Combating the Hydra of Prison Corruption in Greece

Combating the Hydra of Prison Corruption in Greece

By: Aristeidis Bouras and Ioannis-Angelos Laganis

A Monday Morning Reminder: The Persistence of Prison Corruption

February 12th, 2024 started like any other Monday morning—until a Greek judge received an unexpected package in the mail, sent under the name of the National Association of Judges and Prosecutors. The package housed a poorly made bomb. Its grotesque delivery was orchestrated from within prison walls using smuggled phones and illicit networks operating behind bars. This brazen incident was not an isolated case but a stark reminder of Greece’s deep-rooted struggle with prison corruption.

In the heart of Southeast Europe, Greece still grapples with a nagging shadow undermining the foundations of criminal justice and the state’s rule of law. Prison corruption is a multifaceted beast born from the depths of systemic failures—thriving in the dark corners of underfunded facilities and overcrowded cells and feeding on the vulnerabilities of a system strained far beyond its limits. The symptoms of this deep-rooted issue are manifold: spanning from bribery for basic amenities, to contraband smuggling rings, and a pervasive culture of impunity among prison staff. The message to stakeholders should thus be clear and concise:

“Alleviating prison corruption is not a luxury; it is a necessity and a priority for any self-respecting democracy.”

The challenge at hand becomes not merely addressing these symptoms but also confronting the hydra-like beast head-on, acknowledging that recklessly cutting off one head will undoubtedly sprout two more. Corruption itself is both inherently adaptive and resilient, and as such, a complex and nuanced mitigation strategy that shifts away from reactive measures towards a proactive framework for systemic reform is required.

An Organizational Psychology Approach

Drawing from proven concepts of change theories, such as renowned psychologist Kurt Lewin’s “unfreeze-change-refreeze” model, it is evident that successful organizational transformation requires a structured approach. Change theories emphasize the importance of understanding resistance to change, addressing psychological and structural barriers, and fostering an environment conducive to long-term improvement.

To initiate the unfreeze step, we should first create the sense of urgency for change by highlighting the risks of failing to adhere to international standards. Next, the change phase necessitates reforms be implemented across all three levels of Schein’s organizational culture theory, i.e., artifacts (visible structures and processes), espoused values (formal strategies, goals, and philosophies), and underlying assumptions (deeply ingrained beliefs and norms). Finally, to carry out the refreeze step of this model, one must integrate supervision and feedback mechanisms that reinforce new practices, ensuring they become embedded in the organization’s culture. A lack of sustained reinforcement is a classic failure point of anti-corruption initiatives.

Unfreezing the “Beast”

The United Nations’ Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules) and the UN’s Common Position on Incarceration are central in the “unfreeze” phase. The role of actors such as civil society organizations and non-profits, proactively advocating for the implementation of these frameworks, could act as the “need to change” component of the equation.

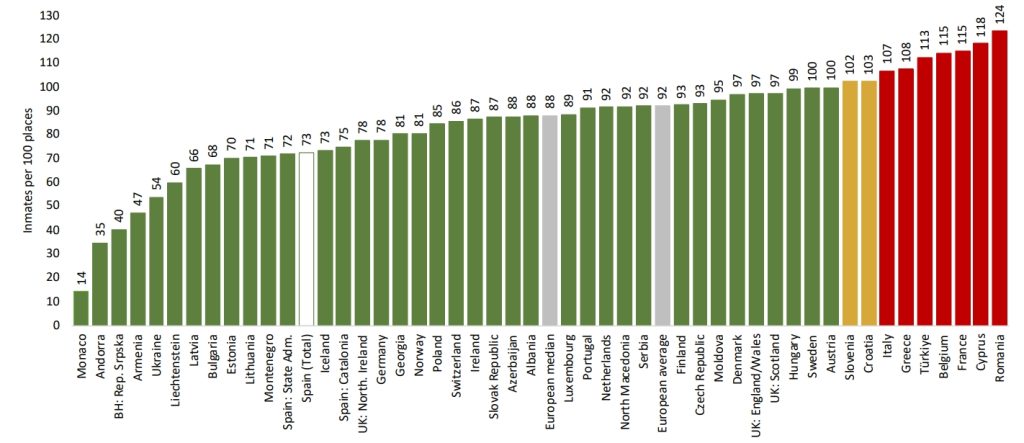

To align with international standards on humane living conditions, Greece must primarily address the growing concerns of overpopulation in its prison system, as illustrated in Figure 1. A recent State Department report on human rights practices illuminates the current state of Greek correctional facilities by noting that “prison and detention centers remained overcrowded, often with inadequate sanitation or health care.”

Figure 1: Prison density (number of inmates per 100 detention places) on 31 January 2022

A critical step in addressing this issue is investing in prison infrastructure improvements. This approach is also supported by the “Broken Windows Theory,” which posits that, visible signs of disorder and neglect—such as vandalism and lack of cleanliness in prisons—can unintentionally foster increased delinquent or antisocial behavior among inmates, leading to an overall decline in institutional control. Therefore, it is clear that upgrading facilities to meet humane living conditions is not only a necessary step towards compliance with international standards but also a multi-faceted solution to improving prison environments and reducing negative behaviors.

Engaging & Changing

The cultivation of an integrity culture within the prison workforce undoubtedly stands as the pillar for our anti-corruption strategy in its change phase. This involves not only rigorous vetting and training of new staff, but also the implementation of continuous professional development programs that reinforce ethical standards and provide clear guidelines for conduct. Additionally, implementing enhanced security measures, including state-of-the-art surveillance technology, can help during this phase as such measures are likely to curb the smuggling of contraband, a major source of corruption as seen in the most recent case of the Avlona Prison in Attica, Greece. However, security technology alone is not a panacea nor its absence thereof an excuse. To be effective, it must be complemented by rigorous training on-site and ethical grounding of prison staff, thus instilling to prison staff a heightened sense of duty, integrity, and professionalism.

In conjunction with staff training, it is essential to reform inmates’ education and rehabilitation programs. By focusing on rehabilitation in particular, we can combat the recidivistic “revolving door” prison culture and transform it into one of hope and opportunity.

The “Tufts University Prison Initiative at Tisch College” (TUPIT) serves as a prime example of such an educational program as it provides opportunities for incarcerated individuals to pursue educational opportunities. Greece seems to be engaged in such initiatives on both a national and regional level, as indicated by its participation in the EU’s Convicts Upskilling Pathways Project.

Solidifying the much-needed reform

Moving past the core points of the aspiring reform, and to carry out the refreeze step of this model, one ought to guard against any threats to the sustainability of the initiative. At this point, the crucial role of transparency in the fight against corruption cannot be overstated. By fostering an environment where actions and decisions are openly made, the opportunities for corrupt practices to take root are significantly diminished. This can be achieved through several means, including: the publication of regular reports on prison conditions (which as of writing are scarce to non-existent in the case of Greece), the establishment of clear channels for reporting misconduct, and the effective protection of both staff and inmate whistleblowers.

With respect to the latter, encouraging inmates and staff to report corrupt activities without fear of retribution should be the priority of any administration and is a vital step toward transparency.

“Send him this message…I am Claudian Lekocaj, and I will slice his head like a chicken“[1],

reads an excerpt from a phone call transcript between a convicted felon from inside prison and the secretary of former Minister of Finance and attorney-at-law Dimitrios Tsovolas. In this hostile and coercive environment, one can fathom the importance of protecting whistleblowers. Enacting legislative reforms, such as the launch of a revised penal code by the Greek Ministry of Justice, adds an extra layer of security to those who expose corruption, albeit is not sufficient nor effective enough, as, in reality, the instigation of a whistleblowing process is often hindered by significant bureaucratic obstacles (coming to no surprise to those more familiar with the Greek public sector).

Towards a less corrupt & more humane prison

Lastly, and while this piece argues in favor of a proactive rather than a reactive/punitive approach, it would constitute wishful thinking to state that the former alone suffice to curb corrupt practices. Corruption is a hydra-like beast that will rebound through simple reliance on “watchdogs” without the establishment of effective “guard dogs” mechanisms. Watchdogs, while crucial for monitoring and reporting, often lack enforcement and implementation power, leaving room for malpractices to continue unchecked without more robust, action-oriented guard dogs that prevent and penalize corruption. Empowering existing government agencies will ensure the meaningful implementation of the enacted anti-corruption policies.

Conquering a Herculean feat: Defeating the “Hydra”

As we stand at the crossroads, the path forward is clear. Much like its mythical counterpart, the modern hydra of prison corruption in Greece requires a concerted effort that embraces a holistic view of the problem. Only then can the foundation for a just and rehabilitative prison system be laid. In pursuit of this goal, policy-makers should seek to drastically change the existing paradigm with the support of all the stakeholders involved. The focus of this endeavor should not be solely the enforcement of stringent oversight and accountability measures as per the latest penal code revisions. We must reinstate a new vision for our prison system as a truly rehabilitative state institution. It is not just the integrity of our prisons at stake, but the very essence of our democracy at its birthplace, Greece.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect, nor should they be interpreted as reflecting, the official positions or policies of the organizations with which they are professionally affiliated.

[1] Authors’ Note: Verbatim translation from Greece

Featured image above from “Investigation Points to Corruption in Jail” by Yiannis Souliotis, published in Kathimerini (electronic version).

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Aristeidis Bouras

Aristeidis Bouras is a law enforcement professional with 20 years of experience directing operations related to organized crime and anti-corruption cases, holding leading positions primarily in the Homicide and Kidnapping Unit of Athens, the Anti-Extortion Unit of Thessaloniki, and the National Anti-Corruption Agency of Greece, where he served as Deputy Commander and Section Leader.

From 2017 to 2024, he served as an active member of the Greek Crisis and Hostage Negotiation Team, managing critical incidents such as hostage situations in prisons and suicide interventions.

From 2019 to 2023, Aristeidis lectured at the MPSOTC, a training center of the Hellenic Armed Forces that provides certified training under the auspices of the UN, NATO, the EU, and the OSCE. His lectures focused on anti-corruption strategies and building integrity, training international participants from military, law enforcement, and civil society backgrounds.

In June 2024, he joined Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, as a Senior Standing Corps Officer, supporting the Agency’s operational activities within its respective mandate, which includes assisting EU Member States and Schengen Associated Countries in managing the EU’s external borders, combating cross-border crime and terrorism, and ensuring the respect of fundamental rights.

He holds a Master of Arts (MA) in International Relations & Global Affairs from The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, as well as Bachelor’s Degrees in Psychology, Economic & Regional Development, and Homeland Security & Law Enforcement, underscoring his multidisciplinary approach to public service and security.

Ioannis-Angelos Laganis

Ioannis-Angelos Laganis is an Army officer currently serving as a Staff Officer at the Hellenic Army.

Previously, he served as a Military Instructor and International Cooperation Officer at the Hellenic Army Academy, as well as, a Company Commander on the Greek-Turkish borders, where he honed his leadership and operational skills.

Ioannis-Angelos holds multiple advanced degrees, including an MA in International Relations from The Fletcher School (Tufts University), cross registering with Harvard University and an MA in Social-Organizational Psychology from Columbia University, both earned through prestigious full scholarships. He also published pieces on leadership development and mentorship through the lens of a military professional.

Fluent in Greek and English, with limited proficiency in German and Japanese, he brings expertise in organizational development, change management, combined with an extensive toolkit on Military Diplomacy and International Affairs.