our key findings showed that financial services, except for remittance services, were of little use to refugees and migrants.

Without permission to work or open a business, there was little left over to save and any borrowing that took place was from local shops, not from formal financial service providers.

The exceptions were in Tijuana, Mexico and Kampala, Uganda. In Mexico, migrants and refugees who worked in factories needed bank accounts to receive a salary. And in Kampala, Uganda, refugees successful at dodging local authorities were able to slowly build their livelihoods. However, these were the exceptions that proved the rule: they had licit means of earning an income and thus a bank account (Mexico) or a mobile money account (Kampala) was useful for capturing and storing those earnings.

Our concluding theory was that for financial services to be useful, foundational rights had to be in place. Lawful means of earning an income was the most crucial among these rights as was the ability to move about freely. In Jordan, work permits for Syrians were few and far between. And for other nationalities — Yemenis, Sudanese, and Iraqis — permits were only possible with passports, something none of our respondents had. In Kenya, refugees in Nairobi and in the camps had few ways to engage in a legal livelihood. The same was true in Bidibidi, Uganda, a settlement of around 270,000 people but with few means to earn a living. Brewing alcohol, farming basic crops, and selling food rations were the only livelihoods available and Village Savings and Loan Associations (informal folk banking systems) were the only relevant services.

An overarching observation was that the need for and use of financial services co-evolved with expanding livelihoods.

A new arrival might earn less than $1 a day sourced from charity or a meager wage for washing clothes. If they could find work, as was the case in Uganda and Mexico, a family might patch together a portfolio of income streams and slowly progress to the point where savings accumulated, and a bank or mobile money account would become useful.

However, it was not until we researched nearly 100 refugees and migrants in Colombia that we saw a true need for viable credit, meaning loans that could be used fruitfully and could be repaid on time. In Colombia, 2.5 million Venezuelan refugees are living among its various cities. We focused our interviews on those living in Cartagena, Santa Marta, and Medellín. The Colombian government has welcomed these refugees. They can apply for a ten-year residency visa (called a PPT) that affords several advantages: enrollment in the national health system, children’s enrollment in public elementary schools, and the right to work. Obtaining the visa required navigating a blizzard of red tape, and thus many refugees we spoke to did not yet have the visa in their possession. Despite this, local attitudes toward allowing Venezuelans to work were, if not welcoming, at least tolerant.

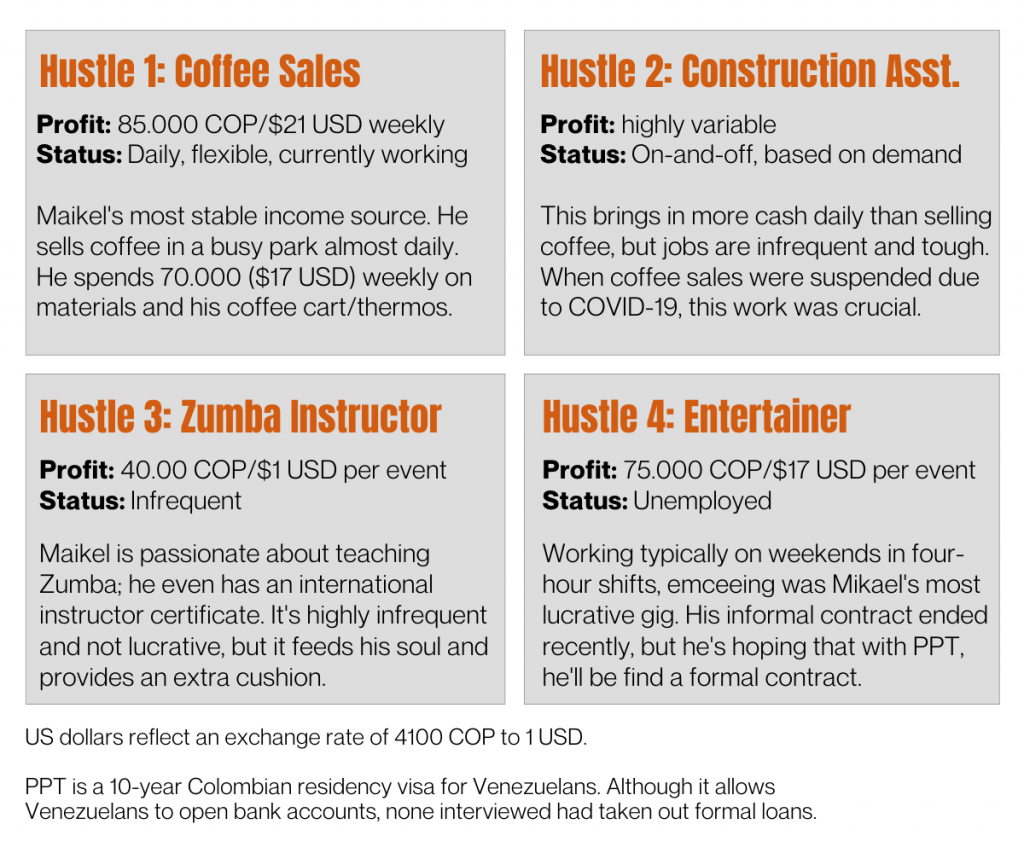

And this is where we saw the need for formal loans or credit from a microfinance institution. Let’s take Maikel as an example. He has woven together four side hustles to create a somewhat steady stream of household income. Between selling coffee in the park in the mornings, taking on sporadic construction work, holding Zumba classes, and emceeing children’s birthday parties, he brought in roughly $190.00 per month.

He was doing well enough to garner $320 in savings but burned through it when he booked few birthday parties and rain prevented his outdoor coffee sales and construction work. These events prompted Maikel to take out a loan from a prestadiario, a loan shark. He would have gladly borrowed from a microfinance institution, but such credit was not available to him, or to his knowledge, any other refugees. Although he recognized the 30% interest rate was steep and the procrustean payment terms too short (just a month), he’s found loan shark services useful in a pinch. He’d used prestadiarios on five occasions, each time borrowing about 100.000– 150.000 COP ($24–37 USD). When we interviewed Maikel, he had an outstanding loan of 150.000 COP ($37 USD), and he will need to pay back 220.000 COP ($54 USD) by the end of the month. We found other examples of people like Maikel, who had the permission and wherewithal to juggle multiple livelihoods, and who were borrowing from high-priced moneylenders.

Our findings in Colombia confirmed our theory that as livelihoods evolve so, too, does the need for financial services. This means providers might refrain from promoting financial services for the sake of inclusion and instead promote them where they are needed and can be used well.

.

.