One of the lyrics from Blue Swede’s popular 1970’s hit “Hooked on a Feeling” makes reference to being unable to stop or control one’s feelings (James, 1968). Some could argue that that statement might be true in reference to affairs of the heart, but emotion regulation researchers would probably take a different stance. As previously discussed, emotion regulation strategies such as attentional deployment and cognitive reappraisal can be used to modulate emotional responses, but what happens in certain mental illnesses where emotional dysfunction includes recurrent and intrusive negative emotions?

Anxiety disorders (especially generalized anxiety disorder; GAD) are characterized by excessive anxiety and worry to the point that it induces significant distress as well as impairment of functioning (APA, 2013). Charlie Brown from Charles Schulz’s classic comic series “Peanuts” displays many typical signs of rumination and worry seen in GAD.

Ruminative type symptoms are also seen in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) under the general header of negative alterations in cognition and mood. These symptoms include pervasive negative beliefs about oneself or the world, such as feelings of self-blame and guilt, which often coincide with distorted beliefs about the traumatic event that led to the development of PTSD (APA, 2013). Persistent depressive symptoms, such as negative emotional state (e.g. anger, shame, etc.) and inability to feel pleasure (anhedonia), as well as hyper-arousal symptoms, like exaggerated startle response and constantly feeling on edge or hyper-vigilant, are also features of PTSD symptomatology (APA, 2013). Additionally, PTSD is characterized by intrusive symptoms, defined as recurrent, involuntary, and distressing trauma-related memories; these often appear in nightmares or during flashbacks, which are powerful, involuntary episodes where a memory is re-experienced (APA, 2013). This profile of symptoms often leads to diminished interest in or participation in normal activities and result in social isolation (APA, 2013). These symptoms are also associated with significant distress and may increase maladaptive emotion regulation, such as negative appraisal and avoidance (detailed in a previous post).

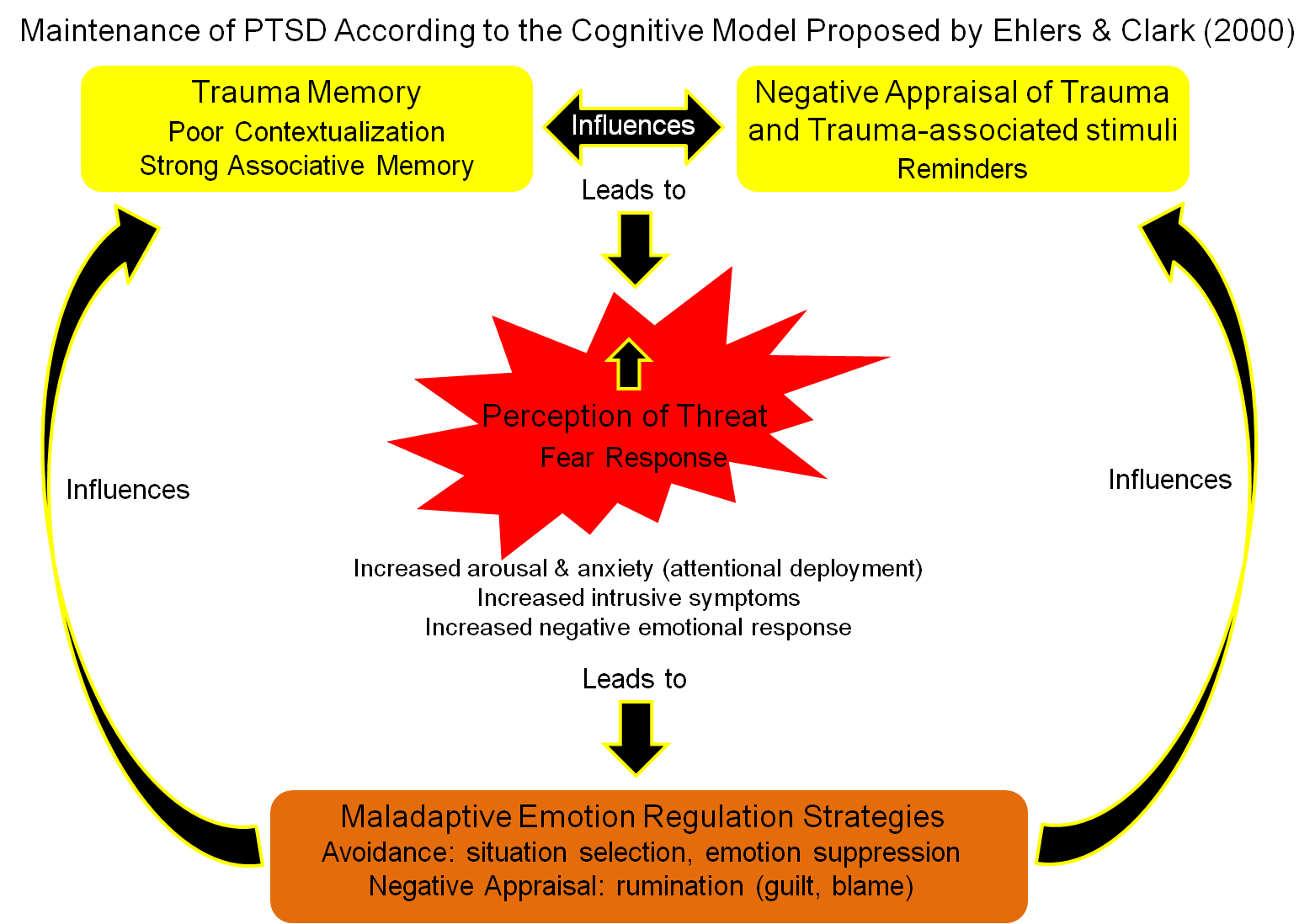

Ehlers and Clark (2000) created a cognitive model of PTSD, in which symptoms are modulated and maintained by maladaptive emotion regulation. They proposed that the clinical presentation of PTSD is a heightened sense of threat or fear that is perpetuated by 1) negative appraisal of the trauma including trauma-associated stimuli (reminders) and 2) memory disturbances regarding the trauma including poor contextualization of the event and strong associative memory. These two factors influence each other and prime an individual for increased perception of threat (attentional deployment towards threat), which leads to increased fear-response comprised of heightened arousal and anxiety, increased intrusive symptoms, and increased negative emotional response. In response to this emotional assault, an individual will employ maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. Avoidance strategies include avoiding reminders of the trauma (situation selection to avoid people and places associated with the event) as well as emotional suppression or numbing; this leads to increased social isolation. Negative appraisal strategies include rumination with feelings of guilt and self-blame. This maladaptive emotion regulation forms a feedback loop to further influence the perception of the trauma and exacerbate the symptoms of PTSD.

Watkins (2008) expanded on the role of rumination in the cognitive model of PTSD. According to his theory, rumination or repetitive thinking can be employed unconstructively, increasing symptoms of anxiety and depression as proposed in Ehlers and Clark’s model (2000), but that rumination can also be utilized constructively to help people process their traumatic experiences and work towards healing (Watkins, 2008). Based largely on work by Susan Nolen-Hoeksema indicating that rumination predicts certain symptoms of depression and anxiety (reviewed in Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000), Watkins (2008) proposed that the best determinant for whether or not rumination will be constructive or unconstructive is the type of processing used during rumination. Concrete (experiential) processing involves focusing on the experience of feelings and mood during ruminative thoughts whereas abstract (evaluative) processing involves thinking about causes, meanings, and consequences of ruminative thoughts. In constructive rumination during a symptom provocation paradigm, abstract (evaluative) processing has been shown to decrease PTSD-related intrusive symptoms more than concrete (experiential) processing (Santa Maria et al., 2012).

The brain regions involved in rumination were recently examined in a structural brain imaging study. Qiao and colleagues (2013) assessed sensitivity to trauma (measured as negative life events) in healthy adolescents, and found that larger grey matter brain volume in the left inferior frontal gyrus positively correlated with increased sensitivity to trauma. Additionally, increased rumination was associated with larger grey matter volume in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC). Further analyses indicated that rumination and the VLPFC mediated the effect of sensitivity to trauma. The authors suggested that increased brain volume in the VLPFC may be related to an inclination towards increased rumination, which could lead to increased sensitivity to trauma.

Now that we’ve ruminated on this topic for a while (I know, I’m awful), my next blog entry will tie all of my previously discussed points together in a review of treatment options for PTSD that utilize emotion regulation strategies. Spoiler alert! The basic premise is to replace maladaptive strategies with more adaptive strategies, or as my grandmother liked to say, “Find a way to turn that frown upside-down!”

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 319-345.

James, M. (1968). Hooked on a Feeling [Recorded by Blue Swede]. On Hooked on a Feeling [LP]. EMI Svenska. (Released 1974).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504-11.

Santa Maria, A., Reichert, F., Hummel, S. B., & Ehring, T. (2012). Effects of rumination on intrusive memories: does processing mode matter?, Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43, 901-9.

Qiao, L., Wei, D. T., Li, W. F., Chen, Q. L., Che, X. W., Li, B. B., Li, Y. D., Qiu, J., Zhang, Q. L., & Liu, Y. J. (2013). Rumination mediates the relationship between structural variations in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and sensitivity to negative life events, Neuroscience, 255, 255-264.

Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought, Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163-206.