Somali Refugees in Maine: Social Capital in Non-Urban Communities

Lewiston, Maine is like many of the old mill towns of New England. Abandoned mills sit at the center of the city, memorials to the city’s heyday before the textile industry relocated overseas. Beginning in 1956 with the closure of the Androscoggin Mill, a series of textile closures hit Lewiston, devastating the city’s economy. The last half of the 20th century was defined by decades of continuous population loss and decreasing wages. Between 1970 and 2000, the city’s population decreased by 15%, and Lewiston’s family and per capita income fell to the lowest ranking in Maine. By 2000, Lewiston’s downtown area became the single poorest census tract within Maine, with a poverty rate of 46%.

While “rural flight” and economic decline are not unique to this Maine city, Lewiston found a way to rebound starting in 2001, with the arrival of more than 1,000 Somali refugees who had previously been resettled in various locations across the U.S. With the refugees’ arrival, Lewiston became one of the fastest-growing communities in Maine.

Refugees in Lewiston, Maine

Depopulation and economic decline are not unique to Lewiston; they are commonplace in non-urban and rural communities across the world. For the first time in more than 30 years, many states in the United States recorded declining populations; most of these are majority-rural states such as Wyoming, West Virginia, and North Dakota. Half of the rural communities across the country now face such high levels of depopulation as young people leave for urban areas that deaths outnumber births. Approximately 22% of people living in the rural regions of France, Spain, Greece, and Portugal are “elderly retired,” and only 10% of farmers in the European Union are below the age of 35. This phenomenon of non-urban communities losing population to more urbanized areas has been dubbed “rural flight.”

But unlike other communities confronted with decline, Lewiston found a way to rebound starting in 2001, with the arrival of more than 1,000 Somali refugees who had previously been resettled in various locations across the U.S. With the refugees’ arrival, Lewiston became one of the

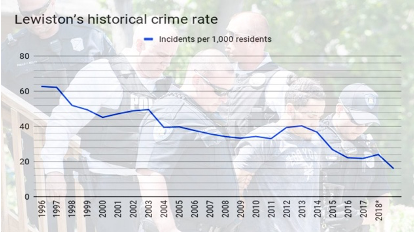

fastest-growing communities in Maine. The crime rate declined, rent prices stabilized, and the city’s economy and population have continued to grow ever since. To quote Professor Catherine Besteman of the nearby Colby College, “Lisbon Street [the main street in Lewiston] had a lot of empty storefronts, and now it’s full of Somali cafes, translation agencies, [and] a mosque.”

While it is an almost unbelievable feat to resurrect a dwindling community, this phenomenon of refugees finding success and revitalizing a small declining community is not unique to Lewiston. Examples can be found across the world in places such as Loubeyrat, France; Lower Saxony, Germany; and Nhil, Australia[1] as well as in other American communities such as Central Falls, Rhode Island; Rutland, Vermont; and Clarkston, Georgia (all small towns whose mayors requested that the federal government resettle more refugees in their communities).

Refugees play a crucial role in several rural economies in the United States at a state level too. North Dakota, for instance, would have suffered a significant population loss between 1990 and 2000 if not for an influx of Bosnian refugees who moved to the state. This population bump led to Republican Governor John Hoeven’s assertion that North Dakota had a “strategic interest” in maintaining a robust refugee resettlement program to help stabilize and grow the state’s population.

Which leaves us with the question, “Why?” Why are refugees able to find financial success in small and declining communities while native-born Americans are leaving? Why would refugee communities who already face challenges in finding jobs, homes, and resources choose to leave urban areas with formal support systems in favor of rural communities where no such support systems exist?

The answer may lie in the difference in the value of social capital between resettled refugees and native-born Americans and the availability of that social capital in rural and urban areas. Friendships, informal networks, and cultural connections may play a more central role in success for refugee communities than native-born Americans. These relationships are likewise thought to be more valuable to well-being and success for small communities than for urban ones.

What follows is an analysis of the role of social capital in the success of refugees in small and declining communities. We will be looking at the role that friendships and informal networks play in influencing refugee groups to migrate to rural communities, the effect that refugee populations have on the social capital of a non-urban community, and whether friendships and informal networks are uniquely valuable in creating successful resettlement and integration.

Theoretical Framework

No two communities are the same, and the causes of community decline are similarly varied. Inhabitants might abandon rural areas because of natural disasters, the promise of better pay in nearby urban areas, or a lack of opportunities in higher education. This variance makes it challenging to create a theory that would explain the growth or decline of every non-urban community, but we can discuss the general patterns of declining communities.

Many believe that the small communities that survive “rural flight” are able to do so because of the community’s high level of social capital. Sociologists such as Pierre Bourdieu define social capital as the advantages that one gains due to their membership and relationships in a particular group. Experts in rural development, like Georg Wiesinger and Jeremy Rifkin, have in turn theorized that social capital is more valuable in non-urban communities than in urban settings and that small communities with high levels of social capital can avoid rural flight and rural marginalization. Essentially, the culture, mutual trust, and friendships in a non-urban community create sufficient incentive for its population to stay.

This theory could explain communities like Lewiston that grow while other communities facing similar pressures—such as deindustrialization and population loss—decline. Refugees bring new and unique cultural and personal connections to non-urban communities that incentivize them to stay while native-born Americans leave. Researchers on refugees in rural communities such as Stacey Haugen have also argued that small towns are uniquely positioned to utilize their strong bonds and social capital to create welcoming environments for new refugee arrivals, an impossibility in urban resettlement destinations. Additionally, migration experts such as Kimberly Huisman have argued that the role of social capital in the secondary migrations of refugees has largely been understated and that it could play a significant role in the decision-making process of refugees choosing to move to small communities.

Key Vocabulary and Concepts

The phrase “rural flight” refers to the phenomenon of populations leaving small communities for more urbanized ones, often described as the flip side of urbanization. This definition is broad and covers everything from agricultural communities with only a few hundred residents to small industrial cities with thousands of residents.

Generally speaking, however, rural flight refers to population decline in areas whose population is below the U.S. Census designation of an urban area (50,000 people). In this paper, communities suffering from population loss and economic downturn will be referenced as “declining communities” regardless of the causes of their decline. Refugees who move from an urban area to a rural area perform a “secondary migration,” which refers to a refugee moving from the community that they were initially resettled in, to another.

The broad theory of social capital encompasses two sub-categories of capital: “bonding” capital (social capital within their refugee communities) and “bridging” capital (social capital that extends outside their refugee communities to host populations). Bonding capital is social capital that strengthens the connections between in-group members (in the current context, between members of refugee communities). Bridging capital is social capital that bridges ties between in-group and out-group members (in the context of this paper, between refugees and their host communities).[2]

Secondary Migrations in the U.S. – Moving to a Small Community

Refugees rarely settle in non-urban communities upon arrival in the United States; the vast majority of refugee resettlement occurs in major metropolitan areas. As of 2017, the United States resettled 98% of all refugee arrivals in large metropolitan areas. And the process of performing a secondary migration, let alone to a small community with few resources, is arduous.

The 1980 Refugee Act dictates that the Director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) “take into account the secondary migration of refugees to and from the area that is likely to occur” while determining resettlement destinations and deciding ORR programming. Yet, many argue that secondary migration has not been prioritized in ORR policymaking decisions, nor has the ORR recorded reliable data about secondary migrations of refugees in the U.S.

Migration scholars such as Eleanor Ott argue that the ORR has a “sedentary” bias—that ORR policy is designed with the understanding that refugees will not move from their original resettlement destination and that there are thus few structures in place to support refugees who move from their initial resettlement destination. Smaller communities that have become prominent secondary migration destinations, such as Fort Wayne, Indiana, have written open letters stating that they lack sufficient resources from the federal government to support their growing refugee communities because of the ORR’s inability to collect data on secondary migration and create responsive policy.

All of this to say, it is a challenging process for a refugee to relocate from their original resettlement destination within the U.S. to any secondary destination, let alone to small community that lacks traditional support networks found in major metropolitan areas. Refugees who migrate to a second destination forfeit access to traditional forms of support and capital.

Due to its “sedentary bias,” ORR policy surrounding secondary migration forces refugees moving to non-urban communities to rely on social capital rather than traditional economic capital that tends to be more readily available in urban areas, such as benefits from a VOLAG. Conscious of this trade-off, the decision for refugees to move to non-urban areas nonetheless, their desire to move to a second destination despite known limits in access to traditional resources, points to a higher value refugees place on social capital than native-born Americans.

Let’s examine the primary reasons refugees move to non-urban communities and how their decisions and experiences are defined by social capital. As a case study, we will draw primarily from Somali refugees in Lewiston, Maine, which provides ample information relative to similar declining communities.

Housing And Education

When Somali migration to Lewiston began, it baffled migration experts and city officials alike. To quote Lewiston city official Phil Nadeau, “What confounded most refugee resettlement experts about Lewiston’s secondary migration relocation activity was the absence of any activity or industry that might have influenced their location decisions to the city.” Rather than moving due to economic motivations such as higher wages, Somali refugees moved to Lewiston to improve their quality of life and establish a community.

Housing is the most cited reason by academics for refugees to leave their original host communities in favor of non-urban secondary destinations. And there is a good amount of evidence to support the claim that housing is the principal reason refugees decide to move to a small community, where housing is much more available and affordable in than in large urban cities.

In Maine, in the year 2000, there was only a 3% housing vacancy in Portland versus a 20% housing vacancy in Lewiston. Refugees who felt that they could not compete in the housing market in Portland would have found it much easier to find a home or an apartment in Lewiston. This could have easily been an incentive for the first wave of Somali refugees to move from Portland to Lewiston. Additionally, rent in Lewiston was comparatively low relative to Portland. The average rent for an apartment in Portland was $598 per month compared to an average rent of $408 per month in Lewiston. And housing is not a unique priority to refugees who moved to Lewiston. For instance, cost difference and housing opportunities are cited as the primary reasons Somali refugees left their original host communities in St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, for the small town of Faribault, Minnesota.

Tied to the desire for better housing is that there are often better educational opportunities in non-urban communities than metropolitan resettlement destinations. One key reason Somali refugees decided to move to Lewiston was they believed their children would receive a better education in Lewiston public schools and the public university system in Maine than in their original host communities. To quote a Somali resident of Lewiston who had just graduated high school, “In contrast [to Boston] we definitely have gotten our education. I just graduated and we have been a lot safer here and the schools have been more structured, more serious, and more willing to help us.”

It should be noted that this prioritization on housing has benefits for the host community as well. When Lewiston still had a decreasing population and a housing vacancy issue—where the number of housing units far outnumbered the people able to fulfill them—residents practiced “apartment hopping.” In other words, to avoid paying rent, tenants would stay at a unit until they received an eviction notice and then “hop” to another apartment in Lewiston and repeat this process. With the influx of population of Somali refugees, the number of vacant housing units plummeted, preventing tenants from apartment hopping, ultimately stabilizing the rental market as a whole in the city of Lewiston. The stability refugees’ resettlement brought to the housing market is, in itself, a form of bridging capital between native-born citizens of Lewiston and new refugee arrivals.

Another example of bridging capital in this example exists in the refugees’ participation in education systems. To quote the principal of an elementary school in the downtown Lewiston area, the area around his school was defined by “groups involved with drugs [and] having fights.” School teachers and other Lewiston residents hope the influx of Somali refugees into downtown Lewiston will help the downtown area recover from its post-industrial crash—that more people will mean more families, more students, and better schools and, eventually, a better downtown district.

Housing and education, the foremost priorities for refugees moving to non-urban spaces, speaks volumes about refugees’ relationship to social capital relative to native-born Americans. When refugees view these as a priority, they commit to making themselves a part of the community for the long term. The same affordable housing opportunities in non-urban communities are equally available to native-born Americans, yet, massive out-migrations of native-born Americans suggest economic opportunities in urban areas are prioritized over homeownership, while refugees place higher value on the social elements that come with owning a home and childrearing.

Employment

Unlike native-born Americans who believe better jobs are in larger cities, refugees often view the opposite. One Somali refugee in Lewiston compared his decision to move to Lewiston to the nomadic tradition in Somalia of searching for “greener pastures.” This is ironic considering native-born Americans’ perception of opportunity, commonly motivated to leave rural areas to find better employment opportunities in urban spaces. Massive out-migration of native-born Americans leads to significant labor shortages in key industries in rural communities, such as manufacturing and food processing, opportunities that refugees take advantage of.

In Lewiston, many refugees are employees at the L.L. Bean factory, which has made significant efforts to create bridging capital by accommodating cultural differences between native-born and Somali employees. This includes adapting work schedules for prayer and religious holidays, adjusting company policy to accommodate religious and cultural attire, and training employees in English. L.L. Bean also mandates native-born employees take a course on Somali culture to encourage cross-cultural understanding and communication. One L.L. Bean manager explained the practical reasons for an employer to invest in bridging capital between Somalis and the host community. “We’re trying to create that [welcoming] environment because we need employees. If we don’t have a welcoming environment, we won’t get employees.”

Refugees’ participation in the job market in rural communities acts as a form of bridging capital between themselves and their host communities beyond the workplace as well. Labor shortages pose existential threats to small communities, and refugees can often be seen as life-saving additions.

Take the town of Nhill in Victoria, Australia. Nhill has a population of just a few thousand, and their primary industry is manufacturing Luv-A-Duck rubber duck products. Fearing the plant would close due to a labor shortage, the town began a refugee resettlement program in 2009 that resettled Karen refugees from Myanmar. In 2015, Deloitte reported that the resettlement program generated $41.5 million for the Nhill economy. Beyond the economic benefit, there has also been a dramatic change in the social capital of the town. Economist David Smerdon found that relative to other rural communities in Victoria, Nhill had a dramatically higher opinion of refugees. Not only that, but as a whole, Nhill had much richer social capital than other towns in the region; compared to other towns, residents were more likely to volunteer, had more trust in their community, and felt safer.[3]

Most literature regarding immigrants who decide to move to a new community for economic opportunity describes them as competing for resources with the native-born community. Yet data from Nhill and similar communities like Lewiston shows that refugees’ participation in the labor market in non-urban communities is a benefit rather than a detractor to the resource supply both in the workplace, the broader economy, and available social capital as discussed above.

Discontent With Original Host Community

As stated earlier, 98% of refugee resettlement in the United States takes place in metropolitan areas. Refugees see many urban neighborhoods as untenable. One of the unfortunate realities of refugee resettlement in the United States is that refugees are often resettled into poverty. In Kimberly Huisman’s piece Why Maine?: Secondary Migration Decisions of Somali Refugees, she analyzes the decision-making processes of Somali migrants who migrated to Maine. She says many of the Somali refugees surveyed were “initially resettled in large, inner-city neighborhoods characterized by high crime, drugs, gang activity, substandard housing, and grossly underfunded schools.”

To quote a Somali refugee who moved to Lewiston from his original resettlement destination of Atlanta, “Many…refugees are [re]settled in are very deprived communities. So, by the time you come and realize where you are, it’s like, “Oh my God. Where am I living in the U.S.? Is this the country I was coming to?… It’s these very tough neighborhoods where even the front doors have gates, and the whole night what you hear are police sirens and gunshots and murders.”

Many refugees did not feel safe or welcome in their original host communities within the United States. They felt their presence was only adding “tension” to an already threatening environment. Huisman writes that a key reason families in particular decided to move to Lewiston was that it had a reputation as a safe city. In many of their original host communities, Somali refugee children were often bullied or even attacked due to their heritage.

But this is different in small communities; parents trust their children will be safe. Many Somali youths in Lewiston have reported that living in Lewiston has enabled their parents to keep better tabs on them than in their original resettlement destinations. One says of the experience, “We joke all the time when we see someone and say, ‘How much do you want to bet that my mom’s gonna call me knowing where I am right now?’ It’s kind of a joke. They can keep a closer eye on us because it’s a small town and everybody knows each other.” The culture and sense of mutual trust in these communities is of immense value to refugees, weighing more heavily in their decision to move than other factors such as potentially higher wages associated with urban communities.

Altona, Manitoba, and Community-Based Resettlement Systems

We have seen how social capital influences the decision for refugees to leave their original resettlement destination in the United States, and how it shapes how they interact with their new host communities. But Canada has taken it a step further and developed refugee resettlement programs specifically based on the use of social capital.

Out of all refugee-receiving nations in the developed world, Canada has devoted the most effort to supporting rural resettlement programs. Many small communities have started their own resettlement projects through the country’s “private resettlement” program in which communities can volunteer to become refugee resettlement destinations. Canada has even started a pilot program to send refugees to rural areas to bolster the population and economy. The success of these refugees in rural and declining communities could have broader implications for resettlement policies more generally, which currently promote initial resettlement in large metropolitan areas.

Let’s look at how this model is practiced in the community of Altona, a small, largely Mennonite village in Manitoba with a population of around 4,500. Altona is growing in population, a rarity amongst other rural communities in Manitoba. There is massive migration of people from rural Manitoba to major cities, causing significant labor shortages across the province’s rural communities. Some estimates show that for every 100 people leaving the labor market in rural Manitoba, there are only 50 entering the market.

While most other rural communities in Manitoba are struggling to maintain their populations, Altona has prevented population decline from rural flight by resettling refugees there. Through resettlement, Altona has taken in one of the largest (if not the largest) per-capita refugee populations in the United States or Canada. As of 2019, they had taken in 30 refugee families, in some instances increasing the town’s population by whole percentage points.

Altona has a unique resettlement model based on using the social capital of the small town to promote the integration and success of its refugees. Before a refugee arrives, the town assembles a team of ten to thirty community members to help the refugee integrate and learn about life in Altona. This includes meeting them at the airport when they arrive, opening bank accounts, helping them navigate the healthcare system, and even teaching them how to curl. Before each family arrives, the community (through the resettlement organization “Build a Village,” which started as a community project to build homes for the underserved, then grew into a resettlement program) makes sure that they have found and furnished a home in Altona for the family.

And the system seems to be working well. To quote Doha, a young Syrian refugee in Altona who has become the town’s unofficial ambassador, “We’re like one family…. When you need help, you can ask your neighbor.” Doha believes that she wouldn’t be able to find that kind of environment in a larger city. Altona, and small communities like it, are places where everybody knows everybody, and the refugees who resettle there have the social capital that comes with that environment.

One reason for Altona’s welcoming nature is its history. Several of the town’s ancestors were Mennonites who fled persecution in Russia between the 1870s and 1920s. Many current residents see their resettlement program as a way to honor that history and help others in the same way their ancestors were helped. The mayor of Altona, Melvin Klassen explained, “They’re saying, ‘It’s payback time…. We need to do that for others right now.’”

Although the resettlement program has undoubtedly been beneficial to the town’s economy, Roy Loewen—who started Build A Village and has led the resettlement program since its start—has made it very clear that that is not their motivation. While the economic boost is a nice benefit, the town’s involvement is for humanitarian reasons.

When Social Capital Isn’t Enough

Nothing guarantees that strong social capital can compensate for lack of social services and economic opportunity. While it’s important to highlight success stories like Lewiston or Altona, there are also incidents where refugees attempted to make a home in declining or non-urban communities and failed. These instances provide insight into the limits of using informal networks to support refugee communities and some of the difficulties refugees face in small communities.

The experiences of Hmong refugees in Missoula, Montana illustrate this. General Vang Pao led a community of 250,000 Hmong in a CIA-backed war against the communist forces of Pathet Lao in Laos. After losing the war in 1976 (and 30,000 of their 250,000-member community), the Hmong faced persecution in Laos for their alliance with the United States, and tens of thousands of Hmong fled into neighboring Thailand.

Eventually, 103,000 Hmong were resettled in the United States. While making plans to move to the U.S., Vang Pao was advised by a Montana-native friend in the CIA to move to Missoula, Montana. In the hopes that he might create a robust Hmong community in rural Montana, Pao purchased a three-story ranch house and a 400-acre farm just outside of Missoula in 1975. He came with 60 other Hmong refugees, but soon afterward, nearly 100 Hmong refugees would be arriving in Missoula every month until peaking at about 1,000 people in 1980, approximately three percent of the town’s total population.

Missoula was ill-prepared to receive a new refugee population. Refugees were left uninformed of how to use amenities such as hot water or refrigerators or practical skills such as how to pay bills. Many came to Missoula with wounds from the war, poor health, and psychological issues and were unable to receive proper treatment. There were no translators available at Missoula hospitals, nor did the doctors understand that they had a different concept of medicine and treatment, and often a distrust of doctors due to their experiences in Laos. The school district offered no bilingual education, and teachers forbade children from speaking the Hmong language in school. As a result, Hmong children had difficulty using their language and struggled to communicate with their parents, who didn’t know English.

Ultimately, Vang Pao could not create the large Hmong community in Montana he was hoping for. He and other Hmong leaders such as Moua Cha decided to leave Montana for California in search of better economic opportunities and to support the larger Hmong community growing there. In just a few years, three-quarters of the Hmong population had left Missoula. In 1980 the International Rescue Committee office, which had been established to run the Missoula resettlement program, closed, and by 1990 there were only 250 Hmong left in the city.

There are several takeaways from Missoula’s attempt to resettle Hmong refugees. While social ties were strong between the Hmong themselves, there was little bridging capital between them and the Missoula community. Policies like refusing to allow children to speak the Hmong language in school deteriorated the existing bonding capital of the Hmong because it separated children from a critical part of their culture while limiting their ability to communicate with their parents. This meant the Hmong were absent the initial social capital that they had arrived with. This shows that small communities can not solely rely on the social capital of refugees as a tool of integration; they must actively promote both bonding and bridging capital between refugees and the host community and provide the resources required for successful integration.

But this is not the end of Missoula’s history as a resettlement destination. Using a community-based resettlement model, it has since become a thriving resettlement destination. In 2015, several members of a Missoula book club were inspired to take action in the refugee crisis by the now-famous image of three-year-old Syrian refugee, Alan Kurdi, lying dead on a Turkish beach after his family tried to flee violence in Syria. This informal group of pro-refugee advocates grew outside of the book club and began to advocate for a resettlement office to reopen in Missoula.

They reached out to key stakeholders in the Missoula community, such as the Missoula County Public Schools System and laid the groundwork for refugee arrivals. They also reached out to the International Rescue Committee, which had run the resettlement program in Montana in the 1970s and 80s, to open a new office. This group of advocates became Soft Landing Missoula, a community support organization for refugee resettlement that supports the IRC in its efforts in Montana through running programs like food pantries, driver’s ed programs, and helping refugees start businesses. Most of their work involves informing the Missoula community about the resettlement program through lecture series and bridging the gap between native-born community members and refugees.

This is close to Canada’s private resettlement program in the United States; a small community lobbied to have their community become a resettlement destination and laid the groundwork for a resettlement program.

Conclusion

Ultimately, evidence from refugees in these small and declining communities challenges several of our notions of resettlement and integration. First and foremost, it calls into question our tendency to only resettle refugees in large metropolitan communities; in many of these communities, we see integration and financial well-being on par or better than what we would find in traditional resettlement destinations. Second, we see that social capital, friendship, and community bonds play a huge role in determining the success of refugees and can ultimately define whether or not their host community succeeds. And third, many of these stories challenge the perceptions of refugees as competitors rather than as additions to community resources. Refugees in small and declining communities can enhance the social capital of their new communities by bolstering (or in some cases, saving) the economy, supporting institutions like the school system, and inspiring civic engagement.

Hopefully, future research will reveal more regarding integration, social capital, and success in these communities and encourage change in designing resettlement programs and supporting secondary migrations.

WILL CLEMENTS

Will Clements is currently a Caseworker with the International Rescue Committee’s Unaccompanied Children Program. He graduated from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in 2020 and wrote his thesis on refugees in rural communities.

The author would like to thank The Hitachi Center for Technology and International Affairs for their partnership in this research. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Contact: Kimberly.wilson@tufts.edu

[1] Albrecht, Sabina, and David Smerdon. “When refugees work: The social capital effects of resettlement on host communities.” Unpublished Manuscript (2016).

[2] Albrecht & Smerdon, Page 3.

[3] Albrecht, Sabina, and David Smerdon. “When refugees work: The social capital effects of resettlement on host communities.” Unpublished Manuscript (2016).