Please Touch: The History of Museum Accessibility for Blind Visitors

Though it might seem paradoxical to expect blind and low-vision visitors to enjoy a visit to an art museum—after all, the contents of art museums are often called the visual arts—museums have a long and rich history of proving that this is absolutely not the case, and that they actually have a lot to offer to the low-vision population. And contrary to popular belief, museums’ efforts to make their collections more accessible, educational, and enjoyable to all began long before the passage of formal accessibility legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. As early as 1909, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City created a designated space where blind visitors could touch taxidermied specimens. Six decades later, in the 1970s, there was a proliferation across the globe of art exhibitions curated specifically for blind and low-vision visitors. Most of these exhibitions centered around sculpture, because sculpture is typically more tactile than two-dimensional paintings, drawings, and photographs.

During my final year of undergrad, I chose to research the history of museum accessibility for blind and low-vision visitors for my honors thesis. My research took me to archival collections in New York City, London, Cape Town, Sacramento, Raleigh, and beyond, and the information I found proved fascinating. I learned that art museums have made great strides in the past several decades towards improving their accessibility for all visitors—but at the same time, there’s still a lot of work to do as museums move into the future.

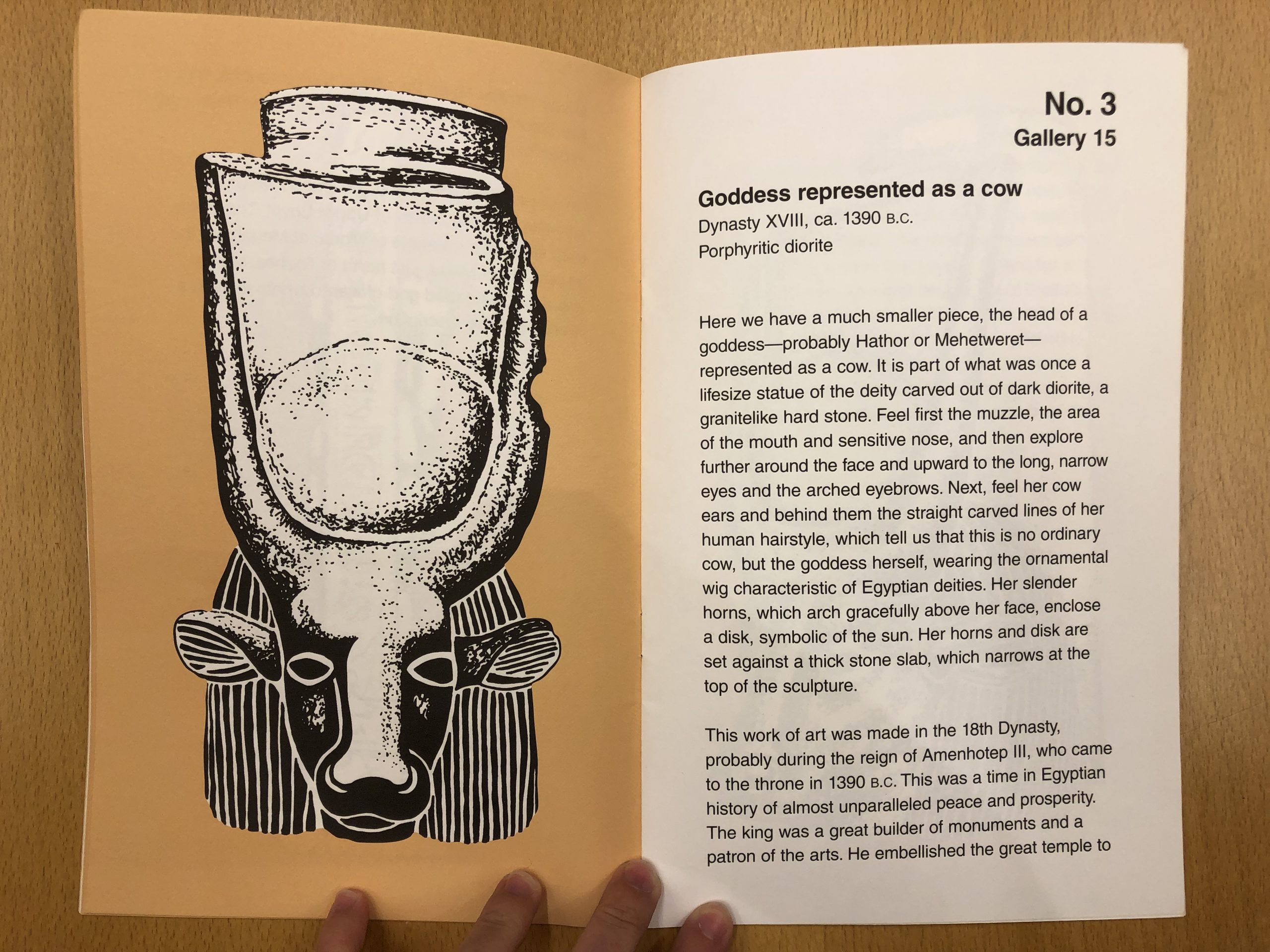

Of the many “exhibitions for the blind” that took place in the 1960s and 1970s, a few stood out to me as the most interesting and best documented: the Mary Duke Biddle Gallery for the Blind at the North Carolina Museum of Art (established in 1962); Dimension (1970) and Perception (1971), two touring exhibitions created by the California Arts Commission; the Touch Gallery at the South African National Gallery (which produced a series of tactile exhibitions throughout the 1970s); the Tate Gallery’s Sculpture for the Blind (two different exhibitions by the same name, in 1976 and 1981); and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s To Touch and Hear (1975), Shape and Form (1977), and In Touch with Ancient Egypt (1996). While each of these exhibitions highlighted different content, all offered visitors the opportunity to touch a range of sculptures in regulated circumstances, often with the help of a museum educator on hand to explain the unique details and contexts of each piece. Based on contemporary reviews of these exhibitions, it’s clear that they were extremely popular with visitors both blind and sighted: a blind student named Michael Esserman, who visited the Met’s Shape and Form and had the opportunity to encounter works ranging in time and place from the Ancient Near East to the twentieth-century United States, wrote in a letter to the museum that visiting the exhibition was “a most interesting and rewarding experience.”

In my research, I also looked at more recent—that is, post-ADA—efforts by art museums to welcome blind and low-vision visitors in an equitable, authentic way. I’ve found that while museums consistently offer ramps, handrails, and Braille and audio versions of their content, the spirit of creativity that reigned fifty years ago and led to the tactile exhibitions mentioned above seems to have waned. Is it possible that museums’ focus on binding accessibility legislation has caused them to prioritize offering more tokenistic accessibility measures that do little more than meet legal obligations? This is up for debate, but in any case, museums can always do more to make their collections more accessible to people of varied abilities. Physical accessibility measures like ramps and elevators are not enough in themselves—museum educators need to take more creative approaches as well to make sure that art collections are intellectually accessible as well. Maybe by recognizing the rich precedent of museum accessibility, especially the efforts that were made before accessibility legislation was passed, art museums can reignite their commitment to genuine accessibility measures and challenge misconceptions about who is welcome within their walls.