“Modern Art, Ancient Wages”: MoMA Staff Protests and Museums as Employers

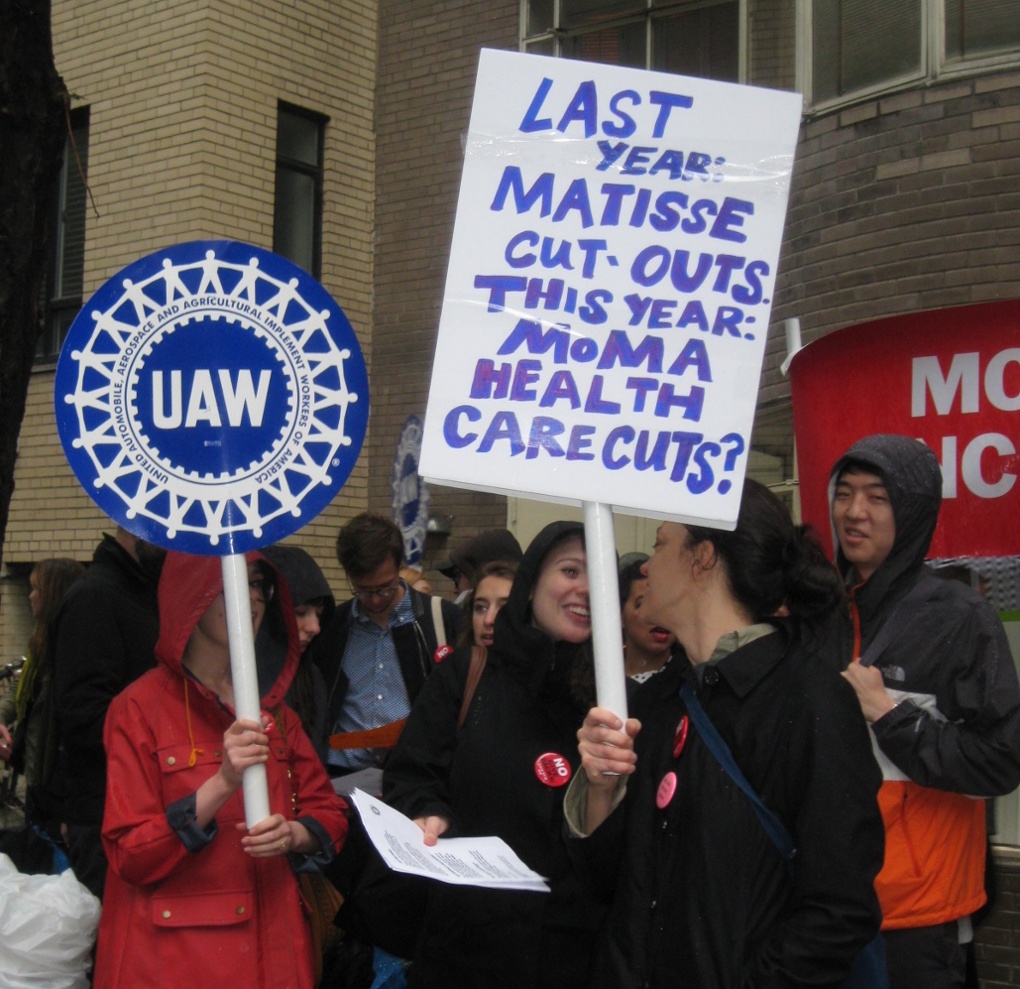

Last Tuesday was MoMA’s annual Party in the Garden, a benefit that honors artists and boasts an impressive VIP guest list. This year, the guests, who paid $25,000 to $100,000 per table, were greeted by dozens of museum staff with signs that read “Modern Art, Ancient Wages” and “MoMA, Don’t Cut Our Healthcare.” The protest, organized by MoMA staff and their union, is in response to proposed cuts to their healthcare plan. While there is a long and rich history of protesting MoMA, these actions highlight the politics of museum employment that extend far beyond MoMA’s midtown territory.

Art history is a strange field. Our scholarship focuses on a world full of very expensive objects with actual monetary values and still manage to produce volumes of fundamentally Marxist-dominated discourse. Art museums are steeped in cultural capital and often have correspondingly high admission fees (obviously, MoMA is no exception to this). However, the salaries of museum employees, the people who are responsible for the museum’s daily function, rarely correlate to the public view of museums as places of wealth.

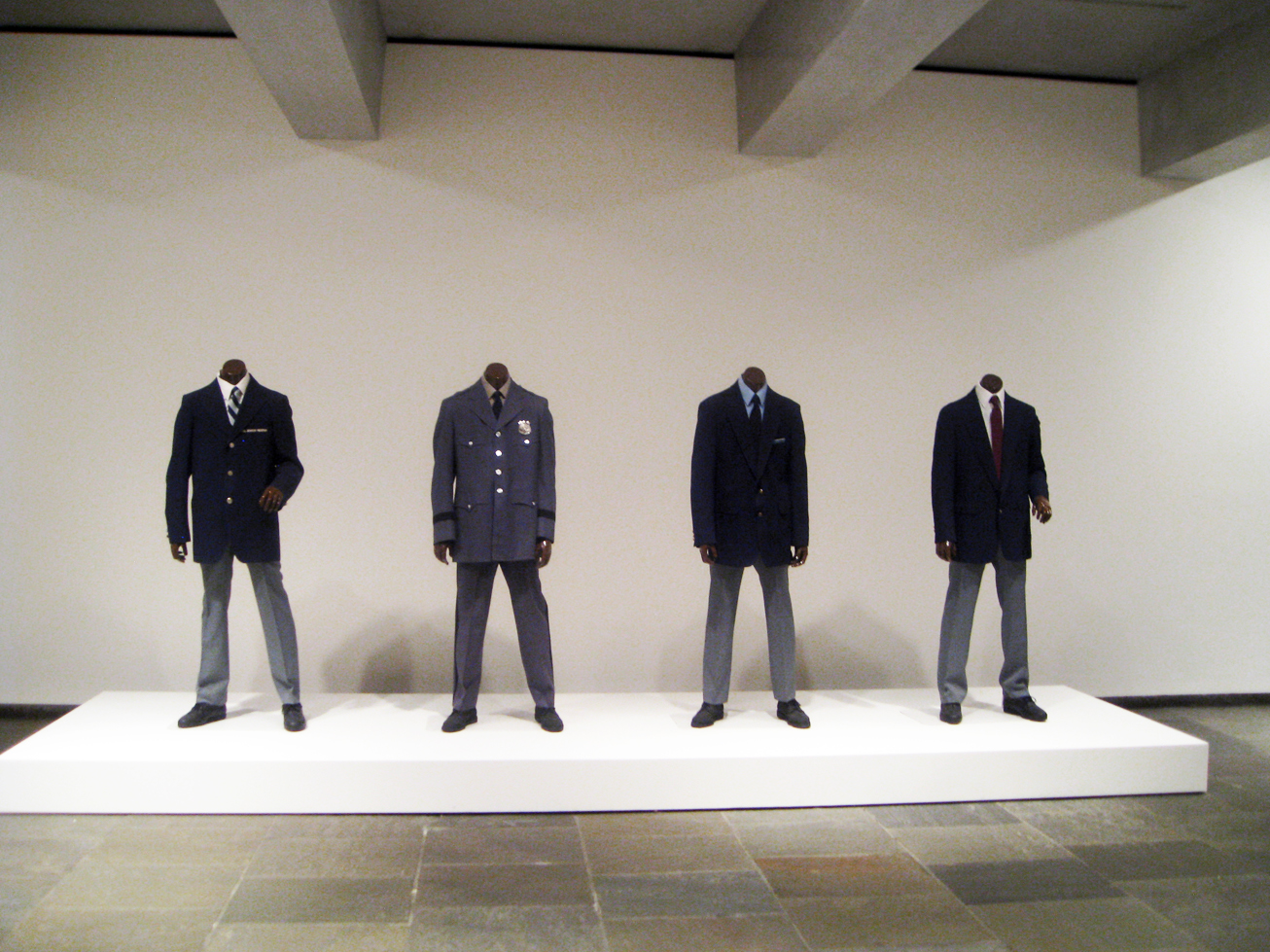

Victoria Wong, a library assistant at MoMA, truthfully told Hyperallergic that “nobody gets a job at a museum to become a millionaire.” Unless you’re working at the very top, the museum world is overly competitive and underpaid (not the mention the gendered and racialized politics of who becomes directors). American artist Fred Wilson perfectly proved the disjuncture between the visibility and respect of different positions in the museum when he dressed in a guard’s uniform and was subsequently ignored by the visitors as part of his 1991 installation, Guarded View.

So why do we choose to enter this field? Personally, I’m doing it because I genuinely care about preserving all material forms of history and displaying them for public access. And although the answer will undoubtedly vary between individuals, I’d bet we all have a honest connection and dedication to the true mission of museums. And if you follow the MoMA Local 2110’s instagram, you’ll get a taste of their undying love for MoMA’s collection, even while protesting. However, no institution should take advantage of its employees’ honest commitment without proper compensation. We talk a lot about making museums inviting and attractive to the public, but we also should hold them to the same standards as workplaces for employees.