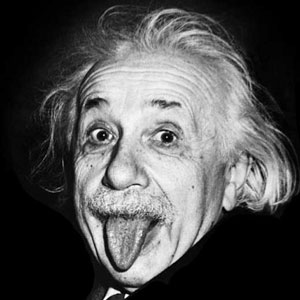

“We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Sahara. Certainly, those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively exceeds the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here. We privileged few, who won the lottery of birth against all odds, how dare we whine at our inevitable return to that prior state from which the vast majority have never stirred?”

-Richard Dawkins, Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder

This powerful passage signs off a wonderfully unique song by the Finnish symphonic metal band Nightwish from their album Endless Forms Most Beautiful. Drawing on works from Charles Darwin and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins (who’s book The Greatest Show on Earth inspired the song name), this 24-minute magnum opus explores the major events of life’s evolutionary history to present day. The song is broken up into four larger parts that tell the tale of Earth’s unique history. This has quickly become one of my favorite songs. Let’s now take a closer look at how Nightwish set out to marry heavy metal with evolutionary biology concepts (link to a live version with guest appearance by Dawkins will appear at the end of this article).

Part 1: Four Point Six

The song opens with a repetitive and fluid piano melody accompanied by orchestral components that signify whatever “existed” before the Big Bang . At 1:33 the Big Bang arrives, and the music shifts to convey the resulting chaos and energy of a nascent universe being born. At 1:55 we are introduced to the main melodic theme that we will revisit throughout the song. Several more explosions are heard (2:40) which I imagine as our solar system coming together from the ensuing bombardment. The first lyrics are sung as a haunting ephemeral wailing.

Archaean horizon, The first sunrise

On a pristine Gaea

Opus perfectum, somewhere there, us sleeping

Geologic time is broken into distinct eons, and the Archaean signified the earliest emergence of life. In Greek mythology, this life arose from Gaea the Greek goddess of the Earth. Life has now been established (opus perfectum- “perfect work”) and eventually mankind will appear from this starting template billions of years later. We are reminded that all the elemental building blocks are present in this early Earth, “waiting” to be reorganized into the human species. Next is another Dawkin’s excerpt:

“After sleeping through a hundred million centuries

We have finally opened our eyes on a sumptuous planet

Sparkling with color, bountiful with life

Within decades we must close our eyes again

Isn’t it a noble, an enlightened way of spending our brief

Time in the sun, to work at understanding the universe

And how we have come to wake up in it?”

The song then erupts into fanfare (5:46), life is here and begins its unending 3-billion-year journey.

Part 2: Life

The cosmic law of gravity

Pulled the newborns around a fire,

A careless cold infinity

in every vast direction

Lonely farer in the Goldilocks zone

She has a tale to tell

From the stellar nursery into a carbon feast

Enter LUCA

Here is the birth of our solar system with Earth becoming one of the nascent planets circling our Sun. Outside the solar system, there is a vast and cold emptiness for light years in all directions. Earth is the lucky one in the Goldilocks zone (not too hot, nor too cold, but just right). The early Earth contains all the building blocks leading to the eventual evolution of our Last Universal Common Ancestor from which all current life sprang.

The tapestry of chemistry

There’s a writing in the garden

Leading us to the mother of all

In my mind tapestries evoke “weaving” which makes me think of the endless strands of double helical DNA connecting all forms of life through history. Life is commonly referred to as a garden and this can be interpreted as reading the fossil record showing us snapshots of the interconnectedness of all life in the past.

We are one,

We are a universe

Forebears of what will be Scions of the Devonian sea.

Aeons pass, writing the tale of us all

A day-to-day new opening

for the greatest show on Earth

Naturally what follows is that all life is connected as one. The band highlights the Devonian era which was a time period of massive radiation of fish (this era is termed The Age of Fishes) as well as land colonization of plants. We are all scions, descendants of a notable family (family tree of life), from this time period. Looking back even earlier to the Cambrian explosion, the earliest known chordate, Pikaia, is the ancestor to all vertebrates. We now roll credits for the mention of the song’s title. Since life is always changing and evolving, each day is different. Thus, the story of life has a day-to-day new opening.

Ion channels

welcoming the outside world to the stuff of stars

Bedding the tree of a biological holy,

Enter life

There is a reference here to Carl Sagan who coined the term “starstuff” referring to all of life being made up of elements formed from the dying explosions of exhausted stars. Another beautiful connectedness of all life, arising not only from a common ancestor, but incorporating all matter born in the belly of long-gone stars. The focus on ion channels here is striking when you think about what they are trying to convey. Elements from dead stars were eventually combined into living forms that evolved proteins capable of generating action potentials in our neurons which allowed ourselves to become aware of the universe. Essentially through ion channels, the universe is able to learn about itself.

We are here to care for the garden

The wonder of birth of every formmost beautiful

Every form most beautiful

Chronologically humans have not appeared yet in the history of life, nor the song. I am unsure of the “we” that is referred to here, but it could be the general responsibility of all life due to our connectedness. Of course all lifeforms are beautiful, an homage to the final sentences of Darwin’s Origin of Species.

Part 3: The Toolmaker

Humankind has arrived. Animal grunts and other savannah creatures can be heard during our early days of trying to survive amongst animals that could easily kill us. The song explodes into another heavy riff signifying our eventual dominance over all life on Earth (11:53).

After a billion years

The show is still here

Not a single one of your fathers died young

The handy travelers out of Africa

Little Lucy of the Afar

This stanza makes us remember that we are all here because each one of our ancestors going back billions of years successfully reproduced itself to the next generation. An unyielding unbroken chain avoided life’s dead ends of extinct genera and species. We know that early humans migrated out of Africa and the earliest known mother of humankind was an Australopithecine named Lucy found in eastern Africa.

Gave birth to fantasy

To idolatry

To self-destructive weaponry

Enter the god of gaps

Deep within the past

Atavistic dread of the hunted

As the human brain developed it gave rise to religion and mythology to fill in gaps of missing knowledge, attributing that which was not known to deities. We also strive for continual and never-ending progress, as atavism is the fear of returning to a more primitive ancestral state (how could any of us live without the Internet?!)

Enter Ionia

The cradle of thought

The architecture of understanding

The human lust to feel so exceptional

To rule the Earth

Man has settled into civilizations and frees up time to think and discover how the world works. We elevate our status as greater than all other life forms, set to inherit the Earth.

Hunger for shiny rocks

For giant mushroom clouds

The will to do just as you’d be done by

Here is the self-explanatory human lust for gold and money, but also dominance over other humans through creation of super weapons. Weapons that have the capability of destroying ourselves.

Enter history

The grand finale

Enter ratkind

A warning of what may come. A reference to another Dawkin’s work, The Ancestor’s Tale. Here Dawkins imagines a post-apocalyptic world where rats survive and feast on the remains of human corpses and our agriculture/food products. As the population of rats explodes, they resort to cannibalism. Natural selection, always running in the background, allows rats to diverge and radiate out into different carnivorous and herbivorous species. Eventually through enough geologic time, intelligence arises in one species to that of humans. They then study human fossils and ponder how we had driven ourselves extinct.

Man, he took his time in the sun

Had a dream to understand

A single grain of sand

He gave birth to poetry

But one day’ll cease to be

Greet the last light of the library

I especially appreciate this passage as all scientists can relate to devoting our life’s work to a very small esoteric topic. Each of us has or could have their own “grain of sand” that they seek to fully understand. This is a unique attribute of human beings, but this facet of life may not always exist forever, ending with the destruction of the human race.

There is a notable section highlighting the evolution of humans through that of our music (starting at 13:55). Early tribal drumming and chanting can be heard. This is followed by throat singing and a famous Bach snippet. A rocket blast sets off the Modern Age and a banjo depicting country music. Then the unmistakable main riff from Enter Sandman by Metallica can be heard followed by a short measure of techno or electronic music.

Finally, the climax of the song. A desperate loud exclamation, “We were here!” emphasizes the desire that all humans have the need to be remembered, to leave their mark. I see this section as a warning as well. This proclamation ends with an explosion and crumbling rock. If continued on its current path, human society will be been destroyed. “We were here!” is an audible fossil to record how the human race once evolved to dominate the planet but like countless species before it, has gone extinct.

Part 4: The Understanding

Another gentle piano melody appears and allows us to reflect and take in the previous 17 minutes. We did just play out the entire history of life on Earth after all.

The song ends with the passage from The Greatest Show on Earth that began this article, and then the closing excerpt from Origin of Species.

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one. And that whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

I hope you enjoy the song as much as I do. It has quickly become one of my favorite songs, combining my love of biology, the works of Dawkins and Darwin, and metal music. Check out a live version with guest appearance by Richard Dawkins below: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qrMwxe2ya5E&ab_channel=Nightwish