Refuge?: Refugees’ Stories of Rebuilding their Lives in Kenya

In this issue of Fresh FINDings, we are excited to share our newest report titled Refuge? Refugees’ Stories of Rebuilding their Lives in Kenya

Please visit the Journeys Project at Tufts University for previous studies, ongoing research, videos, maps, and artwork on refugees and migrants in the Middle East and Mediterranean, Latin America, and Africa.

This month…

- Refuge?: Refugees’ Stories of Rebuilding their Lives in Kenya

Refuge?: Refugee’s Stories of Rebuilding their Lives in Kenya

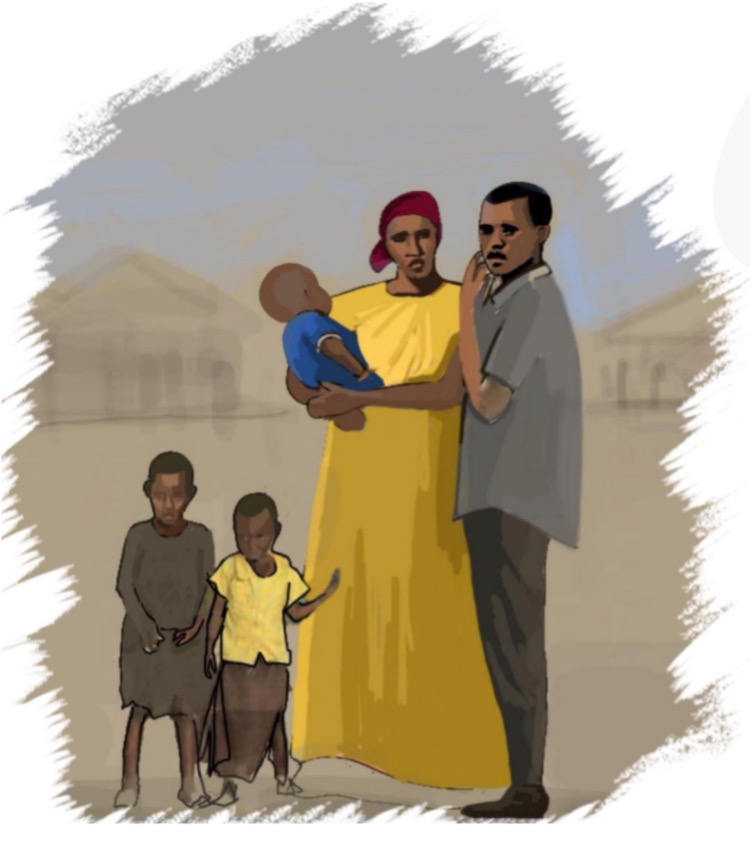

We are thrilled to announce the launch of Refuge? Edited by Sophie Gitonga, Ray Mwihaki, Julie Zollmann, and Kim Wilson. Illustrated by Liyou Zewide.

This new collection pulls together refugees’ own stories of flight and resilience in Kenya. Through their reflections, we see the disorientation of displacement, the hope that many find in Kenya, particularly through education, and the many barriers people face trying to work and build a full economic life in a country that is never quite home, even when one has been living there for many years, or even born inside a refugee camp .

As of January 2021, more than half a million refugees were living in Kenya, forced from their homes by political violence and its aftermath in Somalia, South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi. While Kenya has hosted refugees since its independence, larger flows began in the 1980s, and by the 1990s, the government had begun restricting refugees’ socio-economic freedoms. By 2014, the government had made it a criminal offense for refugees to travel outside of Kakuma and Dadaab refugee camps without permission. Refugees are routinely harassed for their documents, often as they wait for very long periods for those documents to be processed or renewed by Kenyan authorities. While on paper, refugees have the right to work, in practice, work permits are issued extremely sparingly. Even refugees’ ability to use banking infrastructure and M-Pesa have been curtailed in punitive reactions to terror attacks, which the government blames on its refugee population. In late 2019, the President signed a new Refugee Acti into law, raising hope for a new era of inclusive refugee practices, including greater freedom to work, but the government’s

We hope this collection will be read by Kenyans and non-Kenyans alike who want to learn more about how seeking refuge in Kenya is experienced. These stories come from refugees initially hailing from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Somalia, Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi. All of these stories were written during the Covid-19 pandemic. promise to close the country’s refugee camps in the middle of 2022 makes some question the government’s commitments to the new direction outlined in the Act.

We found these narratives, 31 in total, so compelling that we decided to share them in the form of this collection. We thank the reader for your time in learning about their nightmares and their dreams.

Click here for a link to the full collection

.

Methodology: Field research during COVID-19

Collecting refugees’ own autobiographies was not part of the original FIND research plans, which were made before the Covid-19 outbreak. When Covid arrived in Kenya, the team had just finished screening potential Nairobi-based research participants and had yet to travel to other expected field sites: Eldoret, Kakuma, and Mombasa. We worried at first whether the entire project would need to be put on hold. We decided to focus our main research on the Nairobi participants we already recruited and who could be interviewed on the phone. But to get insights outside of Nairobi, where travel was restricted, we needed an even more creative adaptation.

We wondered whether it might be possible for refugees to record their own stories. We weren’t sure how that would go at first and considered this part of the project an experiment. We reached out through our networks to identify bilingual/multilingual refugees willing to work with us in our first attempt. We then had an introductory call with each of them to tell them more about the project and what we were trying to do. Most of our collaborators were young people who recently finished secondary school and were stuck moving to other transitions because of Covid. Therefore the recent graduates had both the time and the bandwidth to assist in the research. There were six research assistants in total.

We conducted one-on-one trainings over Zoom for our new researchers. While connectivity was often a challenge, usually we were able to make things work eventually in one-on-one sessions. These trainings gave us a chance to connect better and explain what we were looking for.

Our researchers began their work by going off and writing their own stories, based on a detailed guide of questions we provided. When we received their first drafts, we asked lots of follow up questions to understand their situations better and clarify points that were not clear in the first narrative. That process helped our writers understand better what we were looking for.

We then talked to the research assistants again to give feedback to us on the process and brainstorm who else they might approach to see if they wanted to have their stories written. They targeted others who spoke their same vernaculars and lived nearby. They reached out to up to four others and worked with them to help these others record their stories into English, using the same process, but this time interviewing people to write their stories. Our refugee writers documented the stories of 24 additional individuals. Again, we asked lots of questions on the drafts until things were clear and felt complete.

After this stage, two talented Kenyan writers, Ray Mwihaki and Sophie Gitonga stepped in to take each story and polish it to bring out the core themes and get the language publication-ready.

We provided thank you gifts to both the writers and the individuals they interviewed who shared their stories. We also paid for data bundles or time at internet cafes to facilitate the writers’ work.

Though different from what we had originally planned, these stories proved an insightful and rich contribution to the project.

.

Story Highlight: Still Alive

Narrated by Paul, 40, Nairobi & Mombasa

Things were good when I was a child in Rwanda. My mother remarried when I was young, so I grew up in my grandparents’ middle-class home. They had a big farm with crops and livestock. There was so much nutritious food and milk that I grew very quickly. My teachers used to even joke that with my height I could be the father of the other students.

Everything was good for me until the violence of 1994. Two of my uncles had gone to Burundi to encourage refugees there to come home. When my uncles didn’t come back home, we started to worry. Then we heard their bodies were found outside of a school near the border, on the Rwanda side. I knew I had to leave. I grabbed a 30kg bag of groundnuts from my grandparents’ storeroom to take with me, hoping I could sell them in the camp across the border in Burundi and survive for some time. I sold the groundnuts for about $5, which only lasted a few days. But then we got word that the camp was to be bombed. We found someone willing to help us cross to Tanzania, but we needed $2 each for the trip, and we didn’t have it.

A friend and I decided we would secretly cross back into Rwanda. The land near the border was fertile, and we could harvest some cassava to sell and get enough money to pay for our journey to Tanzania. It was a risky plan. This area was being patrolled 24/7 by the Rwandan military. We walked the three hours to the border and snuck across just after nightfall, around 7 pm. While we were doing our harvesting, we saw a military truck heading toward the river with the lights off. Throughout the night we heard the cries of people being attacked by the military for doing like us, harvesting from these fields close to the border. We were terrified at daybreak and hid, unsure of what to do.

Then, we started seeing others making their way back to the river with their own sacks of harvested food and decided to try our luck. As we made our way down to the river, we saw a man standing with a bloodsoaked machete and froze, terrified. He told us to hurry down to the river. We didn’t ask questions and kept running, unsure of what or whom he had killed. At the river, there were no boats, but there were fishermen on the other bank. As we surveyed the situation, we saw two men in uniforms with guns running our way. With no other choice, we jumped into the river. Fishermen were shouting, trying to coach us across: “Don’t lift your legs, just drag them in the water!” I finally reached a boat, climbed in, and hid in the hull. I was holding tightly to my harvest. It was my ticket out of the camp.

Paul’s story is one of resilience and strength. Paul survived genocide, constant displacement (as camps were bombed or he was simply forced out), avoided countless men with machetes, and even survived tuberculosis all by the age of 16. Paul began his journey to financial stability by taking care of villager’s cattle in Tanzania for only $2 a month. By 18, Paul sought to learn French and attend university so he began engaging in various side hustles to make ends meet.

You can find the rest of Paul’s Story beginning on page 25 of our book.

Fresh FINDings is made possible through a partnership among Tufts University, the Katholische Universität Eichstätt – Ingolstadt (Catholic University or KU), the International Rescue Committee and GIZ. Fresh FINDings also features work sponsored by Catholic Relief Services, Mercy Corps, and the International Organization for Migration.

Contact: Kimberley.Wilson@tufts.edu