By: Magali Ortiz

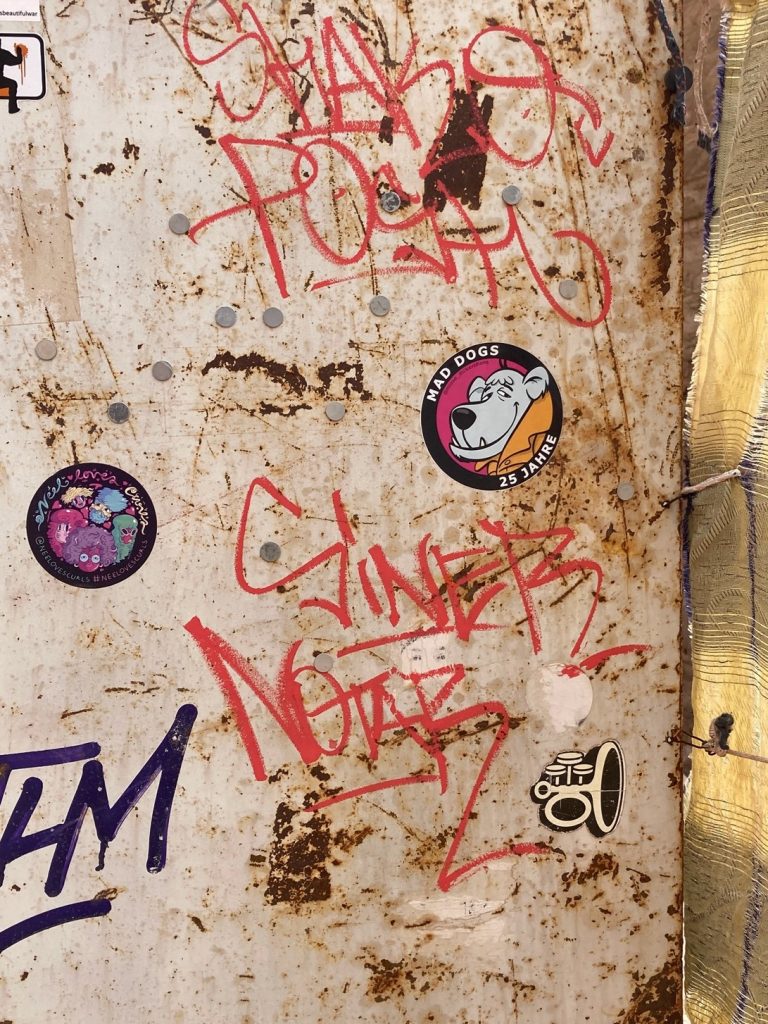

After a week of researching street art in Amman, my eyes are constantly on the lookout for graffiti and murals. So when our group embarks on a road trip to Wadi Rum and Petra, it’s impossible not to notice the stray graffiti here and there on the side of the road. Even as we get into remote stretches of desert, the occasional structure that pops up is almost always tagged, marked by someone’s spray can. Only once do I see graffiti at the base of a rocky mountain. I add a note to my mental list of the unwritten rules of graffitiing: don’t vandalize natural structures. This proves true in Petra, where street artists have repeatedly tagged the little shops and stands that dot the long hike through the wind-chiseled rocks, but not the rocks themselves, which are already streaked with color. Near the top, just a few minutes from the monastery, I have to laugh when I see a tag by an artist I recognize – SINER, one of the most prolific graffiti artists in Amman. Of course he would bring a spray can to Petra.

It’s a fun game to play – once you know a street artist’s signature, you start spotting it everywhere. As we drive back into the city Saturday afternoon, I point out a piece by MIG overlooking the highway. He’s someone the whole group has learned to spot, not only because of his style and signature robot, but because he’s literally everywhere in Amman. When I interviewed him earlier in the week, he showed me his Google Maps app, where he marks every potential spot for his art. The screen is so covered with blue markers that in some places it’s difficult to make out the map underneath.

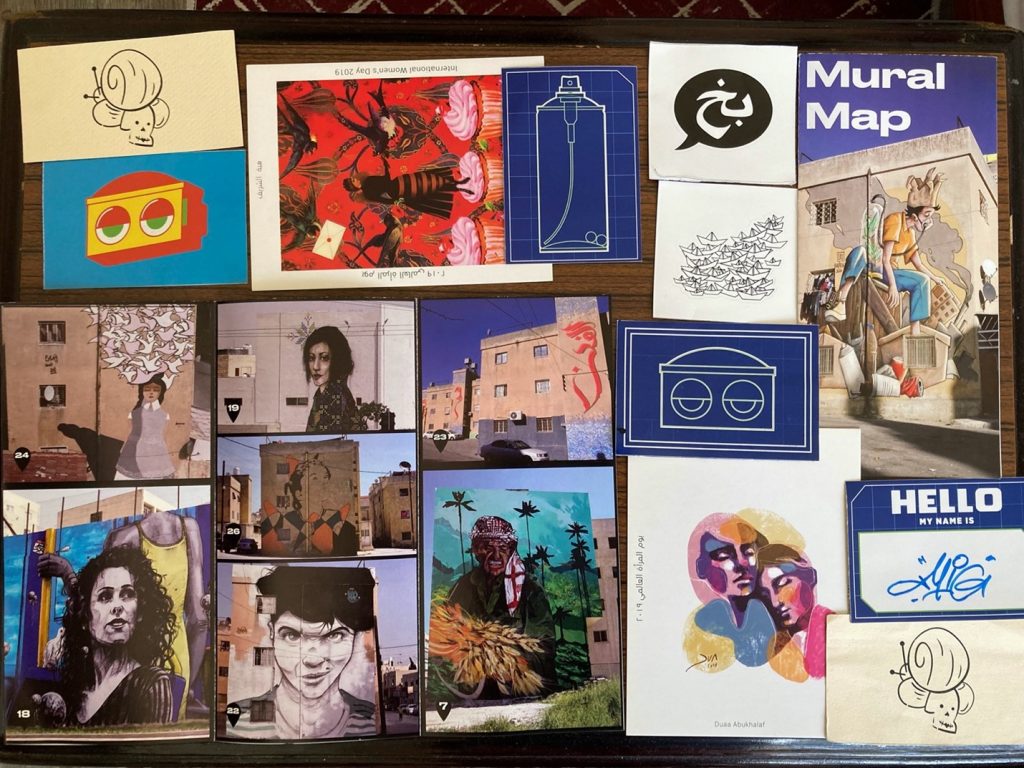

Saturday evening, when I discuss the city’s street art with Sardine, he uses MIG as an example of how dedicated some street artists can be. Sardine, AKA Mike Derderian, has been in the graffiti game for a long time. We’ve been trying to find a time to meet since I landed in Amman, but it wasn’t until his art show that our schedules managed to line up. The show is hosted at F.A.D.A.317, Sardine’s studio and the only one in the city dedicated to street artists. Although he still goes out to spray paint frequently – Sardine’s characters can be seen all over the city – he has started to focus more on other art forms, such as his short film Geisha L.O.V.E., which debuts that evening. Nevertheless, he still knows everyone involved in Amman’s small but constantly growing street art scene. His show features collaborations with a variety of local artists, and during our talk in his office, he constantly mentions muralists and graffiti artists, often pointing out their art on his walls. Afterwards, when we venture back out into the art show, he introduces me to other artists, some that I’ve met, others that I only recognize from their art that I’ve seen walking around the city. Naji AlAli is yet another of the truly dedicated – his lemonheads can be seen all over, including at the entrance to F.A.D.A.317.

Walking back to our hotel from the studio through Al-Weibdeh and Wasat Al-Balad, street art adorns most of the walls that I pass. Some of it is the casual, fast work of artists like SINER or MIG, some are small murals done by the likes of Sardine or Yaratun, or bigger street art crews. On one busy street, you can find a host of murals by renown artists like Suhaib Attar, done during different years of Baladk, an annual street art festival hosted by Amman’s Al-Balad theater. Somehow, it has become second nature to recognize styles, signatures, tags. It’s my last evening in the city, and I’ve only been here a short while, but I feel a deep sense of familiarity with its walls. After all my conversations with artists about the future of Amman’s street art, I wonder what the city will look like on my next visit, and how the medium will continue to take hold in other cities like Irbid and Petra, as well as all the long highways in between.