Migrant & Refugee Stories: Visual Journeys

Migrant and refugee journeys don’t begin the moment they leave home. Nor do they end once they arrive in a new place. Their journeys are a give and take between making decisions on the fly and intensive planning, when planning is possible.

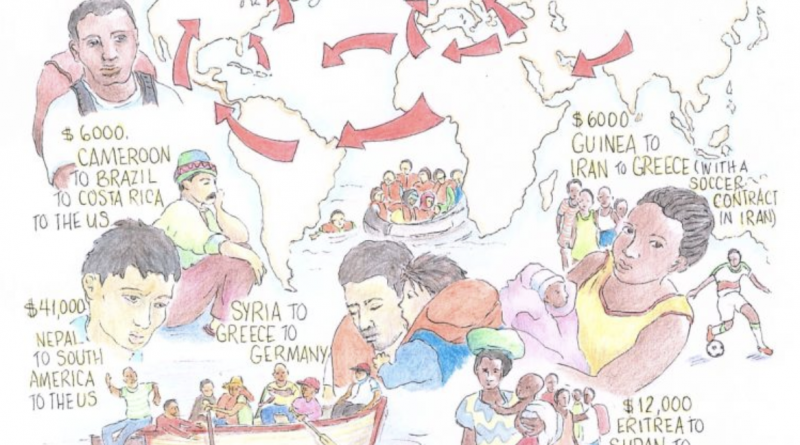

The Journeys Project examines migrant and refugee travels with an emphasis on the financial barriers and strategies migrants use before, during, ad after their journeys.

As we listen to and learn about migrant and refugee stories, we learn of agonizing decisions, of strong and trusting relationships to manage what seems like limitless uncertainty, and a willingness to take on unimaginable risk in search of security.

Illustrations of Migrant and Refugee Journeys

When we hear or read their stories, we may not fully grasp their details or even their essence. The Journeys Project researchers have interviewed hundreds of people who have shared their experiences from what led them to leave their home, how they financed their travels, and what strategies made survival possible. Artwork by our friend and artist, Anne Moses, provides another medium for us to visualize and understand these stories.

**Names and other identifying information in the visual stories and their attached financial biographies below have been changed or omitted for the confidentiality and protection of the migrants and refugees who shared their experiences with us.

Migrant and Refugee Stories

Two Flight Tickets for their Own Dogs and Nothing for Me

After war took her parents, her home was burned down, and her husband lost his job, Stephanie set out to the economic capital of Cote D’Ivoire for work to support her husband and two children. She began with a housekeeping agency, working her way up to employment with the Tunisian ambassador and his family.

Although Stephanie dreamt of going to France or Belgium where she heard there were opportunities to build a livelihood, she wasn’t prepared to risk her life and leave her children crossing the sea. Her cousin contacted her one day, however, and shared hopeful news about life in Tunisia. He put her in contact with potential bosses who told her she would be able to send more money to her family if she came to work for them. Eventually she agreed to take the opportunity.

Despite promises, Stephanie found a challenging situation after her arrival. She was left to clean cars and the large home, cook, garden, and care for the family’s two dogs on her own. The family also informed her they would pay her half of what they’d promised. This too turned out to be untrue. Instead, the family kept full control of her finances, not paying her at all, telling her she could simply ask them if she needed anything and they would take care of it.

After several months, Stephanie received news that her husband and her sister had died, but her bosses would not allow her to leave to make arrangements for the funerals and for her children. For the first two years, Stephanie was able to convince her bosses to transfer money to her children for their school tuition. Taking care of her children, after all, was her motivation for leaving home for work. But, for four years afterwards, the family refused to pay her any salary. Then, the family decided to move to France. They bought plane tickets for themselves and their two dogs but closed their home to Stephanie, and again did not fulfill their long-held promise to pay for her flight home or for any fees she faced (a promise they used to justify withholding the first half of her salary).

Stephanie continued to struggle to find work with reliable pay, or any pay at all. She worked as a caretaker and was able to send money to her family until the old man she cared for accused her of stealing food from the refrigerator and fired her.

She still has hopes of moving to Europe where she can earn a living and provide a better life for herself and her children.

More on Stephanie’s story will be coming soon in Financial Journeys Volume II.

A Shot of Whisky

Rami and Z are Uzbeks who left Afghanistan with four of their five children. After the Taliban threatened to kidnap their sons with the intent of recovering ransom money from the family, Rami and Z decided to leave their business and their three homes in Afghanistan for the safety of their children.

Initially, they tried to apply for a Turkish visa, but the process was expensive, took months to process, and ultimately ended in a rejection. So, like nearly all migrants, Rami and Z connected with a smuggler who would facilitate their journey across the Mediterranean to a refugee camp in Greece.

The family’s journey began by plane, then continued by car, van, ambulance, another car, a ferry, and finally an inflatable boat to Greece. On the boat with about 45 other people, Rami and his youngest son were the only ones who could swim.

Fortunately, the boat remained afloat until it was located by Greek police, and the group was taken to shore. Rami and Z decided to send two of their children to what they hoped would be their family’s final destination—Germany.

Worth the 500-Mile Walk

In Syria, he worked for the United Nations both during and after university. In 2012, however, the agency had to let him go because they were unable to guarantee his safety when traveling through checkpoints in and between war-torn Syrian cities. He was arrested twice for participating in protests and encountered trouble at checkpoints, so he set out for his journey north, wanting to continue his studies away from the insecurities developing at home.

Once he arrived in a “Northern Country,” (he asked us to keep the name confidential) he set out on a 500-mile walk to his destination city. Throughout the journey, he took different jobs to support himself—in a bakery, on a farm, and as a language teacher. At one point he was a bouncer and at another hunted animals for food.

In Turkey, where he now works, he has been able to make a living. Finance and banking limitations, both in Turkey and Syria, have made money transfers home challenging. Still, he has been able to send money home to his family occasionally through transfer networks, although his family prefers he use his money for his own livelihood.

My Sister is My Banker

A family man from Syria is forced to stop working after checkpoints around his hometown restrict travel in and out of town, a necessity for work. Unable to work and witnessing the growing violence in his community, he was forced to leave with his wife and twin toddlers.

To finance the move, he patched together funds from friends and networks to safely travel from Syria to Egypt. His cousin in the Gulf along with his sister and other friends contributed what they could to support their journey. To protect what they had, his wife hid the money in her clothes as they traveled.

Once in Egypt, he picked up multiple jobs at once to provide for his family: translating, teaching online, and working for a tech support company.

A friend sent word of a potential job in Turkey. Because of increasing tensions within Egypt, he knew that once he left Egypt, he would not be able to return. Despite a two-week trial period at the new job, he packed as much of his family’s belongings for his trip and departed for Turkey. He would send for his family once he knew it was secure.

His arrival in Turkey was full of friends, networks, and even strangers supporting the transition. He now works as a translator again, and he is repaying the loans that got him to his destination. His sister manages his debts and payments, and although many who had lent funds were also struggling, some still refuse repayment.

Hercules

Hercules, along with his friend Rose, is an Eritrean who risked his life to flee Eritrea to avoid the country’s military regime and its system of conscription and forced labor, which they described as inhumane. In Eritrea, military service is mandatory and even after their service, Eritreans are mandated to work wherever the government assigns them, which may mean continued — seemingly endless —military or government service. Frustrated and wanting more security than the government allowed, Hercules and Rose had their eyes on leaving Eritrea. “If they catch you trying to cross to Ethiopia,” Rose said, “they shoot you automatically. So everybody goes to Sudan,” and that’s where they wanted to go.

After making the risky decision to disclose their intentions to a Sudanese nomad they thought may be able to connect them to a smuggler, the pair’s journey immediately began. After twenty hours of walking and successfully evading the gunshots and police dogs, the smuggler decided he would not continue to guide Hercules and Rose on their journey.

On their own now, they found a refugee camp with little to no humanitarian services where they shared a home with eighty people and were not permitted to leave freely under domestic law. Hercules stayed there for four months before receiving financial support from friends in Eritrea to pay for a smuggler out of the camp. He found farm work, but soon after starting, he was kidnapped and taken as a slave along with other Eritreans for ransom where he remained for two and half months before being released in Israel.

Hercules worked in Israel on a visa he had to renew regularly until the Israeli government decided it would not keep Eritrean and Sudanese refugees. Hercules went to Rwanda then to Kampala in Uganda hoping to be permitted to work. Ultimately, he hired several smugglers to assist him to get to Sudan where he was routinely arrested by local police despite proper documents and held in detention until he paid the police for his release. His fear of leaving home and being extorted led him to then travel to Turkey where he lives now.

The Beast Tamer

In Honduras, Alexander worked full time and while attending school for seven years until he earned his technical degree in computer science. Still, he could not find technical work to support himself and his family. Employers often paid him less than he earned because they knew he was in need of the money.

He decided to join his then-girlfriend in Mexico, leading to his first trip on “La Bestia.” As is familiar for those riding La Bestia, Alexander and the other migrants on the journey with him were beaten and mugged. Some were exposed to fatal violence against themselves or their families at the hands of criminals.

Still, those on the treacherous journey became close friends, depending on each other for physical, mental, and emotional support. Occasionally, travelers also received support from locals. As the train passed through Mexican cities, some would throw food to those riding La Bestia.

To circumnavigate a particularly notorious stretch of the journey, Alexander and five other migrants decided to take a bus to the next stopping point. After weeks of travel, Alexander and five other migrants were removed from the bus and deported back to their homes.

Alexander decided to face La Bestia again three years later to join his brother in Tijuana. This time he was more experienced and more mature. At the outset, he lost everything except the clothes on his back. That meant no phone to contact his friends with when they were separated and weathering the desert cold at night that he thought would kill him. The trip took him 23 days in total.

In Tijuana, Alexander struggled to find housing at first but eventually found an apartment and was able to find work so he could send money to his mother in Honduras. He has faced challenges with local discrimination and racism. Still, he believes that if someone thinks they will have a chance at a better life and they are prepared for the challenges of the journey, they shouldn’t give up.

More on Alexander’s story will be coming soon in Financial Journeys Volume II.

Find More Migrant and Refugee Stories

These are just a few examples of the experiences shared with us throughout our research. You can find more stories of migrant and refugee journeys in Volume I of our Financial Biographies and our upcoming Volumes II and Volume III.

Also take a look at our Visual Journeys to see more artwork depicting these stories as told by migrants and refugees themselves.

If you’re interested in a deeper dive on the challenges migrants and refugees face and the strategies they use to navigate those challenges, take a look at our Essays and Articles for deeper dives into specific geographic regions or stages of the migration process.