Mobile Money and Financial Inclusion of Refugees in Jordan – Hope or Hype?

By Swati Mehta Dhawan and Hans-Martin Zademach

In recent years, but especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments worldwide have increased policy support for digital financial services with the aims of making payments more efficient and making banking safer while formalizing large informal sectors. To this end, payment fees have been waived and financial service providers have been allowed to onboard new customers remotely.

Mobile wallets are increasingly promoted for payments, including for social protection measures in times of crisis such as the COVID-19 lockdowns. Despite the increased support and use of mobile wallets, especially for aid and cash assistance disbursements, barriers to access persist for many refugee populations in Jordan.

The rise of mobile wallets in Jordan during Covid-19

In Jordan, the government has promoted the use of electronic financial accounts through mobile wallets. These “m-wallets” are digital reservoirs on mobile phones where users can store money that they can later release as payments, remittances, or cash withdrawals. In 2017, the National Financial Inclusion Strategy promoted m-wallets as the primary tool for the financial inclusion of low-income Jordanians and refugees. However, until recently, more specifically before the pandemic, m-wallets were far from mainstream. When we conducted our first round of interviews in 2019, almost none of our participants knew about m-wallets.

However, things have changed quite dramatically since then. As the country went into a lockdown due to COVID-19, the Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) took prompt measures to allow online registration and electronic know your customer (KYC) verification for m-wallets. CBJ partnered with the National Aid Fund (NAF) and Social Security Corporation (SSC) to distribute aid to vulnerable Jordanians through m-wallets. This was supported by major efforts to raise awareness through social media platforms and television.

Between March and July 2020, the country saw a 40% increase in the number of registered wallets, with more than one million wallets registered (and 1.47 million as of May 2021), or 10% of the country’s population. The increase in the transactions, both by volume and value, has been impressive as well. Most of this use is attributed to the capture of salaries and aid distributed through NAF and SSC, which means users’ primary motivation to use their m-wallets is to make cash withdrawals. Notable in the increase of m-wallet usage for NAF and SSC distributions is that such assistance is received by the “head of household” which is a male in the vast majority of cases, resulting in a massive gender gap in the receipt of assistance and likewise, the ownership and use of m-wallets.

A recent national survey found other use cases gaining popularity as well, such as paying phone bills or airtime top-ups, person-to-person transfers, paying for utilities, and even making other online purchases. Still, the survey confirmed that most Jordanian users opened their m-wallets to receive government aid.

The use of mobile wallets by refugees in Jordan

Like Jordanians, we saw that among our Syrian participants, m-wallets were of most interest due to anticipation of receiving aid. During Round 2 of our interviews in May 2020, there were already rumors within Syrian participant networks that they might need an m-wallet to receive monthly multi-purpose cash assistance or other aid under COVID-19 response programs.

Ultimately, however, cash assistance was distributed through the regular channels of Iris-enabled ATMs. Thus, while Syrian participants may have gone as far as downloading or even registering for an m-wallet, they did not use it at that time.

None of our non-Syrian refugee participants opened a wallet. Being largely excluded from the humanitarian responses in Jordan, they did not see the need for one. Even those who did need one, such as those who receive regular or one-time cash assistance, were unable to open their wallets because they lacked a valid passport—the minimum KYC requirement for all foreigners. Unlike Syrians, non-Syrian refugees do not qualify for Ministry of Interior IDs, another acceptable KYC for m-wallets.

Pilot programs for m-wallet cash disbursement to refugees

In the push towards utilizing digital payments, including humanitarian transfers, a few organizations have run pilots to disburse cash assistance to refugees through m-wallets. Although small in scale, these have provided some interesting early lessons. For instance:

- A ‘digital experiment’ run by JoPACC and SEP disbursing payments to 262 Palestinian women refugees in the Gaza Camp in Jerash found money transfer to be the key m-wallet use. This digital experiment and a survey run by ILO also highlighted challenges people face in shifting to m-wallets, including difficulty in registration, overcharging by agents, and denial by agents to withdraw small amounts.

- A pilot by GIZ and Zain Cash to distribute payments under the Cash for Work programme has been implemented in Fifa, Azraq, Dibeen, Ajloun, and Yarmouk. About 1,948 workers (vulnerable Jordanians and refugees) benefited from the usage of m-wallets.

- The UNHCR ran a small pilot with Mahfazati where 782 refugees were paid through m-wallets and reported similar challenges on network outreach and fees.

- An assessment by the NGO, Collateral Repair Project (CRP), highlighted how non-Syrian refugees, who comprise more than 80% of CRP’s beneficiaries, are excluded from shifting to mobile wallets as the majority of them do not have a valid passport. That said, none expressed a need for m-wallets in the first place. However, as more humanitarian transfers shift to this channel, NGOs serving these populations will not be able to take advantage of this financial infrastructure.

Making m-wallets relevant for refugee households

Although expected in any nascent mobile money market, operational challenges and network issues as identified in the pilot programs mentioned above affect early perceptions of trust and safety. These challenges are addressed as systems improve and recourse mechanisms are implemented. There are also behavioral barriers that are difficult to overcome. In the context of refugees there are additional barriers as refugees lack secure legal status—making them wary of formal institutions and long-term investments in the country.”

However, as observed in our research sample, the more prevalent reason for the low uptake of m-wallets among refugee households was their perception of m-wallet usefulness or, more to the point, its lack of usefulness.

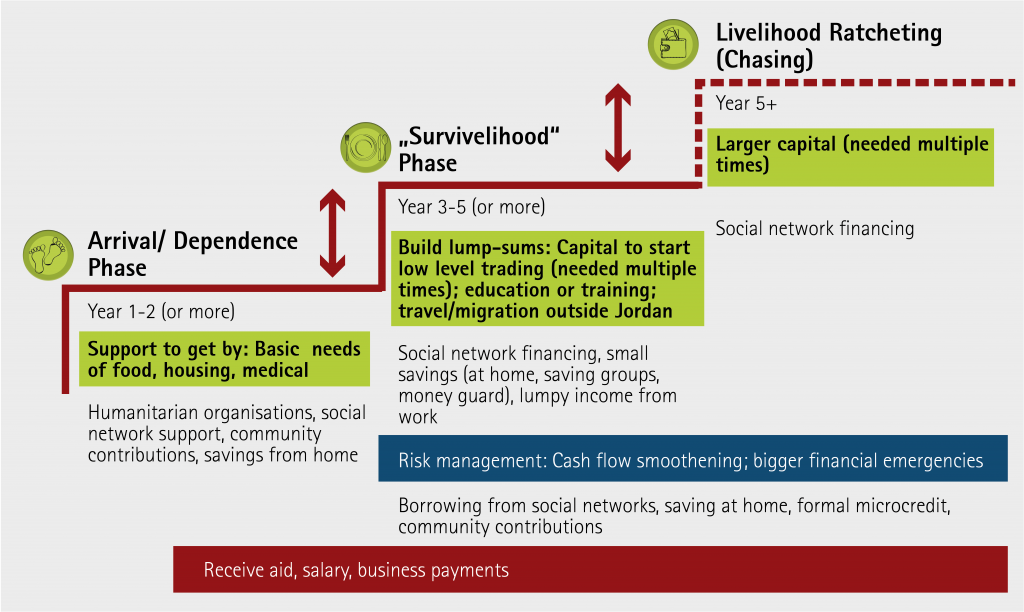

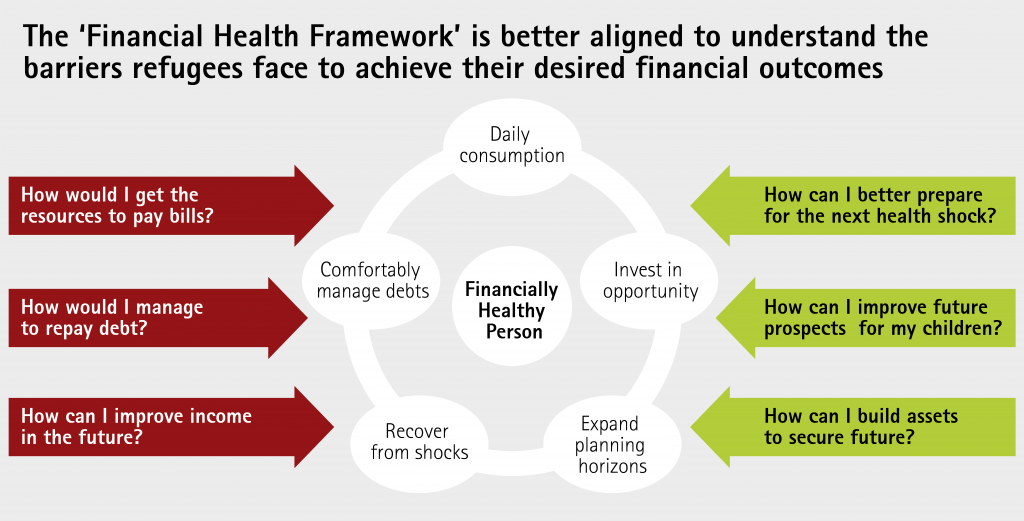

The key reason for the lack of usefulness of m-wallets for refugees is that they did not offer relief from the financial income challenges most refugees faced, except for a Syrian minority who could receive humanitarian assistance more easily than other Syrians and all non-Syrians. For the majority of refugees unable to receive humanitarian assistance, m-wallets’ primary function would be cashless transfers. With unstable incomes and lack of work opportunities, what kept the majority of research participants up at night was not how they could make a payment more conveniently in a cashless way, but rather how they could get the resources they needed to pay bills, repay mounting debts, smooth consumption of food and basic necessities, better prepare for the next health shock, and improve income in the future (see figure 1 below).

Hence, what they faced was not a ‘finance’ problem but rather an ‘income’ problem. Could we then think of how m-wallets could be made relevant to refugees’ ability to generate income and improve resilience?

While payments such as the distribution of humanitarian assistance could be an entry point into the formal financial system, further tools are needed to support real financial inclusion, including those that improve livelihoods, smooth consumption, and strengthen resilience among low-income households.

For instance, the Digiances project at GIZ Jordan has been supporting two pilots with AyaPay and Dinarak for inbound and outbound cross-border remittances that went live in June 2020. This adds a critical digital income source that is potentially much greater than humanitarian payments. We did see a few interesting possibilities emerging from the FIND data where the financial strategies used by participants could be made more efficient if done digitally using m-wallets (see Figure 2 below).

E-commerce and online marketplaces

With the increase in e-commerce, gig economy platforms, and other online marketplaces, m-wallets play an essential role in facilitating payments. Instead of financial service providers pushing for cashless payments, they could encourage uptake with more focus on promoting ecosystems that support livelihoods for refugees and low-income Jordanians.

Mobile money awareness campaigns linked to such use cases might also produce a greater impact than stand-alone financial literacy programs. However, such efforts require collaboration with platforms that support the onboarding of refugee entrepreneurs or gig workers. One such example is the partnership between Mercy Corps and Bilforon, an app-based aggregator for home-cooked meal delivery. Together they are running a pilot to help Syrian refugee women sell home-cooked meals where they can be paid remotely via mobile wallets.

Digital fundraising

Interpersonal domestic remittances are already seen as a relevant use case of m-wallets, especially during the pandemic when mobility has been severely affected. One modified use case for this purpose could be digital fundraising.

Occasionally research participants were crowdfunding money for urgent medical expenses. We saw this among Somali, Yemeni, and Sudanese right after arrival. We even saw this in the later phases among Syrians with relatively wider networks with other Syrians and Jordanians. Another study with Syrian refugees found many examples of kinship finance where Syrian families scattered hither and yon, borrowed from, or lent to help each other out, sometimes in complicated transactions that could be eased with a fintech solution that tackles KYC issues.

An m-wallet could ease these fundraising transactions and even help refugees to reach out to a broader network. Similar platforms implemented in East Africa are also instructive. In Kenya, domestic digital fundraising platforms show that it is more cost-effective for such services to be offered by existing trusted payment platforms rather than third-party providers.

Also, such services appear more successful once network effects have set in, as it might not necessarily encourage more users to sign up. But once the user base widens, m-wallet fundraising tools can be a valuable service for refugees (and low-income Jordanians).

Digital savings

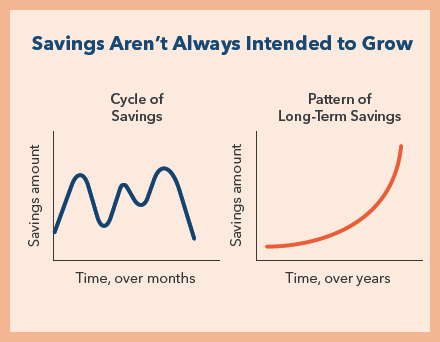

Our participants also expressed their wish to save. Despite the financial hardships they faced, we did see that most kept aside small amounts of money to be used for an emergency or unplanned expenditure at the end of the month. For those with irregular incomes, saving up for rent—a considerable lump-sum required every month—was ubiquitous.

Even though refugees might not refer to these as “savings” and their under-the-mattress balances remain small, we do see a cycle of savings, i.e., putting away money regularly for a specific purpose.

M-wallet providers could design products that support this savings cycle for refugees, low-income Jordanians, and migrants. This means digitizing what cash-based informal savings currently offer, e.g., allowing flexible savings at low or no cost and providing the option of “mental accounting” for users, meaning they can keep separate savings with different purposes. The product design must ensure that these savings remain highly liquid—able to be withdrawn when needed unexpectedly or for a specific goal, as well as replenished as is possible.

One possible product could be a labeled m-wallet with sub-accounts based on a specific savings goal or purpose, to address the inadequacies of mental accounting. Such a product would combine behavioral prompts such as setting a savings goal and then issuing scheduled reminders. Such account should be offered without withdrawal restrictions.

Another example could be to digitize saving groups, allowing for flexible contributions while still making bookkeeping easy and providing a safe place to save through institutional guarantees for pay-outs. One such product is being piloted by a start-up called TANDA in Jordan.

Does mobile money offer hope to financial inclusion for refugees or is it just hype?

There is little doubt that m-wallets with their current use cases are not transformative for refugees in Jordan. They might improve their financial lives only marginally by, for example, delivering humanitarian payments or offering convenient bill payments.

However, as network effects set in and the mobile payments ecosystem matures, financial service providers and the private sector could build up on the digital rails to offer use cases relevant to improving refugees’ livelihoods and financial resilience. In doing so, instead of asking “Why refugees (or host population) could use m-wallets for, say, merchant payments?” we must first ask, “What outcomes do refugees (or host populations) want to achieve and how could m-wallets support that?”.

As we do this, it is important to consider that refugees are not a homogeneous group, but very diverse with a wide range of desired financial outcomes. Apart from different economic segments, it is also crucial to consider the gender differences in the desired outcomes to identify appropriate use cases.

In other words: The key here is to gain a thorough understanding of the financial outcomes that refugees desire, put those at the very center, and identify solutions that help in achieving them most effectively.

SWATI MEHTA DHAWAN

Swati Mehta Dhawan is a Research Associate at the Department of Economic Geography at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt. She is leading the research in Jordan under the Finance in Displacement (FIND) project.

HANS-MARTIN ZADEMACH

Hans-Martin Zademach is Professor of Economic Geography at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt. He currently focuses his research on the fundamental processes shaping social and spatial inequalities and (strong) sustainable devel- opment with a particular focus on financial issues.

We would like to thank our colleagues from GIZ, Joscha Albert and Florian Henrich, for their collaboration and review of this essay.

Fresh FINDings is made possible through a partnership among Tufts University, the Katholische Universität Eichstätt – Ingolstadt (Catholic University or KU), the International Rescue Committee and GIZ. Fresh FINDings also features work sponsored by Catholic Relief Services, Mercy Corps, and the International Organization for Migration.

Contact: Kimberley.Wilson@tufts.edu